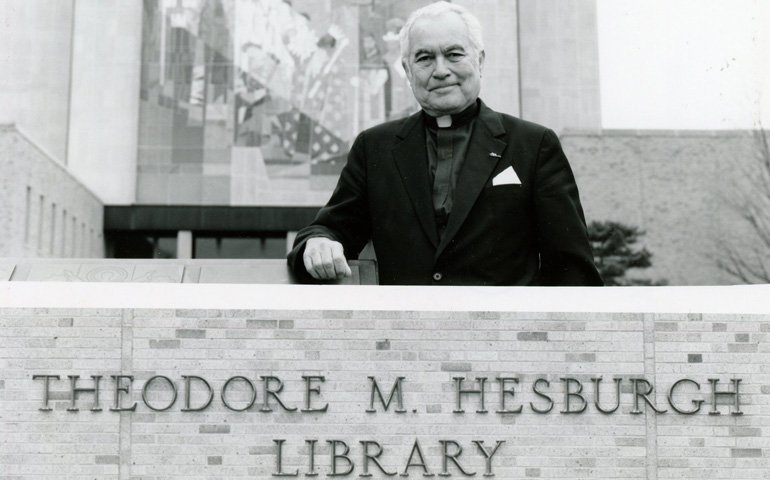

Holy Cross Father Theodore Hesburgh, then president of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, is seen in this 1987 file photo. (CNS)

This summer marks the 50th anniversary of the Land O'Lakes statement on Catholic higher education. Spearheaded by Holy Cross Fr. Theodore Hesburgh, who was president of the University of Notre Dame and of the International Federation of Catholic Universities, and informed by the contributions of many luminaries of the Catholic academy, including my great mentor, Msgr. John Tracy Ellis, the document set forth a vision for Catholic higher education that, for good and ill, became dominant in the years that followed. Today, I commence a series of articles on the Land O'Lakes statement, how it played out, and the responses to it today.

As is so often the case, many of the champions of the statement, and many of the detractors, seem not to feel constrained by either the text or by an awareness of the times from which it emerged. These constraints are different. The text was seminal and, just so, developments that cited it as providing warrant are often lumped in with it. The failure to appreciate the circumstances in which it was issued is simple intellectual sloth, usually put in aid of an ideological agenda.

1967 was just two years after the close of the Second Vatican Council. There, at the invitation of St. Pope John XXIII and in the course of four sessions of deliberations, the church threw open its windows to let in some fresh air. The council fathers committed the church to engaging the world, not dominating it, and recognized that the world enjoyed a proper autonomy from the realm of the ecclesiastical:

If by the autonomy of earthly affairs is meant the gradual discovery, exploitation, and ordering of the laws and values of matter and society, then the demand for autonomy is perfectly in order: it is at once the claim of modern man and the desire of the creator. (Gaudium et Spes 36)

The council's decree on education, Gravissimum Educationis, also pointed to the need for a kind of independence of Catholic colleges and universities, as well as the obvious linkages or "harmony" between faith and reason that has been a hallmark of the Catholic intellectual tradition. The section that deals with higher education states:

In those schools dependent on her she [the church] intends that by their very constitution individual subjects be pursued according to their own principles, method, and liberty of scientific inquiry, in such a way that an ever deeper understanding in these fields may be obtained and that, as questions that are new and current are raised and investigations carefully made according to the example of the doctors of the Church and especially of St. Thomas Aquinas, there may be a deeper realization of the harmony of faith and science. Thus there is accomplished a public, enduring and pervasive influence of the Christian mind in the furtherance of culture and the students of these institutions are molded into men truly outstanding in their training, ready to undertake weighty responsibilities in society and witness to the faith in the world.

It was with these decrees in mind, and their own experiences in Catholic higher education as well, that the university leaders gathered at Notre Dame's summer retreat center and drafted this document.

The opening lines of the text address a core problem that had plagued Catholic higher education even into the 1960s:

The Catholic University today must be a university in the full modern sense of the word, with a strong commitment to and concern for academic excellence. To perform its teaching and research functions effectively the Catholic university must have a true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical, external to the academic community itself. To say this is simply to assert that institutional autonomy and academic freedom are essential conditions of life and growth and indeed of survival for Catholic universities as for all universities.

These educational leaders recognized that the council had proposed, and the long history of Catholic higher education being second rate demanded, that Catholic universities improve and that a necessary precondition of such improvement was to free themselves from clerical control. They mention "lay" authority as well, and in our time, it is lay control that is now more worrisome, a point I will focus on subsequently. But in their day, the problem was clerical control.

We must travel back in time. I mentioned Msgr. Ellis who, in his 1989 memoirs, wrote about his being invited to speak at the International Congress of Historical Sciences meeting in 1955 in Rome. The Rector of Catholic University, Bishop Bryan McEntegart, opposed Ellis' going and so Ellis did not go. Eight years later, this veto by the rector would be replayed when McEntegart's successor, Bishop William McDonald, barred four theologians from speaking on campus. Asked about this by a reporter, Ellis said that that sort of thing had been going on "at this university for a decade or more." Looking back on the twin episodes in his memoirs, Ellis wrote, "Today the invitation to speak at the Roman congress would in all likelihood be accepted or declined without reference to either ecclesiastical or academic authority. But the 1960's were a different time in that regard, a time when ecclesiastical authority was much more heeded than it is in the 1980's."

The Land O'Lakes statement's embrace of a certain institutional autonomy did not in any way require a shedding of the Catholic identity of the university. It is not shy about the importance of theology to the life of a Catholic university, calling it "essential to the integrity of a university." The document also followed Vatican II in urging that theological investigation "serve the ecumenical goals of collaboration and unity." I note that Notre Dame took this last provision and made itself home to some of the nation's foremost evangelical scholars ever since. The text calls for theology to engage in interdisciplinary dialogue and perceives such dialogue as beneficial to all academic disciplines. "There must be no theological or philosophical imperialism; all scientific and disciplinary methods, and methodologies, must be given due honor and respect," it states. "However, there will necessarily result from the interdisciplinary discussions an awareness that there is a philosophical and theological dimension to most intellectual subjects when they are pursued far enough. Hence, in a Catholic university there will be a special interest in interdisciplinary problems and relationships."

Autonomy did not imply a lack of relationship between the university and the church to the drafters of the Land O'Lakes document, and they looked to their secular counterparts as a model. "Every university, Catholic or not, serves as the critical reflective intelligence of its society. In keeping with this general function, the Catholic university has the added obligation of performing this same service for the Church," it states. "Hence, the university should carry on a continual examination of all aspects and all activities of the Church and should objectively evaluate them. The Church would thus have the benefit of continual counsel from Catholic universities. Catholic universities in the recent past have hardly played this role at all. It may well be one of the most important functions of the Catholic university of the future." This kind of balance characterizes the entire text.

The document also sees the students as engaging in a vibrant liturgical life, in works of service, matching their theoretical learning with hands-on service, and mentions in particular "inner-city social action" and "personal aid to the educationally disadvantaged."

The other aspect of the text that is especially worthy of note is found in the preamble where Jesuit Fr. Neil McCluskey who served as secretary to the group, emphasizes the provisional character of the statement and the need to revisit the discussion regularly. Regrettably, this never really happened. There were intra-university discussions, but no systematic attempt by the leaders of several universities to meet regularly and discuss revisions to the text and its goals based on the experience that is uniquely afforded by implementation, to say nothing of the fact that both the church and the academy were going through periods of swift and often chaotic change.

So, what was the fuss? Why is this balanced and sober text so maligned? Do the insights still seem relevant? What did they get wrong? Monday, we will begin to answer those questions.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Sign up to receive emails, and we will notify you when Michael Sean Winters publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.