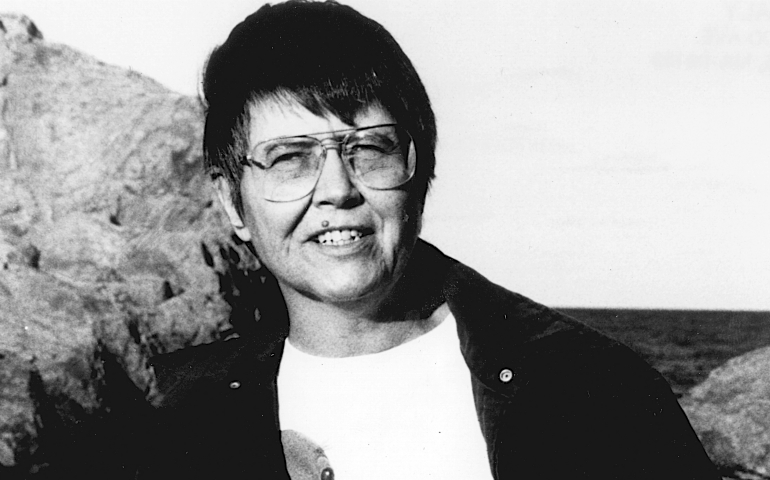

Mary Daly in 1987 (Gail Bryan)

Editor's note: "Take and Read" is a weekly blog that features a different contributor's reflections on a specific book that changed their lives. Good books, as blog co-editors Congregation of St. Agnes Sr. Dianne Bergant and Michael Daley say, "can inspire, affirm, challenge, change, even disturb."

Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism

by Mary Daly

Beacon Press, 1978

In the late 1970s, the feminist movement was in full flower in the church and society. The first women were ("irregularly") ordained to the Episcopal priesthood in 1974 (made "regular" in 1976). The first Roman Catholic Women's Ordination Conference was held in Detroit in 1975. And, in the winter of 1977, the Vatican issued Inter Insigniores, declaring its "inability" to ordain women because women lacked a "natural resemblance" to the male Jesus.

At the University of Chicago Divinity School, where I began graduate studies in 1975, women students were in the minority, but we had begun to find our voices. Some of the more advanced students organized a Women's Caucus. I eagerly joined them.

I was a product of women's education and strong women role models. Unlike many women my age, and even younger, I had had quite a few women teachers in high school. Nearly all of my religion professors in my women's college were women (religious) with doctorates. My mother and grandmother both worked to help support their families when it was clear that my grandfather's or father's paychecks would not cover all the bills, at times when this was decidedly out of the ordinary. The Religious of the Sacred Heart, who ran my high school and college, placed a high value on educating girls and women. They and I never doubted my ability to accomplish what I had set out to do.

After college, I worked for a few years in an investment banking firm in New York, and was the assistant to one of the first women portfolio managers. She and the other (male) portfolio manager I worked for considered it their responsibility to train me to move up, gave me additional responsibilities and both encouraged me to get my Master of Business Administration.

When I announced that I was going to the University of Chicago, they were delighted, until I told them that I would be studying across the quad from the business school. Even then, they were encouraging and said they would welcome me back as a business ethicist, although my own path led me elsewhere. It would seem that I was a born-and-raised feminist (or "women's libber," as we called ourselves then) who knew what sexism was.

But at one of the first Divinity School Women's Caucus meetings, I came to realize how much I was influenced by patriarchal society. A group of a dozen or so women, we went around the room, saying a bit about ourselves and responding to the inevitable question a graduate student is asked: What do you want to write your dissertation on?

I can't recall all the answers, although I do remember the late (and great) Nancy Hardesty sharing her work on women and American Protestantism. When it came to me, I remember saying something like "I am interested in feminist theology, but I really want to write on systematic theology."

There may have been a collective gasp in the room — there should have been. I left the meeting wondering whether my idea that I was interested in women's issues but what I really wanted to work on was the "real stuff" of theology needed to be re-examined.

I went about the business of a graduate student in theology, studying the history of Christian thought (Origen, Augustine, Anselm, Aquinas, Scotus, Luther, Calvin, Schleiermacher, etc.) and contemporary theology (Moltmann, Niebuhr, Rahner, Gadamer) under some of the school's great scholars: David Tracy, Brian Gerrish, Langdon Gilkey, Bernard McGinn and Paul Ricoeur. Anne Carr had joined the faculty the same year I came as a master's student. I took her course on Rahner, the theologian on whom she had written her dissertation. Yes, women's issues were interesting and important, but first I needed to learn (real) theology.

Then, sometime in 1978, my friend Anne Patrick gave me a copy of Mary Daly's Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism. Anne had been asked to write a short review for a journal. She had a full plate of other things to work on, so she asked me if I was interested. I agreed.

I was familiar with Daly's The Church and the Second Sex, which made a strong but "balanced" (i.e., nonthreatening) argument for the full inclusion of women in all of the church's ministries. I also knew about Beyond God the Father and the famous "walkout" at the Harvard Chapel. But nothing had prepared me for Gyn/Ecology.

Perhaps because I was taught to try and enter the mind of the author with empathy, I did not immediately respond to Daly, as many of my undergraduate students have, with shock, horror and, especially, denial to her many charges: that Christianity is inherently necrophilic because it worships a dead man on a dead tree, that Shel Silverstein's classic children's book The Giving Tree is really about how men destroy women with their greed and selfishness, that American gynecology and psychiatry need to be understood in the same category as the burning of witches, Chinese foot-binding, Indian suttee and African genital mutilation.

Rather, in reading Daly, I began to realize that the religion and culture in which I had been raised — even as a privileged, upper-middle class white woman from the suburbs — were profoundly, deeply and utterly riddled with sexism.

I read Daly's book not so much as a literal description of reality but as a radical exercise in the implications of misogyny. I remember sitting in my apartment with the book, feeling as if my head had been taken off my neck, turned upside down, completely shaken up and put back on. Everything I had been taught to believe was challenged: the tradition I was studying, the church that I had been raised in, the society that had even given me so many opportunities – all of them were infected, riddled with the sin of sexism.

I did not then and do not now go as far as Daly did in her critique — that is, by finding all institutional religions hopelessly patriarchal and destructive to women. And I appreciate the Audre Lorde's and others' critiques of Daly's descriptions of African, Indian and Chinese traditions as culturally imperialistic and insensitive. Nevertheless, Daly devastatingly exposed the slimy underbelly of religion's treatment of women over the centuries and its present implications. For me, there was no turning back to an innocent or even "balanced" understanding of women and religion.

Feminist theology was just emerging in the late 1970s. After reading Daly, I began to read everything on the topic I could get my hands on. And although I did not write my dissertation on an explicitly feminist topic — on the connections between Catholic theologies of revelation and theological aesthetics — I soon came to see how this topic had many feminist implications. My Madeleva Lecture and book, For the Beauty of the Earth, drew out some of them.

A year or so after I read Daly, I was preparing for my first teaching job, and was assigned two introductory courses in theology and one course of my own choosing. When I told my new department chair that I wanted to teach a course on women and religion, he protested that I was hired to teach systematic theology. I asked Carr what I should say in response, and she said, "Tell him that feminist theology is systematic theology: It asks what difference it makes if women as well as men are taken into consideration." I remembered my own words from a few years before and I credit Daly's book with helping to move me toward this point.

Many years later, I had the opportunity to talk with Daly. I was co-editing an issue of Concilium on the topic of women's voices in world religions and I had written her to ask if she would contribute a short article. She wanted to talk about it and so we did. At one point, she asked how I could survive being a faculty member at a Jesuit university, and I responded by saying that if she could, I could too! We both laughed. Although she declined to contribute, I valued her candor and thanked her for her contributing to my own growth in feminism.

Daly is difficult to teach to undergraduates. Her radicalism can turn off students who have never been exposed to feminist ideas. Students learn that she excluded men from her classes since she wanted her women students to feel free to speak. Even though I explain that she would meet with male students separately, for many she seems to embody all of the stereotypes of the man-hating feminist. Her brilliant and often wickedly humorous twists on redefining words, her refusal to bend to convention, and her laser-like focus on every kind of injustice to women can alienate students who are wary of feminist ideas that sound "angry."

But without righteous anger, there would be no feminism. Thomas Aquinas famously argues that if one is not angered by injustice, there is something wrong. And Daly, with her classical education, would agree. Daly taught me that one cannot smooth over or excuse misogyny, that it must be exposed and named, and that one must use everything in one's power — one's intelligence, wit and, yes, anger — to overcome it.

On occasion, I have found myself labeled a "radical feminist." I am sure that Daly, were she still with us today, would object. I have spent my entire teaching career of more than 35 years in colleges and universities run by religious orders of men. I have learned to get along with them, to befriend some of them, to watch my language, to make compromises. I insist that my students not reject theologians solely because of their views on women.

But sexism and misogyny still exist. Religions still have not done enough to condemn them. And powerful statements against these sins are needed more than ever. Daly's central role in the development of feminist theology cannot be overstated, and I for one am grateful that she had the courage to be radical and to inspire me.

[Susan A. Ross is a professor of theology at Loyola University Chicago and a past president of the Catholic Theological Society of America.]