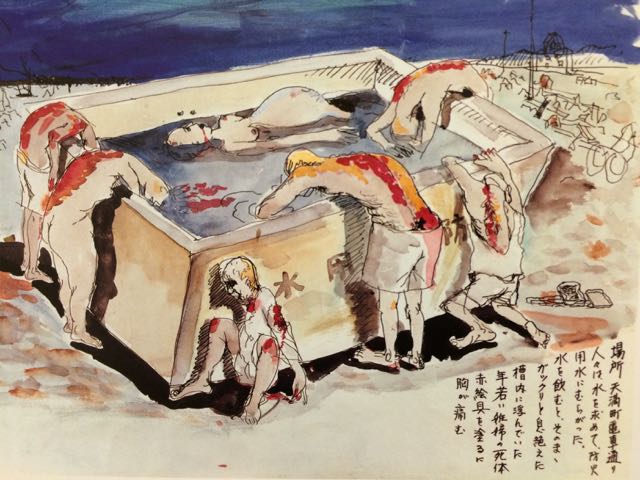

Child's depiction of Hiroshima attack from KC exhibit (Photos by Tom Fox)

This is a sobering week. I find myself pondering the fact I was alive -- age one year, six months, 24 days -- the day the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, at 8:15 in the morning.

Aug. 6th to Aug. 9th, the period between the first atomic bomb used in war and the second, over Nagasaki, is a second Triduum to many of us who make the link between the Crucifixion of 2,000 years ago and the one we continue to experience today as we reflect back 70 years to those three days of war which took 200,000 lives in Japan.

Both Tridua force deep reflection on human failure and sin; both stir somber thought and prayer.

Unlike the Triduum in our church’s liturgical calendar, the Hiroshima/Nagasaki Triduum does not yet end in resurrection and hope. Where we find hope is in the thought that some people gather together each year across the world to encourage each other to continue to work for a world without nuclear weapons.

Last night my wife and I joined of few of these vigilant peace-seekers. We attended the opening ceremony of the “Hiroshima/Nagasaki: Seventy Years Beyond the Bombings” exhibit at the UMKC Miller Nichols Library here in Kansas City. This haunting exhibit of books, posters and photos shared by the Hiroshima Peace museum runs through October and drew several dozen peace activists last night to a low-key opening ceremony.

That only a relative few showed to open the exhibit speaks to the collective distraction we face as a nation today, a distraction that allows evil to breed and grow; at the same time the fact that a dedicated group of longtime peace seekers organized the exhibit and have remained faithful to the lonely task of drawing attention to the mounting dangers of nuclear weapons is a sign of hope that madness will not have the final word.

Part of the Kansas City exhibit includes evocative drawings by then young survivors (hibakusha) who depicted their experiences in crayon and ink. The exhibit is simple, extending along one hallway near a room full of computers. Those who passed in front of the posters spoke in low voices, often cupping their chips, shaking their heads slowly in efforts to give postulate meaning to human madness. The images: entirely flattened and burnt out cities, shadows of bodies burned onto sidewalks and walls, flesh hanging from hapless survivors, a cowboy-hat-wearing American bomb builder posing with an atomic bomb between his legs.

The exhibit reception was graced with platters of small cookies baked by a local Japanese woman. Mercedarian Missionaries Sister Filo Hirota, a Japanese native in town to visit her congregation, spent time huddled with exhibit organizer Jane Stoever, longtime local peace advocate and Catholic Worker.

The day before, Hirota visited NCR’s Kansas City office and participated in a short ceremony. The read reflections on the bombings written by hibakusha.

I have traveled to Hiroshima twice, at age 19, as college student, and 43, as a young father. On my second visit I accompanied my two older children, Daniel and Christine.

This week, as we commemorate seven decades since the bombings, it is sobering to recall that no treaty is in place requiring the world’s nuclear-weapons-holding nations to reduce the sizes of their arsenals. Meanwhile, these nations are spending billions (the U.S. is spending $1 trillion over the next ten years) “modernizing” their weapons and delivery systems.

The bomb the U.S. dropped over Hiroshima had a blast force of 12 kilotons of TNT; it flatted five square miles. The nuclear bombs sitting upon the tips of missiles on U.S. Trident submarines, by comparison, have a blast force of 475 kilotons of TNT, 60 times larger. Should one of these be used -- just one -- it could burn a swath covering much of the planet, sending into space a cloud of radioactive dust that would circle the earth for months, or longer, causing far wider death.

Just as the Incarnation continues to take place today; so, too, does the Crucifixion, most vividly in the madness that is the nuclear arms race to global immolation.