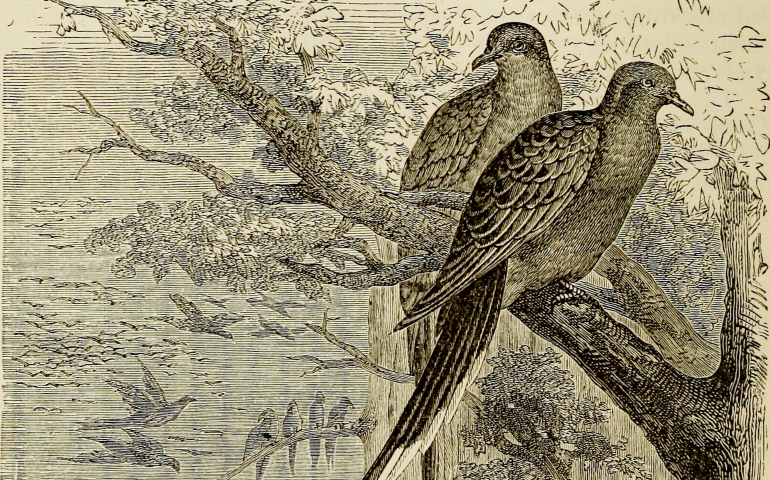

An 1873 illustration of passenger pigeons (Wikimedia Commons/Internet Archive Book Images)

When we talk about life after death, we often get a little fuzzy. Where does our body go? Where does our spirit go? Whence our breath?

These are good questions and while many say they have answers, no one has much data. Even the most rational of us may speak of our mother joining our father in heaven when she stopped breathing. Romantically, many people bury themselves next to their dead, like my mother who wants to be buried next to my father in a previously bought plot thousands of miles away from her home. Why would anyone oppose these "romantic" notions or behaviors?

A 2015 book by M.R. O'Connor, Resurrection Science: Conservation, De-Extinction and the Precarious Future of Wild Things, may help us get a few new metaphors to approach the unapproachable. It chronicles what is called de-extinction science, which tell us that at a time of alarming levels of species extinctions, there are people working through genetics to bring some extinct species back, like the passenger pigeon.

The Anthropocene — a geological period defined by the major impact of humanity on the Earth — has already dawned, according to some scientific experts, and humans now know how to do things that can reverse some of the damage we continue to do. The de-extinct species are likely to live in zoos and not among us, but they will still live. We will resurrect them. Our technological prowess appears to have few limits.

I saw a sign in Connecticut once telling me I was at "Bad Corner Road." That title applies to the new confusion around death and dying newly muddled by de-extinction science. We could be turning a bad corner.

In a world of self-driving cars and recombinant genetic magic, what does death or extinction mean for those of us who love the environment? There may be great science here, but I am concerned about religion.

I don't think we need to fear death, or extinction, in the first place. I believe in evolution so much that I think things are always being born and always dying. I even pray the "Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep" bedtime prayer like this: "Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep, If I should die before I wake, may another sister take my place." I won't be upset if her genetic material is different from mine, either.

I don't want to live forever. I do want to live as long as I can as happily as I can. I am greedy for life. Likewise, I am not so afraid of death that I will de-welcome my getting out of the way on behalf of the new and the next.

Can we ever get back to an environmental moment that is foundational or fixed? Why would this generation become the foundational moment in time or space? Because we know how to de-extinct species or make robots that can do so much of our work? Or because somehow we've taken the Anthropocene straight to our heads? Do we really think we are supposed to last because we are so good? Isn't that a kind of anti-creation pride, one that dares to defy the seasonal pattern of creation that things live and then die and then live again?

My "baby" brother, seven years my younger, died last month. His loss has been devastating. We were planning my 70th birthday. I cried through the entire NCAA men's basketball final last week because he wasn't there to see North Carolina win and to text with me throughout the game.

I will miss him every day the rest of my life. He was my best friend. He was the only person who knew all but seven years of my stories. He taught me how to dance the "Shag." We often sang "Margaritaville" or "(Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay" together. Now he is gone, and I am terribly sad for him, to die so young. I am brokenhearted for me as I now know the loneliness I will feel the rest of my days.

Still, and more, I don't want to intrude on creation's great vastness and seasonality to rage at death. Death is the mother of beauty, as the poet Wallace Stevens wrote. Jesse is irreplaceable and he is gone. I feel the same way about the passenger pigeon.

We can love things and we can lose them. When we hang on too tight to any species, or beloved, or moment in time, we move out of the great flow of infinity, which is God's name for time and space. Death becomes technologized or demonized or idolatrized, as if God didn't also make death.

Once we are part of the great ongoing conversation that Charles Darwin called evolution, once our genes are in the mix, we flow on. Flowing on is so much better than fixing. I'm not "against" de-extinction science. Instead, I am for going with the flow of God's life and death pattern for infinity.

[Donna Schaper is senior minister of Judson Memorial Church in New York City.]

Editor's note: Want more stories from Eco Catholic? We can send you an email alert once a week with the latest. Just go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.