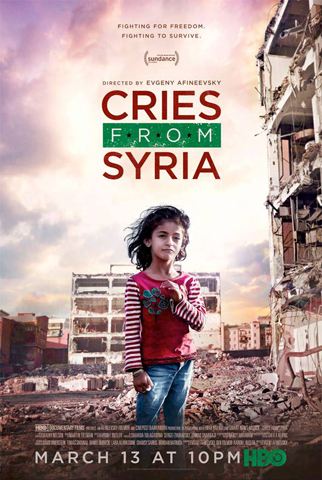

Poster for "Cries from Syria" (criesfromsyria.com)

"Cries from Syria"

Monday, March 13, 2017

9 p.m. CT/10 p.m. ET

The opening scene of "Cries from Syria" is of a 2-year-old baby lying dead on the sea shore, the rippled waves washing over him, because the boat bringing him to Europe capsized. This new HBO Documentary film (it premiered at Sundance in January) by Oscar- and Emmy-nominated director Evgeny Afineevsky, premieres tonight on television. The tragedy of the Assad regime's oppression and genocide is guaranteed to shock even an audience habituated to graphic war violence on television, and in film and video games. The reason is because what Afineevsky shows us is real, much of it footage taken from cell phones of those who witnessed the atrocities.

The story is told in an uncomplicated, linear way, so we can follow the story and understand. The narration is from women — sisters and mothers, orphaned children and some men who have managed to escape to Turkey or other refugee camps, or even to Germany. Then, towards the end of the hour-and-51-minute film, we hear from Syrian Army generals who have defected over the killings of civilians, and tens of thousands of children — Syria's future.

The brutality of Assad's almost systematic attacks province by province on those who called for freedom from his oppressive government is astounding. How is it that the world has stood by and not responded to the estimated 600,000 dead? After viewing this film you will want to take action, from prayer to giving to aid organizations, to contacting your senators and representatives. One can only hope that Assad, Putin, President Trump and members of Congress will watch as well.

Beginning with the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011, some young people spray-painted their calls called for the fall of Assad on the walls of a school in the city of Daraa: "It's your turn Doctor" (Assad trained as an ophthalmologist in the UK). The male students were hunted down and cut down or imprisoned by the Syrian Army. In the next city a man tells of a young man — who practiced nonviolence by handing out flowers taped to bottles of water to the soldiers as he led protests — who was imprisoned, tortured and dismembered and killed.

As the film progresses, chapter by chapter, the audience comes to understand the basics of the war including the collusion and cooperation of Russia with Assad in bombing all the hospitals in cities held by any other group but the Syrian army. Assad defines the rebels as germs, as viruses, and the only way to get rid of them is by using chemicals. So he used the only chemical not mentioned in any agreements with the West: chlorine. You cannot imagine what chlorine can do to a baby but you will see it here.

In a recent trip to the Middle East I encountered a noncombatant member of the Syrian Army in a public place. He approached me because I was a sister and he wanted to tell me that he was the only Christian, a Catholic, in his unit. I asked him about what was going on in Syria, the suffering, the war. He looked at me quizzically and shook his head. "It's not true," he said.

This film would beg to differ.

The role of the White Helmets (whose heroic actions to save victims from the unrelenting bombings was chronicled in an Oscar-winning documentary) is shown, one rescuer breaking down when he pulls a little girl out of the rubble, barely breathing. Members of the White Helmet rescuers were not allowed to attend the Oscar ceremony due to the travel ban.

Then the film details how ISIS infiltrated the freedom forces, as they helped at first but then began recruiting children and using brutality to train them and even greater brutality to control the people.

In 2014, I interviewed filmmaker and writer Sebastian Junger when his documentary film Korengal (his second about the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan and its impact on soldiers) was released. I asked him if he was a pacifist. He had been a journalist during U.S. involvement in Serbia in the 1990s and indicated that it was a very different war than the one in Afghanistan. He told me that his definition of a just war was one that "relieves suffering." If that is the litmus test for military involvement then something must be done to stop the suffering in Syria. It's not about winning; it's about saving lives by stopping the violence.

Set your DVR or watch "Cries from Syria" when it is broadcast tonight. The conflict may be complicated, but the brutality and gore of the killings of hundreds of thousands for the sake of one man, Assad, while the world watches, is not. It's inhumane, desperate, heartbreaking.

"Those who don't do battle," one young man says, who, like so many others is willing to fight to the death for freedom from oppression, "cry."

Over 7 million people have been displaced because of the war in Syria; of these 2.5 million are children.

A new song by Cher, "Prayers for this World," backed up by the voices of children in Los Angeles, closes out the film. The image of the dead baby on the shore is there again at the end of the film. A rescue worker runs to gather him up and take him from the camera's view.

We need to see the little boy so we that we are morally and emotionally afflicted in our living rooms. So that we understand the cost of our comfort.

[Sr. Rose Pacatte, a member of the Daughters of St. Paul, is the Director of the Pauline Center for Media Studies in Los Angeles.]

[Graphic content in trailers below.]