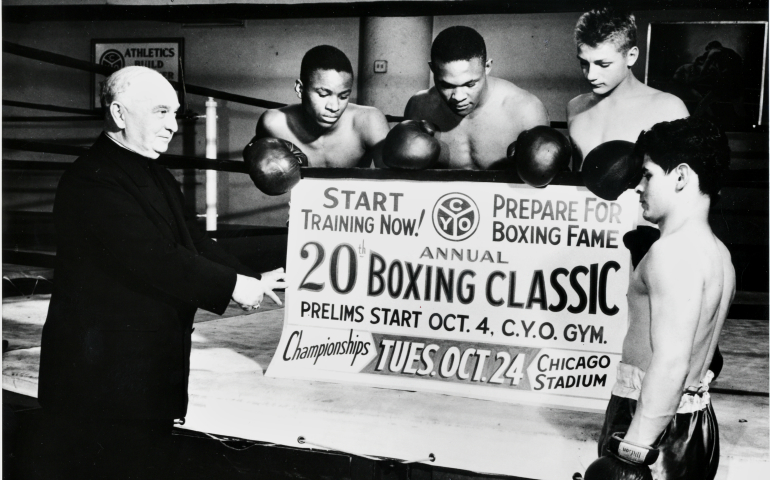

Bishop Bernard Sheil and boxers in a 1950 promotional shot for Catholic Youth Organization boxing championships (Archdiocese of Chicago’s Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Records Center)

Yesterday, I began my review of Timothy Neary's wonderful book Crossing Parish Boundaries: Race, Sports, and Catholic Youth in Chicago, 1914-1954. Having examined the early years of interracial tensions and even hostilities, the book turns to its hero, Auxiliary Bishop Bernard Sheil of Chicago.

Sheil was from a "financially secure family," which Neary notes "removed from the Sheil family many of the economic excuses for bigotry common among ethnic and racial groups competing for economic and social status in the industrial order." Sheil attended St. Viator College, a boarding school for boys, where he was mentored by Viatorian Fr. William Bergin, a man who instilled in his young charges a profound commitment to Pope Leo XIII's seminal encyclical Rerum Novarum. St. Viator also counted among its alumni two other great churchmen, Fulton Sheen and John Tracy Ellis.

Sheil's charismatic personality came to the attention of Chicago Archbishop George Mundelein, who was appointed in 1915, and in 1924, Sheil was named chancellor. Four years later, he was named auxiliary bishop.

Sheil had worked as a chaplain at the Cook County Jail and later at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, which "left the young priest with two lasting convictions. First, society must take responsibility for juvenile delinquency. Second, the church should employ organized recreational and leisure activities to promote Christian and democratic principles among youth."

In 1930, Sheil founded the Catholic Youth Organization, putting those convictions to work. There had been parish sporting events previously, but these had followed the racial and ethnic boundaries that the parishes did. "The CYO differed from other youth leagues and organizations," Neary writes. "From its inception, Sheil invited boys and girls regardless of ethnicity or race to participate in CYO activities."

The organization acquired four floors in the Congress Bank Building, in the heart of downtown, and filled it with locker rooms, boxing rings and bowling alleys.

"We are rescuing our boys from speakeasies, gangster hang-outs, street corners, and from the other temptations that lie in wait for discontented youth," Mundelein, now a cardinal, said at the center's dedication. But most of the CYO activities happened out in Chicago's many parishes, building on that existing network, and advertising through the archdiocesan newspaper and parish bulletins. Those who decry "organized religion" forget that disorganized religion is its opposite.

Sheil crafted a "My CYO Creed" for the participants:

1. To love God and country; 2. To love the poor and afflicted; 3. To acquire physical and mental courage; 4. To understand myself and my group; 5. To strive for a better life for myself and my fellowmen; 6. To promote social justice by rigid application of the principles expressed in the Encyclicals of Leo XIII and Pius XI; 7. To foster the spirit of American democracy as expressed in the deeds of Jefferson and Lincoln; 8. To abstain from excesses of any kind; 9. To emulate virtues of the victorious Apostolate of Christ; 10. To be humble in victory; undaunted in defeat.

The list holds up pretty well, although revisionist historians have complicated our understanding of the "deeds" of Jefferson.

Neary notes that the CYO, while founded to confront juvenile delinquency and to promote the Americanization program so characteristic of Mundelein's tenure, was distinguished quickly from groups like the YMCA precisely because it was not segregated by race.

In the heart of "Bronzeville", the neighborhood with the highest concentration of black Chicagoans, Sheil converted a building at St. Elizabeth into "Sheil House," a kind of community center. During the summer months, it hosted a day camp, with morning socialization and recreation activities and afternoon field trips to the city's cultural gems. It was open to all, regardless of religion.

It was in the boxing ring that Sheil's commitment to interracialism first came before the public eye. Neary quotes Malcolm X who said, "The ring was the only place a Negro could whip a white man and not be lynched." Joe Louis won the world championship belt in 1937. Black and white CYO boxers not only competed against each other, but when the Chicago team went to other cities to compete, they went as teammates. Thousands attended interracial matches at Chicago Stadium and other venues. In 1936, three CYO boxers were on the U.S. Olympic boxing squad at the Berlin Olympics, at which the legendary Jesse Owens disproved with his speed the Nazis' view on Aryan racial superiority.

The CYO also opened its doors to women, although the number of sports available to them were fewer. Still, runner Mabel Landry Staton summed up the social significance of the racial integration Sheil pursued: "We were the only interracial team running at the time. And we beat everybody."

Mundelein died suddenly in 1939, and Sheil never had the same degree of support from, nor rapport with, Mundelein's successor, Archbishop Samuel Stritch. The Second World War brought another wave of domestic migration and the black population of Chicago swelled. By 1950, blacks were 14 percent of the city's population and by the end of the decade, a stunning 23 percent.

This created a "tipping point" in the eyes of some white folk. "They no longer saw black involvement in the CYO as the participation of just one ethnic group among many," Neary writes. "Rather, they felt that racial minorities had overrun the organization. Some even referred to the CYO derisively as the 'Colored Youth Organization.'"

In 1954, Sheil resigned as director of the CYO and the program became decentralized. The conservative political winds blowing through both the church and the state in the 1950s did not fill Sheil's sails ever again.

Neary catalogs other aspects of the CYO. Sheil started a CYO social service department that provided a range of services to poor children and families. In 1948, Sheil appointed a black laywoman, Dora Somerville, as director of the Sheil Guidance Clinic, daring to push gender boundaries as he had pushed racial ones.

Neary looks at the central role Sheil's commitment to organized labor played in shaping his thinking, including the opening of a labor school, the Sheil School of Social Studies, in 1943. He discusses Sheil's friendship and collaboration with Saul Alinsky on the Back of the Yards project. One gets exhausted just reading about all the different and varied initiatives Sheil began.

Chicago was subsequently home to another moment of interracial historical significance, as hundreds of thousands of Chicagoans filled Grant Park on election night 2008 to celebrate the election of the first black president. That moment, as had so many moments in Sheil's career, held out the hope that America had lanced the boil of racial animus, but it turns out the sin of racism runs deep.

Still, this wonderful book tells the tale of an extraordinary bishop doing extraordinary things in the Windy City, confronting societal ills boldly and devising efforts to counter them. How many lives were made better by Sheil's efforts — hundreds, thousands perhaps?

Let those lives be the legacy of his efforts, not the fact that racism remains uncured. And let us hope that Chicago might see a similar burst of ecclesiastical energy in the years ahead.

[Michael Sean Winters is NCR Washington columnist and a visiting fellow at Catholic University's Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies.]