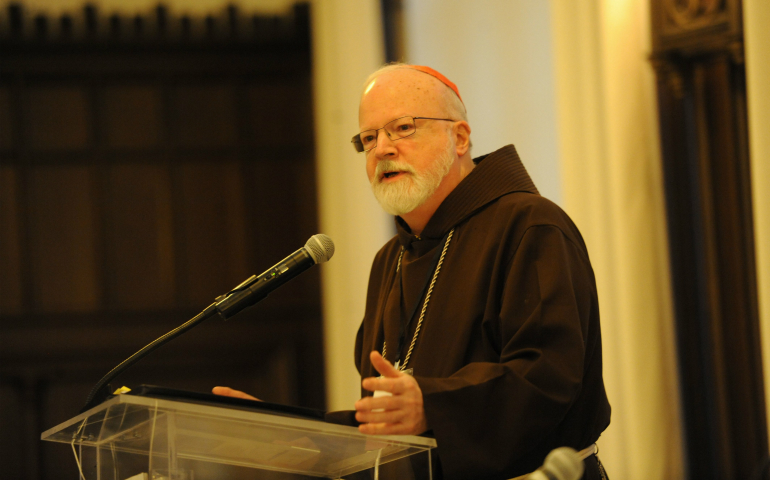

Cardinal Sean O'Malley of Boston addresses the symposium "Erroneous Autonomy: The Dignity of Work" organized by the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies at The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., Jan. 10 (Courtesy of The Catholic University of America.)

Editor's note: This talk, titled "The Dignity of Labor," was delivered Jan. 10 at the symposium "Erroneous Autonomy: The Dignity of Work" organized by the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies at The Catholic University of America, Washington D.C.

Today's theme, the dignity of labor, for me isn't some sort of an abstraction, because I lived so intensely a ministry to workers who were exploited, who lived in fear and for whom their work did not represent a life giving, dignified human activity.

When I was ordained a priest in 1970, the wars were raging in Central America. Often rightwing governments supported by U.S. government versus Marxist insurgents backed by Cuba with the people caught in the middle. People naturally prefer to remain in their homelands, in familiar surroundings, where one is truly their home. But sometimes circumstances are such that people need to leave their homeland and find a new place and make a new start.

The O'Malleys did not leave the famine-stricken west of Ireland because of the lure of food stamps or welfare packages or wanderlust or desire for travel but as an alternative to starvation, religious persecution and annihilation. In his play, "The Irish ... and How They Got that Way," by Frank McCourt of Angela's Ashes fame, there is a great song in it where the Irish immigrants are singing, "We came to American because they say the streets are paved in gold, but when we got here we discovered that the roads weren't paved at all and that we had to pave them."

I often share with people my experiences as a young priest being assigned as the director of El Centro Catolico Hispano on Mount Pleasant Street in the heart of the barrio. The coyotes would bring people from El Salvador and drop them off in front of my office. For many, it was the go now, pay later plan. If you didn't pay a hefty part of your weekly salary for the first year, they threatened to kill your relatives back home.

I often share with people that on my first day on the job a man came into my office, sat down across from my desk and he began to weep uncontrollable. He couldn't even speak, he just handed me a letter. I opened the letter and it was from his wife back in El Salvador who was castigating him for have abandoned his family. When he finally composed himself he explained to me that he was a farmer but with the war it was impossible for him to continue to work the land, and so like so many from his village he came to Washington. He said, "I live in one room with 10 men from my village, and we wash dishes in restaurants. I wash dishes at one restaurant at noon and at another at night. I walk to work so not to spend any bus fare. I eat the food on the dirty dishes so that I don't need to spend money on food so that I can send all of my money home. I have been sending all of my money that I earn every week for six months and my wife has not yet gotten one letter from me.

And the poor man was desperate. I said, "Well do you use money orders or checks?" He said, "No father, I use cash. I put it in envelops and put stamps on like I was told to do and I drop it in that blue mail box on the corner." I looked out my window, I saw the blue mail box. The problem was that it was just a stupid trash bin.

It became so apparent to me how difficult it is to be in a foreign land, not knowing the language or the customs. To live in fear of discovery. To do the hardest jobs for the least pay. To endure humiliations and hardships only to be able send money home to keep your family alive.

In those days, thousands of undocumented workers were fleeing violence and hunger. I was their pastor for 20 years. At El Centro Catolico, we were very successful of working with the women to get them visas because there was such a demand for domestic workers. A big part of my ministry was working with domestic workers along with Sister Manuela, a Spanish nun, we started an organization called Asociación Internacional de Tecnicas del Hogar, the International Association of Household Technicians. [Washington, D.C. Mayor] Marion Berry in those days established a commission to set a new minimum wage, and he named Gloria Steinem and me as co-chairs. Talk about the odd couple. But we were instrumental in setting the highest minimum wage in the United States at the time. The workers, however, who were the most exploited were not the undocumented or the household workers, but mostly those women who worked in the diplomatic missions in Washington, the servants. In the embassies to the White House, in the embassies to the Organization of American States, the World Bank, the Inter-American Monetary Fund, in many other international agencies and organizations that gave visas for household domestic workers, many middle class families from developing countries are used to having servants, but they didn't necessary treat them like Lord and Lady Grantham from Downton Abbey.

During my years at El Centro Catolico, never a week went by that we were not involved in some attempt to extricate household workers from an embassy or the home of a diplomat where a woman was being exploited, sexually or economically or living in virtual slavery. To cite some examples, one young woman came to us seeking relief. She was brought from Colombia in her late teens ostensibly to be an au pair, but when she got here, she discovered that the streets were not paved. She had to cook, clean, wash and iron, cut the grass, shine the man's shoes, wash the car and care for the children. Seven days a week, from six thirty in the morning until 11 o'clock at night and she never received a penny. Every month they would give her a receipt saying how much they were charging for her room and board and her original air fare from Colombia. We, of course, looked for the meanest lawyer that I could find to sue the people, but being diplomats they had immunity so there was nothing that could be done. Her boss was the personnel director for the Organization of American States. He like so many other diplomats would keep the passports of their servants so that they couldn't get another jobs. I once tried to retrieve the passport of a young woman 19 or 20 years old working in the Paraguay embassy, because she wanted to change jobs. She said they were treating her very mean. The ambassador had her sent back to Paraguay and in prisoned for a month in one of Stroessner's jails. [Alfredo Stroessner was president of Paraguay 1954-1989.] We brought her back by sneaking her out through Brazil, and put her on "60 Minutes."

When I would speak to these offending diplomats they would always say "Oh Father, lo tratamos como un miembro de la familia." — "We treat her like a member of our family." My rejoinder was always, "I am so glad I am not a member of your family."

So I truly understand and support the labor movement. Without organized labor, workers are so vulnerable. The recent elections reveal the crisis of income inequality in our country. The waning of organized labor is a huge factor. A generation ago, CEOs earned 25 times what the average worker earned. Today it is up to 325 times of what the average worker gets. As a young priest here in D.C., I used to participate in the annual Labor Day Mass at the Capuchin parish, The Shrine of the Sacred Heart, which has a statue on 16th Street honor Cardinal [James] Gibbons [of Baltimore 1834-1921], who defended the rights of Catholics to join unions. Monsignor [George] Higgins [1916-2002] used to speak often of "economic citizenship." Economic citizenship requires a voice in the decisions that shape your life and your livelihood, a voice in your job, your community, and your country. Economic citizenship requires a sense of recognition and respect for the work you do, the contributions you make and your inherent dignity as a child of God.

Last month, at its annual dinner, the Archdiocese of Boston Labor Guild celebrated the 50th Anniversary of the Cushing-Gavin Awards, named for Cardinal Cushing, who established the Guild and, Fr. Mortimer Gavin, SJ, who was both a professional mediator and Guild chaplain. The awards are presented each year to persons from union leadership and corporate management who are distinguished by their advocacy for fair and equitable policies for the men and women of labor.

The Archdiocese's Guild stands in a long line of "labor schools" which were established in dioceses across the United States during the twentieth century, for the purpose of promoting Catholic social teaching on the rights of workers and fostering the common good of our country. Continuing this mission, the Labor Guild organizes educational programs throughout Archdiocese on an ongoing basis, offers a venue for negotiations between labor and management, and provides a visible symbol of the continuing commitment of the Catholic church to work with other institutions and organizations in support of just and productive economic policies that honor the contributions of all workers.

It is good to be able to participate in today's conference, which is part of a larger project assessing the concept of "autonomy" in personal and societal life. The Second Vatican Council addressed that topic in its document Gaudium et Spes, saying, "If by the autonomy of earthly affairs we mean that created things and societies themselves enjoy their own laws and values which must be gradually deciphered, put to use and regulated by men, then it is entirely right to demand that autonomy."

This particular statement by the Council has been regarded as particularly significant since it serves to dispel the idea that human creativity, in science, politics, economics and the arts, is somehow opposed to or constrained by religion. At the same time, in other statements the Council noted that autonomy, interpreted apart from moral limits and in isolation from any religious meaning, can be seriously threatening to human welfare and the common good. When work and creativity are located within a moral and religious framework, together they serve to enhance human dignity and social justice.

The teachings of the Church and the advocacy for the dignity of work have a long-standing relationship. In the scripture of Genesis, the first book of the Bible, it is clear that God intends humanity to actively collaborate with the work of shaping the created order. During the recent weeks of the Christmas season we observed the birth of Christ who, throughout his life is identified as a carpenter's son. In many classical works of art, the young Jesus is depicted at work with Joseph. The scriptural basis of work has been with us for two thousand years, but our understanding of human labor entered a new dimension in the past 150 years. During that time there have been several moments of new understanding of the value of human work, of the person as a worker and collaborator with God in the daily activities by which men and women "earn a living" and also contribute to the good of society.

During the time of the Industrial Revolution, from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, the world experienced a new era of invention and production in Europe and North America. While this development brought major benefits to society, it did so at great human cost, particularly related to the working conditions and the living conditions of the people who made industrialization possible. From factories to mines, to agriculture and businesses, very often workers received few of the benefits of the innovations they were producing. Wages, working conditions, housing and health care were all meager, providing little to no recognition of the workers' contributions. The Church, much like secular society, took time to recognize the depth of the moral challenge posed by industrialization, but it found its voice in the late nineteenth century in an encyclical by Pope Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, the Condition of Labor. This landmark document began the on-going collaboration of the Catholic Church and the labor movement in the United States. It addressed the need for a just wage by which the worker could provide for a family — in the United States this became "a just minimum wage"; it argued for protection of workers in places of work; and it asserted the moral right and foundation for unions, whereby workers could negotiate with the owners of the factories and businesses where they labored.

During the twentieth century there was a growing alliance of the Catholic Church and the labor movement as the voice of the Church's teaching and its legislative advocacy in Washington and in states across the country identified the moral reasons for supporting the rights of workers.

Following World War II, industrialization began to spread across the world and what we today call the global market began to emerge. The sources of this development were twofold, the process of decolonization in Asia, Africa and Latin America; and the political-economic creation of institutions facilitating political and economic activity beyond a nation's borders. This process of internationalization was in good part shaped by the United States and the institutions that emerged from the Bretton Woods Conference, including the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and eventually the World Trade Organization. These in turn were complemented by the United Nations, including the International Labor Organization. These developments melded domestic and international policies, calling for a new framework for understanding the relationship between labor and management. In the 1960's, Pope Saint John XXIII called for a country's economic and social goals to include consideration of the international common good. The Church also recognized the need for international institutions and agreements to address the growing complexity of an interdependent world.

A key aspect of internationalization was the expanding role of trade, which offered new opportunities but also could impose heavy costs on a society, particularly in terms of loss of jobs and industries. An early response to this challenge was that increased international trade required the implementation of domestic policies, to provide for the needs of workers and industries negatively impacted. It is increasingly clear that this concern is of great importance in our country and throughout the world today.

Increasing international trade and financial relationships, combined with rapidly advancing technological innovation and the world of the internet, have produced what we call globalization. This development has produced enormous amounts of wealth but not a fair and just distribution of the proceeds. All too often we hear commentary about winners and losers in globalization, without recognition of the costs for workers and for nations. Pope Saint John Paul II, who was deeply familiar with the world of work through his personal experience with Solidarnosc, the Polish labor solidarity movement, grasped the significance of globalization. In the encyclical Centesimus Annus, issued in 1991 on the centennial of Pope Leo's Rerum Novarum, he observed that globalization, like technology, had its own logic but lacked morality. Pope St. John Paul emphasized that international leaders and institutions have the responsibility to establish a moral framework which can assess and direct the purposes and the consequences of globalization.

Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI addressed the importance that the global economy serve the needs of humanity and not be its master. Both were committed to humanizing economic life. Pope Francis now brings a distinctive perspective to this work. As a Jesuit, he has lived the Society of Jesus' commitment to social justice. As Archbishop of Buenos Aires, he was a leader of the global South, a part of the world which is continually being impacted by shifts in globalization. And his personal commitment to the poor has made the issues of work, workers and the economy an abiding concern for his ministry.

Pope Francis begins his advocacy for the dignity of labor with recognition of the human person, the cornerstone of all Catholic social teaching. This means that each individual is to be protected by a moral framework of human rights and that the work a person does, whether manual labor, mining or intellectual and professional work, is understood as an expression of their dignity. This theme is woven through the history of Catholic teaching on labor. In the early years of the Industrial Revolution it was the basis for advocating that society should not relegate the wages workers earned to the vagaries of the laws of supply and demand, but that wages needed to be adjusted on moral grounds, to provide a "living wage" that would support a family. This argument continues to be made today in the campaign for a higher minimum wage across the country.

The dignity of work was powerfully invoked by Pope Saint John Paul II in the encyclical On Human Work as he maintained that all workers should see their labor as part of God's ongoing work in the world. Continuing this theme, Pope Francis' Laudato Si', his 2015 encyclical on the environment, encourages all workers to see themselves as participants in God's continually enhancing creation through new discoveries and new understandings of what is possible. In the encyclical, the Pope also makes clear the importance of including religious and moral principles in our decisions about what our societies produce and how our choices affect the environment.

During the later years of the 20th century and in our own time now, the labor movement has come under pressure from industry and political process at the state and national level. The case for unions is rooted in the Catholic sense of our responsibilities to each other as members of the human family, we are not to be left alone in society and or in the economy. We are called to support the right of workers, all workers, private and public sector workers, to organize and be represented in the marketplace and in negotiations by an institution, the union, which gives workers leverage and a voice in the major decisions affecting them and their families.

In his words and actions, Pope Francis has been a strong public advocate for the dignity of labor, including making interventions when companies were intending significant elimination of jobs. He has argued strongly that in the midst of the forces of technology and globalization, people cannot be reduced to arguments for greater efficiency. The Pope has stressed the need for equity, for fairness in our understanding of what constitutes a just economy and the role of workers.

In his 2013 Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, the Joy of the Gospel, Pope Francis provides a distinctive contribution to Catholic social thought by listing his "Four No's" regarding the economy:

- No to an Economy of Exclusion;

- No to the New Idolatry of Money;

- No to a Financial System which Rules Rather than Serves;

- No to the Inequality which spawns violence

Pope Francis acknowledges the progress of science and technology but believes that the power of the economy, like all power, requires observance of moral limits. Pope Francis' concern for the poor leads him to focus on the marginalized and excluded, but his assessment of contemporary attitudes and ways of thinking about money, financial institutions and public policy lead him beyond the poor to larger groups in society who feel both excluded and abandoned in the modern economy.

Both Popes St. John Paul II and Francis have recognized that market forces and globalization are facts of life that in some form are here to stay. But both recognize the need for moral direction for these powerful realities. John Paul II recognized the positive potential of globalization, but refused to believe that its own dynamics would produce a just global economy, arguing that political and legal limits need to be set within states and nations, in order to protect social and distributive justice. Pope Francis brings his own perspective, warning us of the autonomy of markets and financial speculation and questioning blind trust in the unseen forces and invisible hand of the economy. In both cases, these observations and the challenges they present to us are rooted in long-standing statements of Catholic thought and teaching.

As we proceed into the 21st century, there are particular concerns of the labor movement in the United States today. The consequences of the financial crisis of recent years and the great recession have put issues of wages and inequality at the forefront of our political and economic life. Writing in The Financial Times, the British economist Mark Wolf draws on a report of the McKinsey Global Institute which illustrates that "real income stagnation over a far longer period then any since the Second World War is a fundamental political fact and notes that "the proportion (of workers) suffering from stagnant incomes has been between 20 and 25 percent." Presumably many of those caught in this pattern of stagnation have solid occupations and years of experience, but they do not see themselves benefiting from the fruits of a post-industrial economy. The point earlier that globalization can produce great wealth, but by itself will not address distributive justice is reflected in these numbers. There must be commitments from the private sector and public policy to address stagnation; this is a human and moral imperative.

A related issue, now widely debated in our country, is the minimum wage. Catholic teaching concerning a just wage is directly related to the value and dignity of human labor, which is never determined only by factors of supply and demand. A just wage values a worker's worth as a person as well as an employee. Debates about minimum wages are most relevant to those closest to poverty. Catholic teaching about the option for the poor, places us in support of reasonable initiatives to raise the minimum wage.

We are also in the midst of a debate as to how best to provide health care for our citizens. In our economy health insurance is often as important as salary or income. Affordable health care is foundational for the well-being of individuals and families and lack of health care directly threatens human dignity. The technical details concerning health care policies are many and complicated, but our moral obligation not to abandon people in their times of need is clear.

And, as we are all well aware, there are many voices in the United States and Europe that speak of connections between immigration and employment. In our country, the Catholic Church and the labor movement have been deeply connected to immigration policy and to our immigrant populations. We are blessed that our society and our economy are strong enough to be both a source of security for citizens born here and a source of protection for those fleeing poverty and violence. While every country must balance numerous factors in determining immigration policy, particularly with regard to security, our national history and our principles call us to be a welcoming society. For decades the U.S. Catholic Bishops Conference has called for systematic immigration reform, including protection of undocumented individuals and families. As we continue to advocate and work for these important issues, we welcome the opportunity to work with the men and women of American labor.

Today's conference has brought together people with many different talents, skills and vocations to examine these broad questions of the Dignity of Labor at a time when new challenges need new responses. It is a privilege to have been able to participate in this conversation.

[Cardinal Sean O’Malley is archbishop of the Boston.]