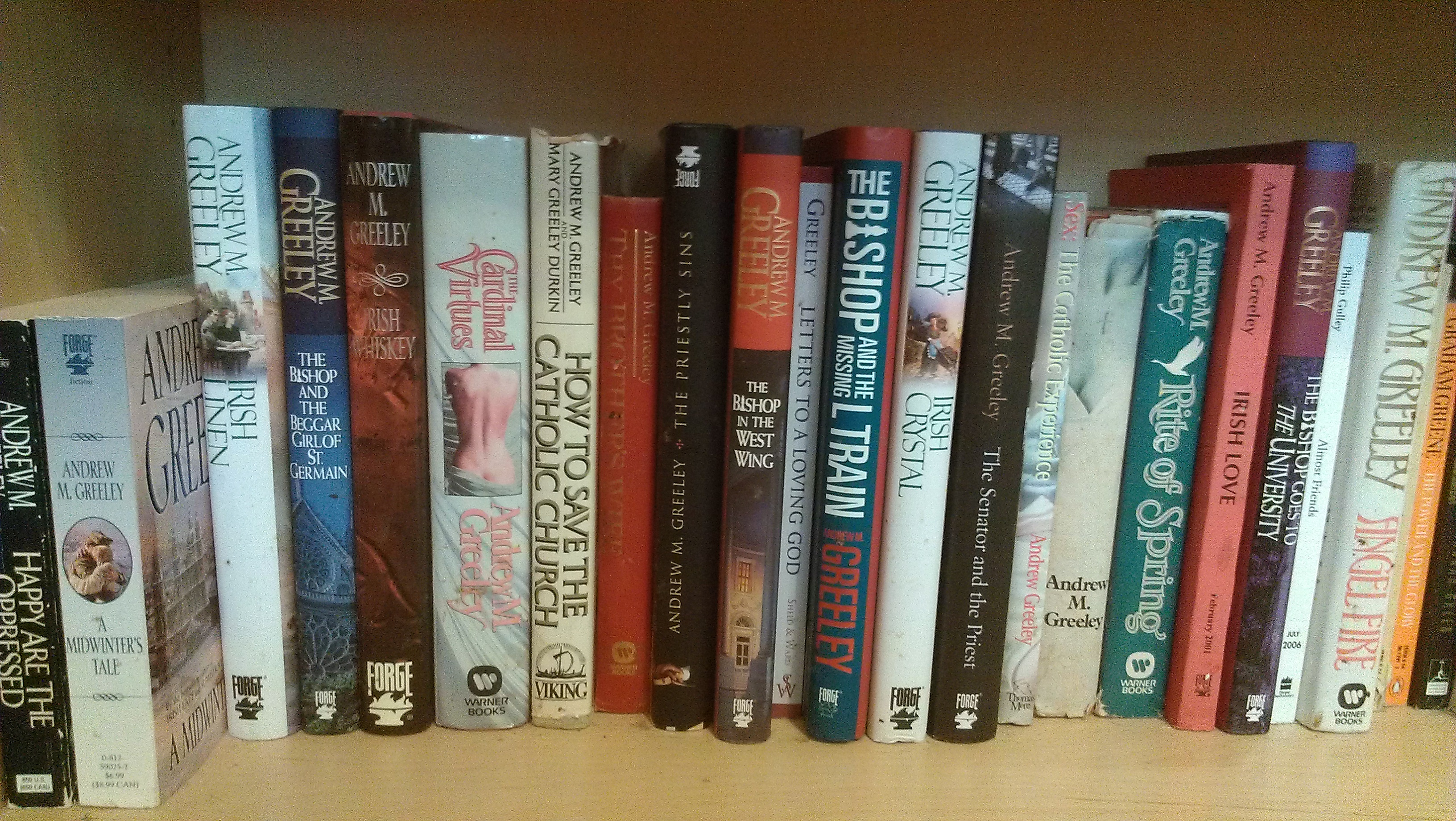

The Andrew Greeley section of my bookshelf.

I’m not sure I’ve ever admitted this before, but Andrew Greeley is the reason I am a Chicagoan—and a Catholic journalist. Although the priest-novelist-sociologist had been out of the Chicago Catholic scene since his accident in 2008, the city and the church lost a great man when he died yesterday at the age of 85.

While I have little to add to John Allen’s excellent obituary, and I suspect that other NCR columnists, such as Eugene Kennedy, Bob McClory, and Mike Leach, have longer and more extensive memories of Greeley than I do, I still wanted to take a moment to remember a priest who had such an effect on my life.

I read my first Andrew Greeley novel while a features reporter at a newspaper in a Los Angeles suburb. While I’d always had a spiritual bent, I had never considered covering religion as a beat. The portrayal of Chicago church politics in The Cardinal Sins helped me realize that religion could be an exciting and meaningful specialization for a journalist.

After devouring every novel he had written thus far, I knew I wanted to move to Chicago and become a religion journalist. Greeley’s love of Chicago was contagious, as was his love for Chicago Catholics, despite his criticism of some in the church hierarchy.

It was in 1996, as a staff writer for the Chicago archdiocesan newspaper, The New World, that I first met Greeley in person. I was writing a feature on his latest novel, White Smoke, about the church politics surrounding a papal election after the death of a character clearly modeled on Pope John Paul II.

A little nervous to be meeting the famous author, I took a seat in his office with the book, press kit and notebook on my lap. Before I could ask my first question, he asked me one: What did I think of the book?

I was honest, explaining how I loved the plot about church politics, but found the love story—between a New York Times reporter and his ex-wife, a CNN correspondent—less satisfying, especially since I was myself going through a separation from my husband. He praised me for obviously having read the book, as I’m sure many an interviewer on that book tour had not.

Later, I would contrast Greeley’s lack of response to the self-disclosure about my separation with that of one of his colleagues, Msgr. Jack Egan, another famous Chicago priest. I was interviewing Egan for the second time when he noticed I was no longer wearing a wedding ring. His response to my news included compassionate listening and the sharing of his home phone number should I ever need to talk.

Greeley was not that pastoral friend to me, though I know he was to others. Still, his written words continued to inspire me, even as I began to tire of the repetitiveness of his fiction. Greeley’s nonfiction essays, published often in U.S. Catholic, where I later worked as an editor, contained much wisdom and were accessible to everyday Catholics. Whether defending the laity’s right to the sacraments or marveling at the spiritual importance of beauty, Greeley clearly had a deep connection to God and to the church.

Those who saw him merely as a complaining liberal mischaracterize Greeley. Still, like any good Chicagoan, he knew the importance of politics, whether secular or sacred. In my 1996 interview about White Smoke, he described the problems of a centralized bureaucracy in Rome. “I think the big problem in the church now is that the pope reigns, but he doesn’t rule,” he told me.

Although the traumatic brain injury from his accident prevented him from ever writing again, friends, including the Rev. Martin E. Marty, say he was occasionally lucid. (Marty, like Greeley and the late Patty Crowley, has a place in Chicago’s John Hancock Tower. Marty also shared a birthday with Greeley, Feb. 5, 1928.)

In White Smoke, it’s clear Greeley was pulling for the new pope to be a character based on Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, the Jesuit some saw as papabile before he died in 2012. I’d like to think that, having lived to see the election of a new pope who might “rule rather than reign,” Greeley decided it was OK to finally let go and go home to God.