Editor's note: "Take and Read" is a weekly blog that features a different contributor's reflections on a specific book that changed their lives. Good books, as blog co-editors Congregation of St. Agnes Sr. Dianne Bergant and Michael Daley say, "can inspire, affirm, challenge, change, even disturb."

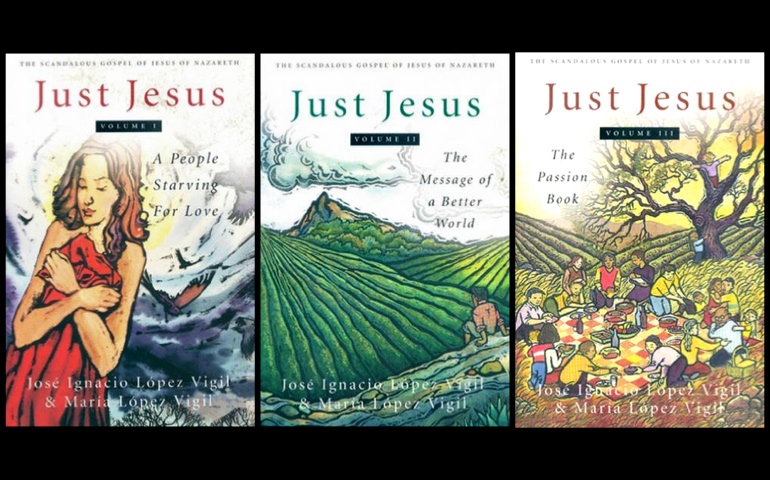

Just Jesus (three volumes)

by José Ignacio López Vigil and María López Vigil

(Crossroad, 2000)

During my second year of college, one of our religion assignments was to read a life of Christ and then write a review. I looked through the shelves and found a number that looked interesting. On the shelves were Giuseppe Ricciotti's The Life of Christ (1947), Fulton Sheen's Life of Christ (1958), the three volumes of L. C. Fillion's The Life of Christ: A Historical, Critical, and Apologetic Exposition (1928-29), and Ferdinand Prat's two volumes Jesus Christ: His Life, His Teaching, and His Work (1950). To be honest, I cannot recall whether I chose Fillion or Prat to read and review. I may have done both.

I also discovered Romano Guardini's The Lord (1954), with its stunning Rouault painting on the dust jacket. I read it, slowly, over the course of a year. The butcher at our local grocery store had already read it several times and urged me to give it a try (a memory I cherish). Fillion and Prat struck me as more academic and scholarly, while Guardini was more reflective and existential.

The book that eventually caught my imagination, however, was Alban Goodier's two-volume The Public Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ: An Interpretation (1936). I was a first-year novice and had just finished making the Spiritual Exercises. Each evening we had a half-hour devoted to reading the life of a saint or a life of Christ. That's when I discovered Goodier. I loved it. I must have read it three or four times before moving on to his volume on the Passion.

Over the years, I've taught courses on Jesus. I have a number of favorite writers, especially James Dunn, John Meier, Jon Sobrino and N.T. Wright. For the past several years in my introductory class, as well as in courses for the permanent diaconate program, I have used José Pagola's Jesus: An Historical Approximation. It is superb.

Yet the book that made the deepest and most lasting impression on me originated as a series of radio broadcasts south of our border — 144 broadcasts, to be exact. The scripts plus commentary appeared in 1982 as Un tal Jesús: La Buena Noticia contada al Pueblo de América Latina. The two volumes of Un tal Jesús were eventually translated and published, first in the Philippines under the title A Certain Jesus and then, thanks to Crossroad, in three volumes as Just Jesus.

Each volume opens with three forewords: one from an editor of Claretian Publications for the Philippines edition, one from Ignacio Ellacuría, and one from me. I was stunned to see that my remarks followed Ellacuría—an association that I treasure, even though our paths were very different.

Un tal Jesús was not written as a life of Christ, but as a retelling of familiar Gospel scenes in a way that is fresh and imaginative. The humanness of Jesus is foregrounded thoroughly and consistently. He is humorous, compassionate, outgoing, prophetic. He possesses a relationship with God that is remarkably (yet not unbelievably) intimate, profound — and that seems to be growing as his mission unfolds.

I have reread and replayed the story of the healing of the leper (Mark 1:40-45) countless times, and each time, by the end, my eyes are moist. Jesus and John (the disciple narrating each of the episodes) go to visit the leper's cave (the man has a name, a family, and before the onset of his disease, worked as a fisherman in Simon's village) in order to bring some food that Simon's wife had prepared. While John is urging caution, the leper appears. Desperate and lonely, Caleb cries at one point that the place is so forsaken that not even God would ever pass this way.

Drawing close, Jesus asks him to show them his sores. As Caleb unwinds the cloths, he discovers that the sores have gone.

John exclaims, "What have you done to him, Jesus?"

To which Jesus answers, hesitantly, "But, John, I ..." No sense of magic there, but a subtle move toward mystery. The Jesus unafraid of desolate places lures the imagination.

The context of this retelling of the Gospel is thoroughly Latin American. The idiom, the culture, the food, the ordinariness of village life, with its gossip and petty rivalries, the hard work in fields or fishing the lake, the voices of children and of the ancients — all of that seems so much like the village life that is woven into the narrative world of the Gospels themselves.

But what drives the story forward is Jesus' vision of the reign of God. And that reign is first and foremost a reign of justice. And why does justice figure into the story so prominently? Because another feature of the Latin reality is 500 years of oppression, from the arrival of the conquistadores to the emergence of the dictatorships. More than anything else, that reality draws the tightest connection between the two worlds: Israel under the foot of the Roman Empire, and the historical experience of the peoples of Central and South America under the feet of powerful international political and economic interests — the enduring empire of capitalism.

For me, it's all about imagination. The Gospel lives within us through image and story, scenes to which we become present over and over again. I cannot go back to Goodier because biblical scholarship has advanced so much, and, in time, Un tal Jesús will feel dated as well. Yet what has tied me to it is 20 years of traveling to the Andean region of Bolivia and the same number of years of speaking with and listening to people close by from Guatemala, Mexico and Ecuador.

Essentially, I guess, I am a storyteller, less obviously in the classroom than in church; but a storyteller nonetheless. Images become the vehicle for opening minds and hearts, and for communicating the deepest truths about the human world. Teaching theology is essentially the cultivation of imagination. All that we believe ultimately derives from narratives, both the many narratives that make up the biblical tradition and, increasingly, the countless local narratives that provide form and identity to peoples throughout history.

In the past few years, I have been teaching a course called Defense Against the Dark Arts; the class is about theology and imagination. The idea arose because several of our majors (knowing my affection for the Harry Potter series) asked if I would offer a course on J.K. Rowling. Before too long, I realized that practically no student I've taught in recent memory had read the whole of the New Testament, whereas some have read the Harry Potter series eight or more times! One student confided to the class that she read the books so many times because it was a world she could retreat to; others chimed in.

How, I wondered, could imaginations become just as much at home in the Gospel story as in the world of Hogwarts? And I continue to wonder. But what has become clear is that the ultimate defense against the Dark Arts — the many "spells" and unseen forces that paralyze and destroy us through fear — is imagination, because imagination is the place where hope resides and fears are tamed.

Just Jesus, then, opens a space for imagination. But unlike a work of fantasy, Just Jesus connected to the world of my pastoral experience and the way I had come to read the Gospels. Three times, over the course of nine months, I read the books and listened to the episodes with people from the Hispanic community. Each time, the response was enthusiastic and (for me) gratifying. It seemed sometimes that we were making an annotated retreat together as Gospel scenes came alive; or, perhaps more precisely, as the humanity of Jesus became increasingly real.

Just Jesus sensitizes the imagination to discover mystery in the ordinary: an imagination that feels more at home with the church as a field hospital (to draw on an image that Pope Francis likes), with a Jesus who was comfortable living with Simon and his family, who worked, who wept and who laughed, and who brought the divine presence even into the most desolate places.

In his foreword, Ignacio Ellacuría notes that those who are accustomed to viewing Jesus "from this side of his resurrection and ascension into heaven" may find the Risen Jesus less scandalous than the Crucified One. It is the humanity of the Crucified One — the Palestinian Jesus — that Just Jesus foregrounds.

I think, though, that we are now safely beyond the theological quarrels about the historical versus the divine Jesus that we witnessed in the years following the Second Vatican Council and the debates about liberation theology. This has happened not just because we have retrieved the connection between Easter and the cross (after all, it was the crucified one who was raised), but especially because we have reconnected the cross with the prophetic ministry that led up to it. And that prophetic ministry was squarely centered on the poor, for whom the church has made a fundamental option.

"Just Jesus does not try to replace the Gospels," Ignacio wrote, "but shows how these should be read, deepened and lived."

I would add that it also helps to create the imaginative landscape for truly evangelical prayer and practice. For when we really listen to them, the Gospel narratives infuse our imagination with hope. Without that, the church would be without prophets; and we would be a people who have forgotten how to dream.

[Jesuit Fr. William Reiser is professor and chair of the Religious Studies Department at the College of the Holy Cross. Each semester he offers the course Understanding Jesus, which introduces students to a close reading of Mark's Gospel. This led to his book Jesus in Solidarity With His People: A Theologian Looks at Mark.]