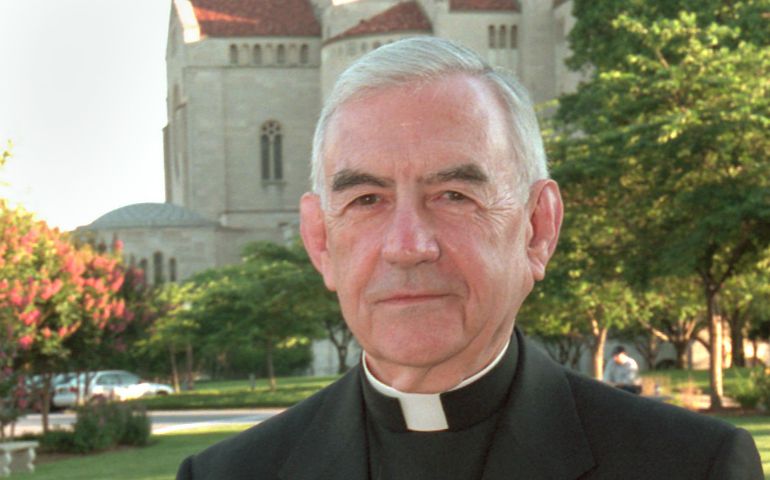

Retired San Francisco Archbishop John R. Quinn is pictured in a 2001 photo in Washington. He died June 22 at age 88 in San Francisco. He headed the Northern California Archdiocese from 1977 until 1995. (CNS photo/Nancy Wiechec)

John R. Quinn didn't need mitres, titles, tokens of authority to add to his stature. It was in his prior nature to be Christian. That charismatic center expressed itself through his priesthood, scholarship and archbishop's role in San Francisco, but those marks of faith would have in my estimation arisen in whatever state he might have found himself. In his understanding, priesthood was a vocation he'd received, and therein he became a luminary of heart, mind and spirit.

Among the finest illustrations of those gifts was his navigation through the rough waters of a Vatican investigation of American sisters in the early 1980s. It was a fraught gesture by Pope John Paul II at a time of growing tensions between the vigorous post-Vatican II renewal of sisters' traditions and the increasing fear of their uncontrolled rebellion among top officials in Rome. Archbishop Quinn was picked to conduct what was portrayed as a look at why sisters' vocations were dropping, but it was widely suspected as a measure to quell the sisters' newly exercised freedom to do what the council had given them permission to do.

The breakout revision of convent life had caused both exuberance and resentment. By the time the pope ordered the investigation (officially called a more benignly sounding "study") on Nov. 15, 1983, the conflict between the Vatican and the sisters had clearly worsened. Mercy Sr. Theresa Kane had created a storm during John Paul's visit to the U.S. by appealing directly to him to open all ordained offices to women, and the major organization of sisters' communities caused a backlash by inserting the word "leadership" in their conference name. The word implied woman religious had rights to guide their own affairs, which contrasted with the traditional subordination of all their authority to male clerics. The sisters had stuck to their position, and their group was indeed renamed "The Leadership Conference of Women Religious." That and other assertive steps had been steadily labeled disloyal, individualistic and "secular." Four years from the start of stepped-up advances, sisters found a warrant for investigation at their collective doorstep.

Into the breach stepped Archbishop Quinn, a representative of what many sisters saw as the main source of the push-back. Calmly, attentively, respectfully, he listened to the sisters openly and even sympathetically, knowing at the same time that he was under mandate to promise no relief or reform. Given the highly-charged circumstances, Quinn's performance was beyond diplomatic. Without conveying illusions or darkly warning of reprisals, he struck a realistic accord and vowed to relay the sisters' concerns and resolve to his bosses.

Presentation Sr. Margaret Cafferty, then the executive director of LCWR, spoke for the trust Quinn had instilled among the conferees, calling him "the best friend we could have had." In other, hard-liner hands, she added, it could have been an utter disaster.

The archbishop made good on his promise to deliver the sisters' discontent. He reported "a decline in respect for the Pope and the Magisterium of the Church" which evoked "certain tensions … between some religious and the Holy See." He included a ringing appeal for improved treatment of women both in society and the church, noting that many Catholic women chafed at being excluded from "policy and decision-making roles in the church." He linked this exclusion to the drop in vocations. "In light of this [lack of] potential, candidates find other modes of service and hesitate to enter religious life."

It was the strongest statement of support for the sister's renewal initiative by a bishop before or since. Years later, Rome's efforts to suppress what traditional clerics contended were dangerous reforms had shown no signs of letting up. Strategies to contain or reverse the direction of renewal continued be employed, blunting further development while not nullifying its council impetus. By the end of the first decade of the next century, a more comprehensive pair of investigations aimed more pungently to quash "disloyal" elements.

Had greater openness and insight followed Archbishop Quinn's careful study, the path forward might have been harmonious and mutually enhancing. Though that wasn't to be, the archbishop's gifts of perception, compassion and spirit brought signs of hope in that brief moment.

[Ken Briggs reported on religion for Newsday and The New York Times, has contributed articles to many publications, written four books and is an instructor at Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania.]