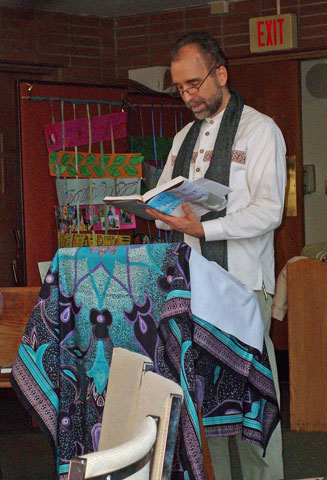

Joe Regotti reads from Scripture during a December liturgy in which 12 new Maryknoll Lay Missioners formalized their commitments to mission. (Eric Cambier)

Editor's note: In the previous issue of NCR, we presented a story on trauma experienced by missioners serving in areas of conflict around the world. In this issue an expert describes a model trauma program for missioners and we look at one particular program.

Trauma is an occupational hazard for missioners serving in conflict zones, such as civil wars, gang violence, acute poverty or natural disasters.

"Missioners in conflict zones will experience either direct trauma (e.g., rape, kidnapping, torture, gun violence) or vicarious trauma (e.g., sleep disorders, burnout, loss of identity, social withdrawal) due to serving people suffering direct trauma or both," said Robert Grant, an expert in trauma who has spent his career teaching, counseling and helping missioners and members of the military from around the world deal with trauma.

For these reasons, missioner training must include trauma training, or what he calls "the missiology of trauma."

"You have to prepare both the bodies and the mind for mission work. ... Sending missioners with trauma into missions with trauma creates double trauma," Grant said. That formation would be sensitive to identifying existing trauma in a person's life.

Once missioners are sent overseas, "there needs to be renewal work in the field," Grant said. He recommends that the sending organization have a "rover," a person who visits the missioner periodically with the primary intent of evaluating him or her and looking for signs of trauma.

For example, missioners suffering from trauma will often self-medicate, either through alcohol or drug use or by becoming a workaholic.

"I would recommend a buddy system for missioners," Grant said. "It's hard sometimes to see the signs of trauma yourself." It is important to "line up local professionals with counseling training," he said. "It takes leg work and resources."

Upon returning to the U.S., many sending organizations -- for example, religious orders -- will send the missioner to a "renewal program," or place the missioner on sabbatical or to a drug and alcohol rehabilitation program. "In these types of programs, often trauma is not addressed," Grant said. "It's a 'hit or miss' kind of thing."

He recommends a re-entry residential program that would allow for debriefing, sharing of stories, individual counseling, exercising, spiritual direction, and psychological assessment.

"Ongoing support groups for missioners contribute to preventative care," Grant said.

Missioners often carry around unresolved grief due to the loss of friends, co-workers, families and children. Grant recommends education related to bereavement and mourning be included in training programs.

Lastly, a key component of missionary life is "developing a missionary spirituality," or "a spirituality around human suffering," Grant said. "The missioner has to go up on the cross and die to who you are and who you were and surrender many assumptions. One has to let go of a lot of things, such as ego … and get closer to God and to your real self. If a missioner can do this, then the missioner begins to grow, to be more authentically and more experientially grounded."

One U.S. Catholic sending organization, Maryknoll Lay Missioners, implements much of what Grant recommends.

The organization has a thorough vetting and discernment process for potential missioners, according to Joe Regotti, director of mission services. Regotti has been a Maryknoll Lay Missioner for 15 years.

The Maryknoll family includes the lay missioners, Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers and Maryknoll Sisters; each branch is entirely separate from the other two. The lay missioners have the most extensive training program for trauma.

Maryknoll Lay Missioners can be as young as 23 to as old as 65 and come from all walks of life; they commit to three-and-a-half years overseas. At any one time, the organization will have some 60 missioners serving in six mission regions of El Salvador, Bolivia, Brazil, Kenya, Tanzania and Cambodia. Consideration is being given to expanding their mission regions farther.

"Maryknoll Lay Missioners is the only organization in the U.S. that makes a lifetime mission vocation possible for lay Catholics," Regotti said.

Once accepted into the program, the missioner attends a 10-week, residential orientation program to prepare them for inculturation into overseas mission. Trauma training is an important part of a missioner's toolkit, Regotti said.

A psychologist facilitates the trauma training, which includes reflections on personal experiences or history of trauma, psycho-education to understand how trauma affects people, understanding the signs of trauma in your own behavior and that of others, and understanding coping strategies once a missioner experiences trauma while on mission.

"Of course the work we do around spirituality, personal prayer, communal prayer is meant to give people a really strong fortification to be able to not just get through three-and-a-half years working with people in extreme poverty, but to really thrive in overseas missions," Regotti said.

Once in-region, the lay missioner undertakes a six-month process of inculturation, language study, and education about the economy, society and the local church. Then they have "three years to get deeply involved in relationships and their ministries in the communities where they will live and serve," Regotti said.

Maryknoll Lay Missioners focus on five areas: pastoral ministry, sustainable development, human and civil rights, health care, and education.

"We are tremendously concerned for the stewardship of our greatest resource, our people," Regotti said.

Each region has a director who acts much as the "rover" Grant described.

"We seek out trusted people [for the missioner] to talk to," Regotti said. The regional directors meet with the missioners at least monthly, if not weekly. "We want our missioners to flourish," he said.

"Isolation, for example, can be a destructive behavior. Seeking out another trusted person or group or speaking with a therapist are steps we will help the missioner take. We try to be intentional about making the missioner feel safe after experiencing trauma."

"Coming home is the hardest part for missioners," said Julie Lupien, executive director of From Mission to Mission, a Longmont, Colo.-based re-entry support organization.

Maryknoll Lay Missioners who have completed their three-and-half-year commitment undergo a two-week Mission Integration Program at the group's headquarters in Ossining, N.Y. The objective is to have the missioners tell their stories to each other in a prayerful, respectful way. "We create a safe space, a confidential space for the missioners to tell their story," Regotti said. The first two days are a spiritual retreat.

"We spend a full-day workshop titled 'Unpacking Trauma,' facilitated by a professional practitioner," he said. "We want the missioner to have a good, healthy way forward to continue to integrate their mission experience."

After this post-mission program, about half of the missioners re-sign contracts for another term while half re-integrate into U.S. society. This latter group enters Maryknoll Lay Missioners' alumni group, "Always a Missioner."

Does all this work on trauma pay off for Maryknoll Lay Missioners?

"Our folks are much better prepared to deal with personal trauma than most people in all of society," Regotti said.

Previous: Trauma: a missioner's occupational hazard

[Tom Gallagher writes NCR's Mission Management column. He recently joined NCR's board of directors. His email address is tom@tomgallagheronline.com.]