Three months after the publication of Pope Francis' exhortation on marriage and family, bishops and bishops' conferences around the world are studying practical ways to apply it. Some still disagree on what exactly the pope meant.

In the first week of July, Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput's pastoral guidelines for implementing the exhortation's teaching in his archdiocese went into effect; an Italian blog published reflections on the document by Cardinal Ennio Antonelli, former president of the Pontifical Council for the Family; and La Civilta Cattolica, an Italian Jesuit journal, released a long interview with Cardinal Christoph Schonborn of Vienna, the theologian the pope chose to present the document to the press.

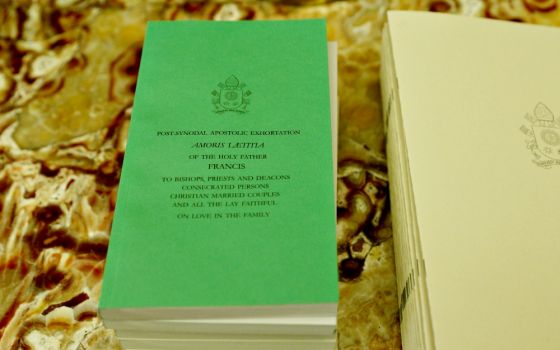

Francis continually insists that the exhortation, Amoris Laetitia ("The Joy of Love"), is about the importance and beauty of marriage and family life and the church's obligation to support and strengthen it. But much of the debate has focused on access to the sacraments for couples in what the Catholic church traditionally defined as "irregular situations," particularly people who were divorced and civilly remarried without an annulment.

Emphasizing Jesus' own words about the indissolubility of marriage and centuries of church practice, Chaput of Philadelphia urged pastors to accompany such couples, but insisted "church teaching requires them to refrain from sexual intimacy."

"Undertaking to live as brother and sister is necessary for the divorced and civilly remarried to receive reconciliation in the sacrament of penance, which could then open the way to the Eucharist," said the guidelines issued by Chaput, who was a member of the 2015 Synod of Bishops on the family and is chairman of the U.S. bishops' ad hoc committee on implementing Amoris Laetitia.

Pastors, the archbishop said, have an obligation to educate Catholics because "the subjective conscience of the individual can never be set against objective moral truth, as if conscience and truth were two competing principles for moral decision-making."

Antonelli, in the text published by the Italian journalist Sandro Magister, said the objective truth taught by Francis is what the church always has taught. "It is held in the background, however, as a presupposition. In the foreground is placed the individual moral subject with his conscience, with his interior dispositions, with his personal responsibility," which "is why it is not possible to formulate general regulations."

In an age when Christianity was dominant, the Italian cardinal said, the focus was on objective truth: Is this person living according to church teaching or not? "Anyone who fell short of the observance of the norms was presumed to be gravely culpable" and excluded from the Christian community.

However, he said, because the influence of Christianity is waning "it can be hypothesized that some persons live in objectively disordered situations without full subjective responsibility." That is why, he said, St. John Paul II believed it was "appropriate to encourage the divorced and remarried to participate more fully in the life of the church," although without access to the Eucharist.

"Pope Francis, in a cultural context of even more advanced secularization and pansexualism, is going even further, but along the same lines," the cardinal wrote. "Without being silent on the objective truth, he is concentrating his attention on subjective responsibility, which at times can be diminished or eliminated."

"The pope is therefore opening an outlet even for admission to sacramental reconciliation and eucharistic Communion," Antonelli wrote.

Such an approach brings risks, including a mistaken view that the church is accepting divorce and remarriage, he said, so he asked Francis for more explicit, "more authoritative guidelines."

La Civilta Cattolica, which is reviewed before publication by the Vatican Secretariat of State, did a lengthy interview with Schonborn, touching many of the same questions. The journal gave a copy of the interview to Catholic News Service before publication.

"It is possible, in certain cases, that the one who is in an objective situation of sin can receive the help of the sacraments," said the cardinal, a theologian who was the main editor of the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

Distinctly Catholic: Cardinal Schonborn on 'Amoris Laetitia' (July 7, 2016)

But the Austrian cardinal said Francis insisted Communion for the divorced and remarried was not a central question, which is why the pope put his response in a footnote in Amoris Laetitia.

The basic questions are: Who is in need of God's mercy and how does that mercy reach people, he said. The answer is that all people "are called to beg for mercy, to desire conversion."

No one has "a right to receive the Eucharist in an objective situation of sin," the cardinal said, which is why the pope does not grant a blanket permission and insists that civilly remarried people go through a whole process of discernment and repentance under the guidance of a priest.

Referring to the exhortation by its initials, Schonborn said, "AL is the great text of moral theology that we have been waiting for since the days of the (Second Vatican) Council and that develops further the choices that were already made by the Catechism of the Catholic Church and by 'Veritatis Splendor,'" St. John Paul's 1993 encyclical on the church's moral teaching.

The discernment called for by Francis, he said, "takes greater account of those elements that suppress or attenuate imputability" and seeks a path that would move a person closer to the fullness of what the Gospel demands.

Although not yet meeting the "objective ideal," helping a person move closer to perfection "is no small thing in the eyes of the Good Shepherd," the cardinal said.