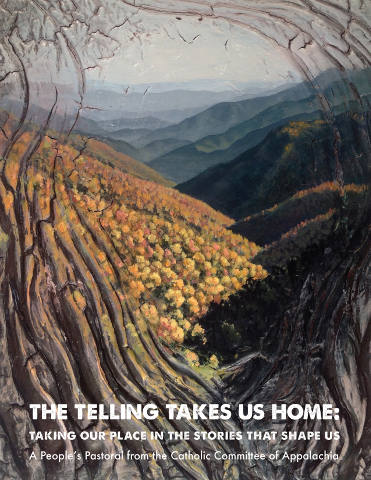

Cover of "The Telling Takes Us Home: Taking Our Place in the Stories that Shape Us," a new pastoral letter from the Catholic Committee of Appalachia. (CNS)

Ron Gulla became an environmentalist after he leased his small farm to a natural gas company in Hickory, Pa. He watched as his water turn yellow and flammable, his vegetation turn black and inedible. He soon met up with other farmers whose calves were born with no eyes and other horrible deformities.

Gulla’s story is one of the many recorded and reflected upon in the past three years by the Catholic Committee of Appalachia (CCA). The listening sessions sought to not only hear, but capture and share the cry of God’s people, and all his creation, in this often-overlooked part of the United States, to give it a public voice with a universal echo.

The fruits of CCA’s work is a final pastoral letter from the people, The Telling Takes Us Home: Taking Our Place in the Stories That Shape Us. The letter represents a cultural encounter with those who are suffering in the Appalachian region: from the environmental ruin of their land by coal, fracking and mountaintop removal; from economic deprivation; from health problems and addiction; and from racial prejudice and sexual discrimination.

Released in late December, the People’s Pastoral is the third such document CCA has published and comes on the 40th anniversary of its first letter, This Land is Home to Me (1975). That document was followed up 20 years later by At Home in the Web of Life (1995).

Like its predecessors, The Telling Takes Us Home flows in a poetic structure. But unlike them, it initiated not from the region’s bishops but from its residents, resulting in a “by-the-people, for-the-people” document. A grassroots letter to the world, it springs from multitude of voices: the land, women, coalfield residents, miners, economically vulnerable communities, the homeless, imprisoned, people of color, and the LGBT community -- all of whom are longing for justice.

“We wanted to listen to the people and places who hurt the most, so that we can create new paths forward, to embody a church that Pope Francis looks to envision,” said Michael Iafrate of Wheeling, W. Va., the document’s primary author and chair of the CCA board.

Nearly four years in its evolution, the pastoral began with CCA volunteers conducting listening sessions and surveys. They gave presentations to Catholic parishes along with other faith communities, secular groups and activist organizations. Volunteers interviewed people in a variety of diverse settings, including prisons and roadside diners. Individuals could also respond on the CCA website.

More: "Pastoral letter ‘from the trenches’ emerging in Appalachia"

Jeannie Kirkhope, CCA coordinator, estimates that nearly 1,000 people weighed in from West Virginia, Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky and Pennsylvania, and even as far away as Michigan. The dialogues and follow-ups will continue on the CCA website, she said.

The Telling Takes Us Home is a microcosm of the current plight of the planetary community. In a way it offers a smoothly transitioned, localized sequel to Pope Francis’ environmental encyclical “Laudato Si’, on Care for Our Common Home,” reading every bit as beautifully and powerfully.

Congregation of Notre Dame Sr. Jackie Hanrahan, one of the listeners in Virginia, explained, “Laudato Si’ is a love letter to everything in creation, and the pastoral represents a small piece of how this can play out in a particular region.”

The People’s Pastoral offers numerous examples. Early on, CCA acknowledges the work it has done in the region and the fruits that have followed the previous letters, all of which has helped its network place itself among those who struggle.

“Still, each of us, in the communities where we find ourselves, must pause and honestly evaluate how we are doing in responding to the call to be a ‘church of the poor.’ Can we really take our place among the excluded, if befriending the poor and marginalized is uncomfortable, if we don’t always like what we hear when we listen to their struggles and ideas, or if we have not begun to understand our own poverty and dependence upon the gifts of God and one another?”

In a section titled “The Magisterium of the Poor and of Earth” the pastoral states, “Official pronouncements and projects have not always helped us to hear these voices. But we remember the deep, Biblical truth that the voice of God does not come from high places and halls of power but rather in the still, small voices of the least of our sisters and brothers.”

It continues later in the document’s second part: “The transformation that Pope Francis envisions happens locally in places and in our relationships with one another as we are knit together as the Body of Christ. This knitting together of peoples, comes from below, happening primarily among movements and communities of struggle, not as a result of the ideas of great leaders imposed from above.”

More: NCR looks at Laudato Si' in coal country: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Throughout the pastoral, a number of stories tell of the anger, grief and deprivation that can emanate from injustice, but two particularly striking ones appear in those of Gulla and a woman in Virginia.

The pastoral describes the scene from Gulla’s back porch as he saw it following the arrival of fracking:

“In his community, water has turned black and become flammable, testing for high levels of contaminants. Livestock have been born sick, blind, and deformed, or have been stillborn, and fish have disappeared or mutated. Truck drivers who transport waste material have experienced rashes, dizziness, migraines, and swelling of the face and limbs. Community members regularly report that their local environmental protection agencies side with the gas companies and do little to protect them.”

After seeing these side effects of fracking, Gulla became more active in environmental circles. Today, he speaks at environmental rallies across the country. Fired from his lucrative job in sales for a large equipment company for talking to customers about fracking, Gulla now works as a health surveyor for a sustainability organization.

When a gas company brochure advertising the monetary advantages of leasing one’s land appeared in his local parish bulletin, Gulla convinced his pastor to stop including the ad. Of the natural gas industry, he told NCR, “They don’t care about this earth, or the sacredness of creation. They only care about the money that’s coming in.”

Belinda Schoke of Rose Hill, Va., a single mother of three, desperately longed to get a good education, but both her family and fundamentalist church were vigorously opposed. Notre Dame Sr. Beth Davies recounts her story in a section titled “The Voices of Women”:

“She lived at home, and her parents, especially her father, resented her participation in college courses. Since she had children, they thought she should be home with them, ‘teaching them the Bible.’ When it came time for finals, her parents forbade her to take them because she had work to do at home. She did as she was told, and one day when her father was clearing land and burning brush in a fire, she made her father proud by burning her school books and papers. After destroying her dreams on that pyre, she went back to the house and cried. Eventually, she left her parents’ house, and their control, and went back to school to become a nurse.”

In a section on “The Voices of Women,” Notre Dame Sr. Beth recounts how Schoke, a young single mother of three, divorced from her alcoholic husband, burned her school books and papers in the backyard after her parents wouldn’t allow her to take final exams for her GED. “Since she had children, her parents thought she should be home with them, teaching them the Bible. After destroying her dreams on that pyre, she went back to the house and cried. Eventually, she left hr parents’ house and their control and went back to school to become a nurse.”

How did she escape? By remarrying the alcoholic husband she previously divorced. “It was the only way,” Schoke told NCR in the phone interview.

She would divorce him again, and return to school for her certified nursing assistant degree. She now works at a senior care center. A bout with cancer slowed her down for a time, but Schoke eventually plans to return to school to become a registered nurse. Now happily engaged to a kind, loving man, Schoke still recalls those repressive days: “I used to wear dresses and never cut my hair. I never wore a pair of slacks till I was 28.”

Schoke said that Davies has introduced her to many wonderful people, whose churches are far different from the one in which she was raised. Reflecting on those prior days, she marveled, “I can’t believe how people can get that messed up by a religion.”

Even the grief-stricken chirp of the Cerulean Warbler finds a place in the chorus of voices heard in the People’s Pastoral. This small endangered bird journeys 3,000 miles each spring from the Andes Mountains to its sister peaks in central Appalachia, its natural habitat more and more under threat.

Janet Keating, executive director of the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition in Huntington, W. Va., listened deeply and imaginatively to one of these little birds, hearing a creature startled and confused about what is happening “to these lush forests, my summer home in the mountains of Central Appalachia.”

“I can’t help but wonder as I witness the death of this mountain and its abundant life, if somewhere my Creator weeps and the human spirit is also diminished. Thankfully, I have faith in steadfast allies who care deeply … they are issuing this call to action which speaks for the marginalized and voiceless ones like me,” the warbler of Keating’s reflection said.

In retelling these stories and more, The Telling Takes Us Home is quick to note “No single explanation or narrative can contain all of the experiences and stories in Appalachia today,” specifically relating to the region’s economic and ecological distress of the past century.

Those stories, it said, have often carried hopeless, apocalyptic themes, of feeling like a “sacrifice zone” where its people and resources are exploited for the benefit of the rich and other parts of the world. While Appalachia “serves as a window” to the suffering places of the world, it too can reveal the hope of a new way of life.

“In order to change the course we are on, we need to change the stories we tell about ourselves, our region, and our place in the whole of creation. Only then can we construct, from below, the new economies and ‘a new way of sharing this planet’ that we need in order to do life differently. More than ever, we need new stories about creation and the purpose of human life, drawn from the best of our wisdom traditions.

“And we in Appalachia, in all of our diversity, must take our place in the story in new ways that help us find liberation from the stories that have thus far often led to death and destruction,” the People’s Pastoral read.

[Sharon Abercrombie is a frequent contributor to Eco Catholic.]

Editor's note: Want more stories from Eco Catholic? We can send you an email alert once a week with the latest. Just go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.