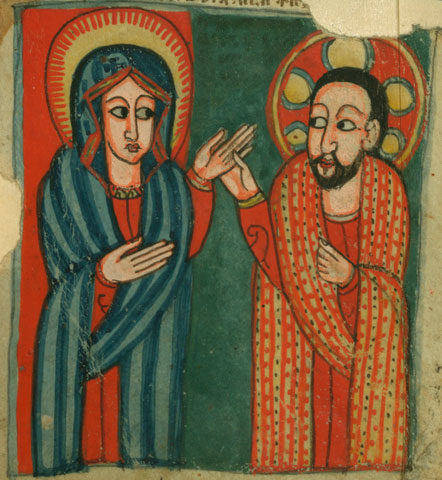

Mary and Jesus are depicted in a 17th-century Ethiopian manuscript (© Walters Art Museum, used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license)

The angel Gabriel tells Mary, "Behold, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you shall name him Jesus."

Joseph might not be Jesus' physical father, but Mary was to be his mother, his physical mother, like mothers from Eve until now. She would conceive in her womb, carry the child in her womb and deliver him from her womb. And I wonder, always, did he resemble her? Did Jesus have his mother's mouth? Her eyes? Her coloring? Could you find a similar cleft in each chin? An unruly lock of hair that no amount of water or combing could tame? Did the neighbors in Nazareth say, "Oh, that's Mary's boy, for sure. Anyone can look at him and tell."

It's one of my favorite parables. For, if Jesus resembled his mother, that meant she resembled him, as well. We hear in Genesis that God created us, man and woman, in the divine image, bearing something of the Creator in our flesh. Perhaps it's the magisterial language -- "Let us make human beings after our image, after our likeness." -- that makes it hard to connect God's being with our own lumpy bodies and lined faces, our own human beings. I understand how my Uncle Dick, as he aged, looked just like his mama, that is, if Mother Curry had been bald and worn a suit, but I have trouble looking in the mirror, or looking in the face of a stranger, and seeing God looking back.

So, in his conception and birth, Jesus does what he will later do with the stories of robbed and beaten travelers and ungrateful sons and housewives searching for lost coins: He takes an example so daily and so plain as to be familiar to every hearer. It may be hard to connect one's own flesh with the One who spoke the world into being, but we can all identify with a mother and son who have the same scattering of freckles across their noses. And we can take the story from there: God looks like us and we look like God. Which means that all human faces bear the holy features.

How, then, shall we live?

I'm thinking of this just now because the feast of the Assumption is upon us, that feast of Jesus' care for his mother's flesh, even in death. At the same time, I'm averting my eyes from televised images of bodies, broken and scattered and left for days on a Ukrainian field. I read of foxes feasting on the dead flesh at night, of human scavengers stealing credit cards and jewelry from the same undefended bodies. And I'm reflecting that if we can see Jesus' face in Mary's own, so we can see it in these bodies. We can, and must, see it in all the bodies: on the beaches of Gaza, in the ruined churches of Mosul, in northern Nigerian villages, at the Texas-Mexico border.

The novelist Graham Greene wrote:

The definition of the Assumption proclaims again the doctrine of our Resurrection, the eternal destiny of each human body. ... The Resurrection of Christ can be regarded as the Resurrection of a God, but the Resurrection of Mary foreshadows the Resurrection of each one of us.

Greene is telling us that the parable is at work even in Mary's death. We can imagine a grand eternal destiny for the God-made-flesh, even as we lament our own decay in the earth. But if the human flesh that bore and held and fed and raised Jesus is also shown exquisite care, then we begin to glimpse our own hope, in ways both concrete and glorious.

But it's not just Mary-and-me. Germanus of Constantinople wrote in the eighth century of Mary's assumption, "Even though you departed, you did not separate yourself from the Christian people. You, leading to incorruptibility, did not distance yourself from this corruptible world."

Mary is singular in sinlessness, but she is never meant to be alone on the road to God. Rather, she is our guide. Like an accomplished mountaineer with a group of novices, she cautions us to "walk where I walk" and to "follow my lead." Her intention is that all of us make the climb and live to summit.

And following her lead, that of She-Who-Follows-the-Christ, means following him. Jesus Christ, whose care is with our bodies. Feeding the hungry crowds who came to hear him, making breakfast for his apostles on another Palestinian beach, healing Peter's mother-in-law and the daughter of a Roman -- and so, enemy -- soldier, weeping over his dead friend, calling Mary into heaven before corruption could touch her lifeless body, Jesus the Christ is never careless or cruel with human beings, their hearts or their bodies.

The gentle disposition of Christ's own ark must be the model for our treatment of each lesser, leaky ark. Even where the breath of God breathed into each one of us, the breath that makes us human, is low and almost exhausted, we look to the parable that is Mary and learn how, then, we shall live.

[Melissa Musick Nussbaum lives in Colorado Springs. Her online column for NCR is at NCRonline.org/blogs/my-table-spread. More of her work can be found at thecatholiccatalogue.com.]