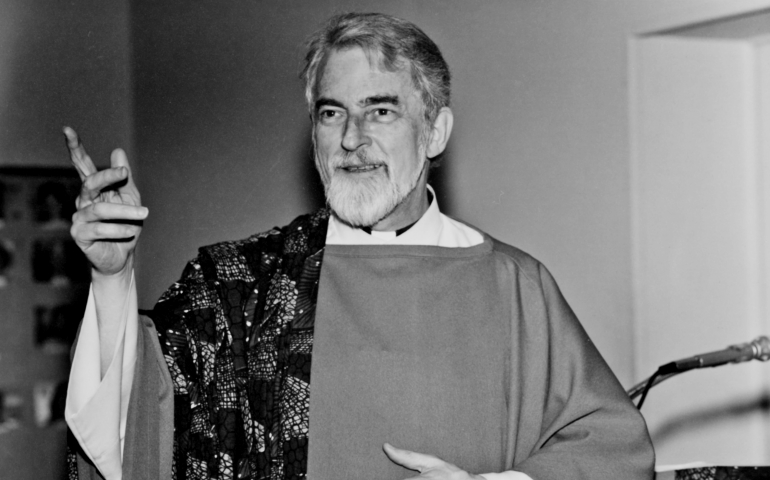

Spiritan Fr. James Healy in 1994 (NCR file photo)

Through the power of modern technology, Frank Finamore has resurrected the words and stories of a spiritual mentor and pastor who died 20 years ago.

The homilies of Spiritan Fr. James Healy, who died in 1997 at the age of 62, are as vibrant today as when they were first uttered, in large part because of the priest's passion for the Gospel and social justice, Finamore told NCR.

A website run by Finamore contains the homilies of Healy, former pastor of Our Lady Queen of Peace Parish, a historically African-American parish in Arlington, Virginia. Through Healy's 12 years there, the congregation expanded to include Latinos, pacifists and workers from the nearby Pentagon. All came away with something from Healy's homiletic insights.

Finamore, who now lives in Nova Scotia, gathered old tapes of the homilies and posts them on FatherHealy.com, each one pertinent to the Sunday readings. That way, former parishioners and others can use the homilies for reflection each weekend.

The focus is on the Gospel and on social justice issues, such as the right to water, Central America, and the treatment of immigrants and refugees — issues that, if anything, are more poignant today than they were when the homilies were spoken back in the 1990s.

"He was a gifted liturgist. He was passionate. And it comes through," said Finamore.

"The meaning of the Gospel is the same. That is when it's really timeless, seeing the roots in the Gospel in how we are supposed to respond," he said.

Healy, 35 years a priest, worked as a missionary in Tanzania, came home and lobbied for Haitian development. He was known as an involved priest. Confronted by a judge who questioned how much assistance he could render to a parishioner at a court hearing, Healy went to law school. He worked steadfastly for affordable housing while a pastor in Arlington. One Sunday, he urged the congregation to read a lengthy New Yorker article on atrocities in El Salvador, admonishing them to take the time, even if it meant needing to skip Mass the next Sunday.

Mercy Sr. Mary Healy, now retired in West Hartford, Connecticut, formerly served as a clinical social worker in Washington, D.C., and regularly attended her brother's liturgies. During homilies, she would occasionally give him the cut sign from the pews, a gesture he would often ignore as he rambled on.

Her brother's passion for justice was nurtured in their family life. They were among 13 children of Michael William Healy and the former Elizabeth Cecelia Coughlin, who operated a tavern and grill in hardscrabble Bridgeport, Connecticut. Michael's business card advertised the place as the longest bar in town.

On their honeymoon in 1916 in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, the couple was enjoying a meal in a hotel restaurant, when a party of African-Americans was denied entrance. Michael registered a protest and the couple left the hotel.

When men down on their luck came to their bar and grill and said they needed a place to stay, their home was opened.

Sr. Healy said that reflection upon the years growing up became staples of her brother's homilies. Of the 13 children, four became priests and two became religious sisters.

"He wasn't a theologian. He was a minister who spoke strongly about the implication of the Gospel in today's world," she said.

Fr. James Healy identified with the history of his Arlington parish, founded by black Catholics who were confined to the back pews of neighboring white churches. That tradition sensitized the community to other groups being left out. When the bishop of Arlington at the time said there were to be no girl altar servers, Healy responded by eliminating altar servers entirely.

His relations with the traditional Arlington Diocese were occasionally testy in his life, and became even more so as he approached death. Healy told his parishioners that he suffered from emphysema and needed to retire from active ministry.

That was not the truth, however. Healy had AIDS, a secret he revealed at a World AIDS Day service at a local Unitarian church soon before he died and in an article he wrote for the National Catholic Reporter. His condition was also described in a Washington Post article.

Some parishioners at the time were disappointed that their pastor delayed telling the truth. Finamore said he wasn't bothered by it, and accompanied his spiritual mentor for a doctor's visit. The priest had a pile of pill bottles he had neglected to use.

"He was sick and he was still more concerned about the lack of affordable housing in Arlington," recalled Finamore. "His focus was on others. I am saddened by the focus on how he died rather than on how he lived."

That's one of the positive developments of the website devoted to Healy, said Finamore.

"Even though he's been gone 20 years, there's value in extending his ministry beyond his life," he said. The proof is in the voice from old tapes from decades-ago Sundays now over the internet, weaving family anecdotes with pointed remarks on injustice in the world and how Jesus might respond. Finamore believes it is a historic treasure worth sharing.

[Peter Feuerherd is a correspondent for NCR's Field Hospital series on parish life and is a professor of journalism at St. John's University, New York.]

We can send you an email alert every time The Field Hospital is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.