Pope Francis and Archbishop Charles Chaput leave Independence Hall after the pope gave an address about religious liberty and immigration in Philadelphia Sept. 26, 2015. (CNS/Paul Haring)

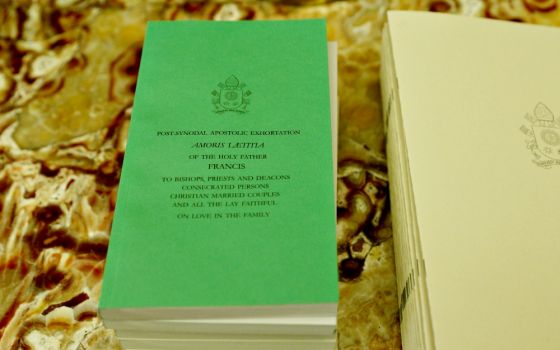

Some have called Pope Francis' Amoris Laetitia, or "The Joy of Love," his reflection on the two recent Synods of Bishops on the family, a "love letter" to families. We believe that Francis' teaching on conscience in that letter is one of the most important teachings in the apostolic exhortation. As various church bodies announced plans about how to implement Amoris Laetitia, it is instructive to see how they will present Francis' teaching on conscience.

To spread the teaching of Amoris Laetitia though U.S. dioceses and parishes, the U.S. bishops have appointed a working group led by Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput. The work of this group isn't yet public, but Chaput has issued guidelines for implementing Amoris Laetitia in his own archdiocese.

In the Philadelphia guidelines, which went into effect in July, Chaput comments on the indissolubility of marriage and admission to Communion for the divorced and remarried without an annulment. He noted that pastors have an obligation to educate the faithful, since "the subjective conscience of the individual can never be set against objective moral truth, as if conscience and truth were two competing principles for moral decision-making." The "objective truth," according to magisterial teaching, is that couples living in this situation are committing adultery and cannot receive Communion and that their subjective consciences must adhere to this truth.

Chaput's comment highlights theological debates in the Catholic tradition on the interrelationship between conscience and objective norms in moral decision-making. Some commentators on Amoris Laetitia have posited that its emphasis on conscience and inclusion of the internal forum -- which "contributes to the formation of a correct judgment [of conscience] on what hinders the possibility of a fuller participation in the life of the Church and on what steps can foster it and make it grow" -- to resolve questions of "irregular situations" in marital and other relationships have reinstituted the authority of conscience in the Catholic tradition.

Thomas Aquinas first established the authority and inviolability of conscience, which was affirmed in the Second Vatican Council's Gaudium et Spes and Dignitatis Humanae. Other commentators, like Chaput -- who does not even mention the internal forum in his archdiocesan pastoral guidelines for implementing Amoris Laetitia -- believe that subjective conscience must always submit to, and obey, the objective "truth" of magisterial teaching.

At the root of these different interpretations of the authority of conscience are distinct understandings of the interrelationship between the objective and subjective realms of morality and how they relate to conscience. Stated succinctly, is conscience subjective and internal and truth objective and external, whereby the subjective and internal conscience must obey and conform to the objective and external truth? Or does conscience include both the objective and subjective realms, whereby conscience discerns and interprets its understanding of objective truth and exercises that understanding in the subjective judgment of conscience?

'Objective' norms

Chaput's assertion on the interrelationship between the subjective conscience and objective truth reflect ongoing post-conciliar debates over the relationship between conscience and "objective" norms. German theologian Jesuit Fr. Josef Fuchs states the terms of this debate as: Does a truth exist "in itself" or "in myself"?

The first formulation sees the conscience as subjective; there is not an objective role for conscience. Objectivity is consigned to the objective norm "in itself," "external" to conscience. These objective norms exist outside the subjective conscience.

The role of the conscience is to know and apply these norms as a deductive syllogism. That is, synderesis, a property of the intellect, has an innate natural grasp of moral principles of divine law -- do good and avoid evil. These principles are formulated into objective norms, such as do not steal, do not lie, or do not receive Communion if you are divorced and remarried without an annulment.

Conscience as practical judgment knows the general principles, the objective norms that are formulated from these principles, and applies those norms in a particular situation. In this approach, conscience's freedom is relegated to obedience to external objective norms (or authority) and the dignity of conscience depends on whether or not one's judgment of conscience coincides or does not coincide with the objective norms. If it coincides with objective norms, the act is right and moral; if it does not coincide with objective norms, the act is wrong and immoral.

The second formulation sees conscience as having both the objective and subjective dimensions, what Fuchs names the subject-orientation and the object-orientation of conscience. Conscience as subject-orientation is "having inner knowledge of the moral goodness of the Christian, and as standing before God, and Christ, and in the Holy Spirit."

This is where God's voice echoes in the depths of the human heart (Gaudium et Spes, 16), "the highest norm of human life" (Dignitatis Humanae, 3), and draws a person to the absolute. There, the first principles of practical reason are self-evident in the very nature of that moral knowledge, "summoning him to love good and avoid evil" (Gaudium et Spes, 16); this is the "upright norm of one's own conscience" (Gaudium et Spes, 26).

Conscience as subject-orientation is the ontological affirmation of the intrinsic goodness of the human person created in the image and likeness of God and an invitation to enter into profound relationship with God and neighbor (Gaudium et Spes, 16).

Though conscience as subject-orientation affirms who we are, created in God's image, conscience as object-orientation "concerns the material content of the function of conscience" and indicates how we are to relate in the world. Conscience as object-orientation can "see that divine law is inscribed in the life of the earthly city" (Gaudium et Spes, 43). We respond to this world by acknowledging "the imperatives of the divine law through the mediation of conscience" (Dignitatis Humanae, 3).

Using the first principles of practical reason as a hermeneutical lens for analyzing what our relationship with the world is to be, being "guided by the objective norms of morality" (Gaudium et Spes, 16) and attending "to the sacred and certain doctrine of the Church" (Dignitatis Humanae, 14), among other sources of knowledge, conscience as objective-orientation gathers as much evidence as possible, consciously weighs and understands the evidence and its implications, and finally makes as honest a judgment as possible that this action is to be done and that action is not.

In this way, humans exercise conscience as practical judgment. Although both levels of conscience are essential, Fuchs correctly notes that the subject-orientation logically precedes the object-orientation.

In Fuchs' formulation, there is a much more complex relationship between the object-orientation of conscience and the objective norm. Since conscience can err from invincible ignorance and not lose its dignity according to Aquinas and Gaudium et Spes (16), the emphasis in Aquinas, Gaudium et Spes and Dignitatis Humanae is on the authority and dignity of conscience, not on the authority and dignity of the norm. Objective norms exist externally and are formulated and justified on the basis of the four sources of moral knowledge: Scripture, tradition, reason and experience.

These norms, however, offer nothing more than assistance -- real assistance, but nonetheless merely assistance -- in the assessment of morally correct decisions made in the conscience. External, objective norms must always go through the object-orientation of conscience where the process of understanding, judgment, decision and action take place. The object-orientation, assisted by the known principles of the subject-orientation of conscience, function as the hermeneutical lens to select, interpret and apply the appropriate objective norm in a given situation. The norms maintain their objectivity, but so too does the objectivity of the conscience.

In this formulation, truth exists "in myself," not in a relativist sense that denies objective and universal truth, but in the sense of the intrinsic human dignity of the person and the authority of conscience. Conscience must internalize the values reflected in the norm, see their relevance to the human person in all her particularity, and go through the process of understanding, judgment, decision and action.

The essential point for conscience as object-orientation is the relevance of the objective norm from the perspective of the inquiring subject in light of the understanding of all the circumstances in a particular historical cultural context. The implications of this perspective on the relationship between conscience as object-orientation and objective norms is that conscience should be guided by those norms but the authority of conscience is not identified with whether or not it obeys the objective norm. Otherwise, Dignitatis Humanae could not advocate for religious freedom, where "every man has the duty, and therefore the right, to seek the truth in matters religious in order that he may with prudence form for himself right and true [objective] judgments of conscience, under use of all suitable means."

If mere obedience to objective norms was the sole role of conscience, then conscience that leads people to follow religious traditions other than the Roman Catholic church could never be tolerated. That religious pluralism is recognized and affirmed in Dignitatis Humanae shifts authority from the objective norm to conscience as object-orientation, informed by objective norms, where the hermeneutical lens of the conscience as subject-orientation facilitates the process of understanding, judgment and decision of conscience.

Two models

Robert Smith makes a distinction between what he calls a "man-in-relationship-to-law" model of conscience and a "restless-heart-toward-God" model. He offers as exemplars of these two models Germain Grisez (and, we add, Chaput) and Bernhard Häring respectively.

Grisez holds that the only way to form one's conscience is to conform it to the teaching of the church. Ultimately, though Grisez waxes about human freedom, conscience is about obedience to church teaching and its objective norms.

Pope John Paul II's apostolic exhortation Familiaris Consortio follows this same model, being wholly rooted in both the truth of sexuality and marriage as taught by the church and the obligation of the laity to obey that truth. Almost nowhere in the document does the church's teaching on the inviolable primacy of individual conscience, even in sexual matters, appear. Such an absence unjustly ignores the long-standing Catholic tradition fundamentally strengthened at the Second Vatican Council.

Häring has a diametrically opposed stance. In the context of his overall approach to moral theology, namely, God's call to all women and men and each person's response of a moral life, conscience must be free and inviolable, and "the church must affirm the freedom of conscience itself." Church doctrine is at the service of women and men in their sincere conscience search for goodness, truth and Christian wholeness; conscience is not at the service of doctrine.

Pope Francis puts the same judgment even more forcefully in Amoris Laetitia: The Church is called, he writes, "to form consciences, not to replace them."

Francis on conscience

In Evangelii Gaudium and Amoris Laetitia, Francis brings to the fore again the Catholic doctrine on the authority and inviolability of personal conscience, especially as it relates to "irregular situations." Although Francis clearly rejects relativism and affirms objective norms (Evangelii Gaudium, 64), he warns that "realities are more important than ideas."

There has to be an ongoing dialectic between reality and ideas, "lest ideas become detached from realities … objectives more ideal than real … ethical systems bereft of kindness, intellectual discourse bereft of wisdom" (Evangelii Gaudium, 231).

Sociological surveys repeatedly affirm the vast disconnect between the objective norms of the magisterium on sexual ethics -- the absolute norms that prohibit artificial contraception, homosexual acts, and Communion for the divorced and remarried without annulment, for example -- and the perspectives of the Catholic faithful. According to these surveys, the majority of educated Catholics judge these norms are detached from reality, and Catholics are following their consciences to make practical judgments on these and other moral matters.

Francis calls for "harmonious objectivity" where ideas "are at the service of communication, understanding, and praxis" (Evangelii Gaudium, 232). Such objectivity can be found in the conscience, even in the consciences of atheists.

In his exchange with an Italian journalist on the issue of atheists, Francis commented, "The question for those who do not believe in God is to abide by their own conscience. There is sin, also for those who have no faith, in going against one's conscience. Listening to it and abiding by it means making up one's mind about what is good and evil."

The "making up one's mind" is, we maintain, not an endorsement of relativism, which Francis clearly rejects, but an affirmation of objective truth that recognizes plural and partial truths that must be discerned by conscience informed by, among other sources, external, objective norms. Francis' June 2013 statement on conscience seems to affirm our assessment:

So we also [like Jesus] must learn to listen more to our conscience. Be careful, however: this does not mean we ought to follow our ego, do whatever interests us, whatever suits us, whatever pleases us. That is not conscience. Conscience is the interior space in which we can listen to and hear the truth, the good, the voice of God. It is the inner place of our relationship with him, who speaks to our heart and helps us to discern, to understand the path we ought to take, and once the decision is made, to move forward, to remain faithful.

This statement reflects a very different model of conscience than that of Francis' two predecessors. Francis' model is much more in line with Häring's "restless-heart-toward-God" model than Grisez's (and Chaput's) "man-in-relationship-to-law" model and strikes us as more faithful to the long-established Catholic tradition and its teaching on the inviolability of conscience.

In Amoris Laetitia, Francis brings squarely to the moral forefront again the ancient Catholic teaching on the authority and inviolability of personal conscience. Indeed, his teaching there on conscience is, in our opinion, one of the most important teachings in the exhortation. He judges that "individual conscience needs to be better incorporated into the church's praxis in certain situations which do not objectively embody our understanding of marriage" (Amoris Laetitia, 303).

He quotes Aquinas frequently throughout the document and especially his teaching that the more we descend into the details of irregular situations, the more general principles will be found to fail (Amoris Laetitia, 304). As the popular saying goes, the devil is in the details.

There is an "immense variety of concrete situations" and situations can be so vastly different that his document, the pope confesses, cannot "provide a new set of rules, canonical in nature and applicable to all cases" (Amoris Laetitia, 300). The only moral solution to any and every situation is a path of careful discernment accompanied by a priest and a final judgment of personal conscience that commands us to do this or not to do that (Amoris Laetitia, 300-305). Only such an informed conscience can make a moral judgment about the details of any and every particular situation.

This model of conscience, affirmed by tradition and Amoris Laetitia, provides a faithful and merciful guide for couples who are in irregular situations and empowers them to follow their inviolable conscience on this important issue, despite Chaput's statements to the contrary.

[Todd A. Salzman is a professor of theology at Creighton University. Michael G. Lawler is the emeritus Amelia and Emil Graff Professor of Catholic Theology at Creighton. They are the co-authors of The Sexual Person (Georgetown University Press).]