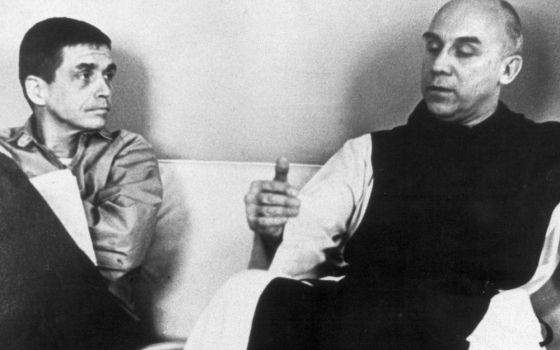

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, right, and actor Martin Sheen, third from right, join the annual School of the Americas protest in 1999 at Fort Benning, Ga. (CNS/Quirin, The Messenger)

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, who died at the end of April, not only challenged the conscience of the Catholic church and the nation on the dangers of militarism and the need to affirm Christ's teachings of nonviolence, he challenged those who oppose war to engage in direct action to stop it.

He was a devout Catholic amid the largely secular anti-war left. He opposed abortion as a form of violence while most of his colleagues in the peace movement identified as "pro-choice." He remained a priest while many of his contemporaries, including his brother Philip, left the priesthood for marriage or over doctrinal disputes. Berrigan was guided not by adherence to a particular ideology, but by a deep faith in God through the nonviolent witness of Jesus Christ.

Over the decades, I prayed with him, broke bread with him, was arrested with him, and discussed matters of politics, theology and movement-building. We did not always agree. Yet his warmth, his humor, his faith, his wisdom and his commitment always left me inspired.

His actions led him to become one of the best-known priests of the 20th century. Yet he had no desire for people to follow him. He simply wanted people to follow the Gospel.

Related: Berrigan's life lesson: fidelity has its payoffs

Like many Americans, I first learned of the Berrigan brothers in 1968 when they and seven other Catholic activists entered the Selective Service office in Catonsvillle, Md., seized hundreds of draft files and, using homemade napalm similar to what was then being dropped on Vietnamese villages, burned them in the parking lot.

In a statement following the incident, the group which became known as the "Catonsville Nine" declared, "We confront the Roman Catholic church, other Christian bodies, and the synagogues of America with their silence and cowardice in the face of our country's crimes. We are convinced that the religious bureaucracy in this country is racist, is an accomplice in this war, and is hostile to the poor."

Traditionally, pacifists have believed that nonviolent action should eschew damage to property. Dorothy Day, for example, thought that the Berrigans' advocacy of property destruction and other militant tactics crossed a dangerous theological threshold.

However, the Berrigans firmly believed that some property -- such as nuclear warheads and draft files -- had no right to exist and it was the responsibility of pacifists to destroy them, as long as people were not harmed. Their actions were intended to shock, as the American people needed to be made aware of the enormous danger from their nation's militarism.

While most activists of that era sentenced to prison for nonviolent resistance would turn themselves in to authorities, Berrigan and his brother, Philip, were willing to go underground, even showing up unannounced to speak at rallies and church services then disappear before they could be arrested. They became folk heroes, appearing on the cover of Time magazine and becoming the first priests to appear on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted list.

At the same time, they never wavered from their opposition to violence, particularly as the Weather Underground and other extremist anti-war groups began a campaign of bombing. In The Village Voice, Berrigan wrote, "The death of a single human is too heavy a price to pay for the vindication of any principle, however sacred."

The first time I met Berrigan was in October 1973 during the Arab-Israeli War, when I was 16 years old, at a talk he gave in Washington, D.C. While many peace activists at that time would avoid the often divisive issue of Israel and Palestine, he decided to address it head on. Unlike many liberals of that era who opposed U.S. militarism but rationalized for Israeli militarism, he could not defend militarism by anybody. His analysis was blunt and he did not try to be "balanced," but it was basically an accurate and honest assessment. In short, it was typical Dan Berrigan.

He noted how Israel was, like the United States and South Africa, "seeking a biblical justification for crimes against humanity." He expressed his regret that "in place of Jewish prophetic vision," Israel had launched "an Orwellian nightmare of double talk, racism, fifth-rate sociological jargon, aimed at proving its racial superiority to the people it has crushed."

Noting the similarities of Israel's "military-industrial complex" with that of the United States, he observed how "Israel has not freed the captives, she has expanded the prison system, perfected her espionage, exported on the world market that expensive blood-ridden commodity, the savage triumph of the technologized West, violence and the tools of violence." He also noted that he "was very depressed by the silence of my own church about Israel."

As with many of his words and actions, giving such a speech at that time was not very strategic, leading to widespread criticisms and misinterpretation. Similarly, his later arrests, largely focused around trespassing at nuclear weapons facilities, which at times included damaging components of warheads and missiles, led to many months in prison without much publicity or a discernible growth in the movement. However, strategic efficacy did not really matter to him. For Berrigan, it was a moral imperative. Indeed, when a reporter noted he was not getting as much attention as he had previously, he replied, "I don't think we ever felt our conscience was tied to the other end of a TV cord."

And yet, while some accused him of acting more out of "Catholic guilt" than on building a movement, Berrigan's witness indeed had a profound impact. It encouraged the broader anti-war movement, which prior to Catonsville had been primarily focused on street protests, into nonviolent direct action and other forms of active resistance. It brought many young Catholics, who had been alienated by the hierarchy's support for the Vietnam War and U.S. militarism, back into active involvement in the church. As a middle-aged priest, his actions brought greater credibility to opponents of the Vietnam War, then often portrayed as angry, young, long-haired misfits.

And he undoubtedly played a role in moving the Catholic church to a more active witness for peace and justice. The church eventually came out against the Vietnam War, renounced the legitimacy of nuclear weapons, and challenged the Israeli occupation and repression of Palestinians.

Indeed, just days before he died, the Vatican hosted a landmark meeting raising questions about the just war doctrine and examining nonviolent alternatives. Would this have even been possible were it not for such prophetic voices as Berrigan?

[Stephen Zunes, a professor of politics and international studies at the University of San Francisco, is currently a visiting professor at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Otago in New Zealand.]