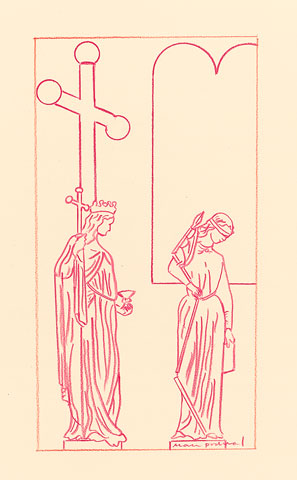

Mark Podwal. "Ecclesia and Synagoga." From the Terezin Portfolio. (Courtesy of the artist)

Many of Mark Podwal's artworks wear their Jewish identities on their sleeves. Here, an ostrich wraps itself in a tallit, or Jewish prayer shawl. There, a winged menorah dances among musical notes. A Passover image shows an Egyptian pyramid made of matzo; another crafts a city's wall of tefillin, or phylacteries. A spice box, used for the havdalah service bidding farewell to the Sabbath, contains skeletons that allude to the sack of Zion in the book of Lamentations.

And yet, on the morning of Aug. 22, just before 10 a.m. Vatican time, Podwal delivered his new Terezin Portfolio, a series on the history of anti-Semitism, to the library of the Pontifical Urban University in Rome. It sounds like the beginning of a joke -- Why did the quintessential Jewish artist cross St. Peter's Square? -- but the series is dead serious.

In one of the 42 prints in the series, a figure representing the church (Ecclesia) holds a cross and wears a crown, as the synagogue (Synagoga) stands blindfolded and hunched over nearby, bearing a broken lance. The stand-in for Jews and Judaism doesn't have her eyes covered to demonstrate her fairness and moral compass, as with Justice; the symbolism clearly depicts her as blinded to the truth of Christianity.

Podwal draws the two and adds the inscription (in Hebrew) from Psalms 119:78: "Let sinners be shamed, for they falsely accused me."

A shadow cast by an angel's wings rests on a Jewish ghetto in another image, which features the text from Psalms 91:11, "For He will assign His angel upon you, to guard you in all your goings."

The image recalls what the late Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel, who was Podwal's close friend, wrote in the foreword to Podwal's 2016 book Reimagined: 45 Years of Jewish Art: "Such is the power of this artist: he captures what death has forgotten to take."

Podwal's artistic vision layers witty juxtapositions of Jewish ritual objects and symbols upon deep historical and theological research. So careful is the artist's attention to detail that in a film he was involved in, which discusses Judaism in Prague, the lyrics to the opening song correspond to an inscription on the synagogue's facade. A work in the Terezin Portfolio about the First Crusade only depicts weapons that were available at the time.

"I'm compulsive about avoiding errors and providing accuracy even in the details of my drawings," said Podwal, a practicing dermatologist in New York, who has illustrated several of Wiesel's books.

"Elie would say that I was his best researcher," Podwal said. "Perhaps my training as a physician has contributed to my research mania. As a physician, I believe in science. Yet, as an artist, I believe in legends."

Podwal began the Terezin Portfolio following a conversation in August 2014 with Norman Patz, a rabbi involved with the Jewish community in Prague, which Podwal visits regularly. The latter asked Podwal if he wanted to have an exhibition at the Terezin Ghetto Museum in the Czech Republic, and Podwal responded enthusiastically. He decided it was most appropriate to create a series on the history of anti-Semitism, and the ways that paved the way for the Nazi's Final Solution.

"There was no need for me to create a series of only Holocaust images," he said. "Terezin possessed thousands of those by children who were inmates and [by] professional artists imprisoned there." The Nazis allowed some cultural life in Theresienstadt concentration camp, which they used as a propaganda tool to show visiting Red Cross representatives, whom they sought to convince that Jews were well-cared-for in the camps.

Hand-delivering a copy of the Terezin Portfolio to the Vatican made a special impression on Podwal, who has given editions of the series to universities and museums both in the U.S. and internationally. "Many of the images in the Terezin Portfolio depict subjects in which the church participated," Podwal said.

He cited the anti-Semitic iconography of the sculpted Ecclesia and Synagoga on the façades of cathedrals, the massacres of Jews during the crusades, the identifiable clothes Jews had to wear, and the Inquisition.

"It was utterly remarkable to me that the Vatican would acquire a portfolio of artworks which reveals how the church's centuries-old involvement in the persecutions and massacres of Jews helped create a European environment that helped lay the groundwork for the Holocaust," Podwal said.

He has tried to deliver personally the 51 (of a run of 60) numbered portfolios, so that he can discuss the works with the receiving institution. (Among the institutions, which purchased the works with donated funds, are Oxford's Bodleian Library; the British Library; Washington's Library of Congress and U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum; Israel's National Library, Hebrew University and Yad Vashem; and New York's Temple Emanu-El.)*

The director of Munich's Bavarian State Library, although on vacation, attended the presentation and said at a press conference that the "library collects for eternity, and that in Munich, the heart of Nazi Germany, the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek is honored to own Mark Podwal's Terezin Portfolio as a small reminder of what the Germans did to the Jewish people," Podwal said. "I still become emotional recalling his words."

In his remarks in Munich, Podwal quoted German philosopher Theodor Adorno, who he said is often misquoted as saying, "Writing poetry is impossible after Auschwitz."

Adorno really said "barbaric," not impossible, Podwal said. "I added that I too would like to misquote Adorno and say, 'Anti-Semitism is impossible after Auschwitz.' Tragically, anti-Semitism after Auschwitz is not only possible but in some nations flourishing."

In Rome, Podwal thought the Pontifical Urban University, which the Vatican acquisition committee had selected to receive the portfolio due to its involvement in interfaith dialogue, was located near the Spanish Steps. But it had in fact moved in the early 20th century just east of Vatican City. "We had remarkable views overlooking St. Peter's," Podwal said.

However picturesque the view, things look dire to Podwal elsewhere in Europe and even on U.S. campuses, where anti-Semitism is on the rise.

"From what I've witnessed, U.S. students barely know their own American history -- let alone the history of Israel and the Middle East, nor the history of the Jewish people," Podwal said. "My art tends to be narrative. I'm interested in transmitting stories which interest me and which I am passionate about, and which I feel need be told."

He quotes the popular Hebrew expression, l'dor va'dor, which means from generation to generation. "Essential to Judaism is passing traditions l'dor va'dor," Podwal said.

He's not worried about Catholic anti-Semitism today, but he has concerns about parts of Europe, where "it's as if the anti-Semitism of the Middle Ages continues to survive."

"Some anti-Semitism," he cautioned, "is camouflaged as anti-Zionism."

The last piece in the series, "A Song," shows the Israeli flag with the Hebrew inscription from Psalms 126:5, "The tearful sowers will harvest gladly." A golden menorah, the emblem of the state of Israel and based upon the candelabrum in the tabernacle and the temples, is adorned by fruits associated with Israel in the Bible. This particular Psalm was considered for Israel's national anthem, Podwal noted.

[Menachem Wecker is co-author of the book Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education.]

*This article was updated to clarify that the works were not donated by the artist, but purchased by the institutions with donated funds.