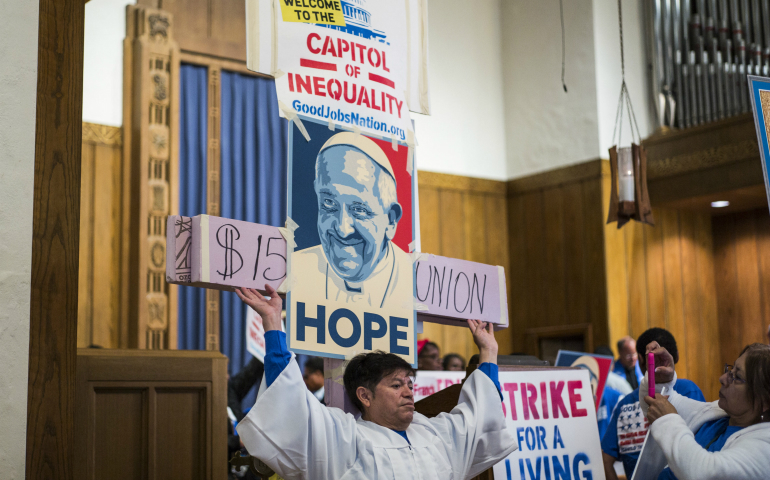

Contract workers from the U.S. Capitol and other federal buildings rally at the Lutheran Church of the Reformation during a strike over wages in Washington in September 2015. (CNS photo/Joshua Roberts)

Last Sunday, the sermon you heard probably focused on the Lord Jesus' articulation of a "higher law," in his call to turn the other cheek, offer one's cloak as well as one's tunic, to go the extra mile. Or you might have heard about how grace perfects nature insofar as none of us can be "perfect as our heavenly Father is perfect" without large infusions of divine grace. Or the homilist might have focused on Paul's letter to the Corinthians, with its warning against human pride and reminder that we are temples of the Holy Ghost.

I should like to call attention to the first reading, from the Book of Leviticus. It is a short passage, so it is easily printed in full:

The Lord said to Moses,

'Speak to the whole Israelite community and tell them:

Be holy, for I, the Lord, your God, am holy.'You shall not bear hatred for your brother or sister in your heart.

Though you may have to reprove your fellow citizen,

do not incur sin because of him.

Take no revenge and cherish no grudge against any of your people.

You shall love your neighbor as yourself.

I am the Lord.'

The passage shows how incorrect are those facile portrayals of the Hebrew Scriptures and the law they contained as harsh and unmerciful, a fact further attested by the beautiful psalm we sang: "Merciful and gracious is the Lord, slow to anger and abounding in kindness. Not according to our sins does he deal with us, nor does he requite us according to our crimes."

The author of Leviticus does something else, however, something that is vitally important and which is, I fear, often overlooked in preaching and catechesis. Before calling Israel to bear not hatred toward a brother or sister, to take no revenge and to love our neighbor as we love ourselves, the author sets forth the doctrinal basis of the morality that follows: "Be holy, for I, the Lord, your God, am holy."

Too often, we Catholics are not taught the linkages between our doctrinal claims and our moral claims, be those moral claims about matters of social justice or sexual morality or personal conduct. Our dogma is siloed, as it were, from our morality, and the different parts of Christian morality are often as not siloed from one another. This facilitates the cafeteria Catholicism on both the left and the right, but it does something worse. Untethered from their roots in doctrinal beliefs, our religion is the more easily reduced to morals and, in a vibrant, commercial, alluring culture like our own, those morals are unlikely to withstand the whirlwind.

Two years ago, I read and reviewed Meghan Clark's wonderful book, The Vision of Catholic Social Thought: The Virtue of Solidarity and the Praxis of Human Rights. After noting many accomplishments in her work particular to the field of Catholic social thought, I wrote:

The most important contribution of this book, however, is Clark's examination of the philosophical and theological anthropology that undergirds Catholic social teaching. In the face of conservative critics who question the value or binding nature of the church's teachings on social justice, Clark demonstrates that these teachings are founded on the very same principles that ground the church's teachings on human sexuality and the dignity of human life.

The human person is created in the image of God, but for the Christian, that God is Trinitarian. So, the imago dei is an imago trinitas. Human moral excellence, conceived as a private, personal, individualized achievement is not enough. The church teaches, and the Catholic is called, to imagine and work for a society in which the bonds of solidarity take as their standard the endless, ineffable self-giving love that is the Holy Trinity.

The Nicene Creed that we recite every Sunday does not mention any particular ethical claims. It does not proscribe abortion nor does it advocate the minimum wage. But, in Clark's rendering, all the teachings of the church are rooted in an understanding of the human person that is, in turn, rooted in the triune God we confess in the creed. This linkage has never been so concisely and ably demonstrated as Clark achieves here.

When I hear a conservative Catholic argue that setting the minimum wage is a mere matter of prudential judgment, I cringe because they are unwittingly denying that how we treat our fellow men and women is called to reflect the love within the Godhead itself. When I hear a liberal Catholic argue that God has nothing to say about human and sexual love, I cringe for the same reason. A commitment to dogma does not require one to become dogmatic. And without such a commitment to dogma, the Catholic faith is just about being kind. "Do not the pagans do as much?" Jesus asked in the Gospel.

Preachers: Let your people hear how our moral claims are rooted in our doctrinal claims. I have often teased my bishop friends that if you gave all the bishops a paper and a pen and five minutes and asked them to write down the connection between the Doctrine of the Trinity and, say, the church's teaching on economic matters or on contraception, I am betting the answers would not be consoling. Yet, without that connection, our morality just one among many moralities, unlikely to persuade, fragile for some and reactionary for others, but in no sense a vibrant and responsible way of living.

John Henry Newman wrote: "From the age of fifteen, dogma has been the fundamental principle of my religion: I know no other religion; I cannot enter into the idea of any other sort of religion; religion, as a mere sentiment, is to me a dream and a mockery." When I was 15, I cared about the Red Sox but as I approach 55, I am in full agreement with Newman. Religion as sentiment is a dream and a mockery. Our religion, our Catholic religion, is a dogmatic one. I hope preachers will take the occasion to ground their sermons on all moral matters in the dogmatic claims from which that morality springs.

[Michael Sean Winters is NCR Washington columnist and a visiting fellow at Catholic University's Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies.]