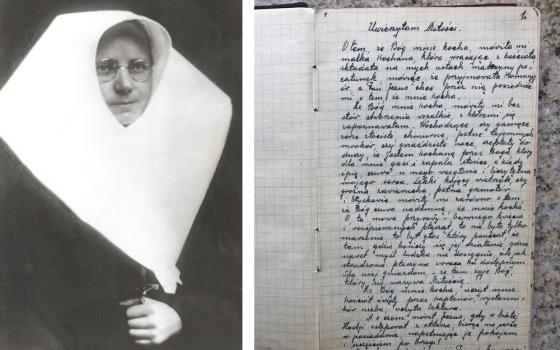

Teresa, 36, and her daughter Norma, 17, discuss their work as “mother monitors” with Catholic Relief Services' SEGAMIL program in Guatemala. (Robert Christian)

Last week, President Donald Trump ordered a crackdown on unauthorized immigration, the construction of a border wall with Mexico, and a more aggressive deportation policy, in addition to placing new restrictions on the entry of refugees. Trump's policies have triggered large demonstrations across the county.

Bishop Joe Vásquez of Austin, Texas, has said that when contemplating immigration issues, we have to see the "human face of the reality of what is going on." Many of those protesting Trump's policies have seen this "human face" in their own communities.

I gained some additional insight into the human impact of migration and the viability of efforts to deter it on a recent trip to Guatemala, in addition to examining the underlying causes of why hundreds of thousands of people — including tens of thousands of unaccompanied children — have left their homes and risked violence, degradation and more on the dangerous trek to the United States in the past few years.

In 2014, President Barack Obama identified this situation as a "humanitarian crisis." In that fiscal year, the number of migrants from Central America outnumbered those from Mexico for the first time. Of the 408,870 apprehensions at the U.S. border this past year, a larger number once again came from Central America.

While the conditions in Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador are not identical, examining the immediate and underlying causes of migration from Central America's Northern Triangle is essential to identifying how this humanitarian crisis might end and why ill-conceived nationalistic policies are likely to exacerbate rather than mitigate the crisis.

In Guatemala, along with the other fellows who were awarded Catholic Relief Services' 2016 Egan journalism fellowships, I spoke with Guatemalan Foreign Minister Carlos Raul Morales. Morales argued that from 2000 through the present, economic factors have driven migration from Guatemala. He was quick to say that this does not mean that security factors are immaterial, but he noted that problems with gang violence and drug cartels are more severe in Honduras and El Salvador.

Morales highlighted economic inequality, discrimination against the indigenous population, and a lack of opportunity as the source of widespread poverty. Roughly 60 percent of the population lives below the poverty level.

"People are literally dying of hunger," he said, adding that the nation's biggest problem is that roughly half of all children are malnourished. He emphasized the social and physiological impact of this malnutrition on both the child and the county's future. For those who are illiterate or very poorly educated, he argued that there are three basic options: to become a field worker, to join a gang or to migrate.

Morales acknowledged that the state has not done enough to invest in people and provide social programs that adequately address malnutrition and the other conditions that inhibit development. Concurrent with this problem is an absence of adequate infrastructure. Many live in homes with dirt floors and without indoor plumbing, which can foster serious health problems.

Progress on addressing corruption

To address these matters, Morales emphasized the need for shared responsibility from all sectors. But the prospects for achieving this are daunting. Government corruption has been widespread. The government also has inadequate revenue from taxes, the lowest in Latin America as a percent of gross domestic product.

In addition to trying to maximize profits, business owners are reluctant to pay taxes to a government that wastes or steals the revenue. They also frequently have to pay extortion to gangs or other criminal organizations to stay in business and physically safe. Many employ private security, Morales said, rather than relying on the police, but their caution makes sense given the security situation and past government behavior. At the same time, many powerful private sector firms have been complicit in corruption.

But progress on addressing corruption has been made. Last year, President Otto Pérez Molina and Vice President Roxana Baldetti were removed from office and charged with crimes for their role in an illegal financing, embezzlement and money-laundering scheme. This followed the mobilization of a broad coalition of Guatemalans against endemic corruption. The United Nations has provided assistance in anti-corruption efforts with the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala. The current attorney general is also developing a strong anti-corruption reputation.

The new government seems to be generating some hope in Guatemala City, particularly among middle-class professionals, that the nation has turned a corner and that brighter days are ahead in terms of reducing government corruption. But in the countryside, where unemployment and underemployment are high and opportunities are limited, no one with whom I spoke shared that optimism.

Morales laid out four keys to addressing the large-scale migration from Guatemala:

- Reducing extreme poverty;

- Creating jobs;

- Improving security;

- Strengthening institutions and the rule of law.

He called for a better police force, good teachers, better hospitals, and an end to the spoils system in which government employees are hired as political favors. He also expressed disappointment over the high percentage of funding in the $750 million Alliance for Prosperity plan that is for earmarked for security.

Morales is correct that lack of development and widespread poverty are at the core of the migration crisis, the key underlying factor and an immediate cause for many. It also facilitates the drug trade and strengthens organized crime, which are behind much of the country's violence and insecurity. Economic inequality fosters corruption by oligarchic elites. The lack of security and government corruption, in turn, hinder development and perpetuate poverty.

It remains to be seen if civil society and government mechanisms are strong enough to provide the type of transparency that is essential to good governance. Morales also declined to discuss whether the gross inequalities in wealth can be addressed without altering the distribution of land ownership, a highly contentious issue. But he did acknowledge that no solution will come overnight.

Improving the lives of everyday Guatemalans

The role of nongovernmental organizations and other civil society institutions is critical to both addressing widespread, systemic injustice and directly improving the lives of everyday Guatemalans, even as this injustice persists.

As we traveled across the country, we saw organizations and individuals who, working with local partners, were doing precisely that. The Barbara Ford Peace Center in Santa Cruz del Quiché helps at-risk young people, from ages 16-25, to develop life skills, technical skills, and lessons on entrepreneurship with the goals of education reinsertion, formal employment, or entrepreneurship.

But nothing stands out more than the center's work on family reconciliation. I spoke with a 20-year-old woman named Marta Garcia, who faced a difficult time when her grandfather died, slipping into alcohol abuse and even considering taking her own life. But in this five-month program, she not only learned cooking skills that she hopes to apply in opening up a restaurant; she also regained a sense of worth. She learned to value her mother, with whom she now has a strong relationship.

The center's approach is focused on integral human development and driven by the passionate dynamism of Charity Sr. Virginia Searing. Searing highlighted the lingering trauma inflicted by the Guatemalan civil war and the mass atrocities perpetrated in the area, particularly the fraying of family bonds. She notes, "Every single child experiences secondary trauma."

These problems are compounded by the absence of jobs, which leads many to migrate to the city or out of the country, and presence of the drug trade and gangs.

Tom Tecun, an 18-year-old who participated in the program, stated that gangs were trying to recruit him. His relationship with his family was what led him to reject that path and participate in the program to attain specialized knowledge to try to lift his family out of poverty.

The program cannot address the larger structural problems that make life difficult for many living in the area, but they help young people develop hope and resiliency, improve their relationships with their families, and develop skills that can offer greater economic security.

Another program that is directly improving the lives of Guatemalans is Catholic Relief Services' SEGAMIL food security and nutrition program, which is funded by USAID and, working with local partners, gives mothers courses on hygiene, cooking and savings. In Santa Ana, Momostenango, the impact of the program was demonstrated clearly.

Participants described diversifying their crops, moving from growing corn alone to radishes, celery, lima beans, onions, fruit and more. They showed a system to collect rainwater, an alternative to the often dirty, contaminated water they had relied on previously. The program teaches simple things like the importance of washing one's hands and changing clothes. The program also provides rice, beans and other staples in exchange for attending meetings to learn about nutrition and hygiene.

Improvements in nutrition and hygiene not only improve the health of children, they foster overall development and save lives.

Some of the women in the program travel to other mothers' homes as "mother monitors" to provide instructions. They explain malnutrition and signs that it may present among their children. They weigh children, tell them to get medicine when needed, and teach them nutritional information. They also teach pregnant women about reducing risks to their pregnancy and about the importance of prenatal pills, along with instructions on breastfeeding and changing diapers and baby clothes.

Such programs will not radically transform the country and upend the structural injustice that is behind the migration crisis. But they are radically changing the lives of these families. Since larger injustices will take decades to address, this life-transforming and life-saving work merits continued support and investment.

[Robert Christian is the editor of Millennial. He is a doctoral candidate in politics at The Catholic University of America and a graduate fellow at the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies.]