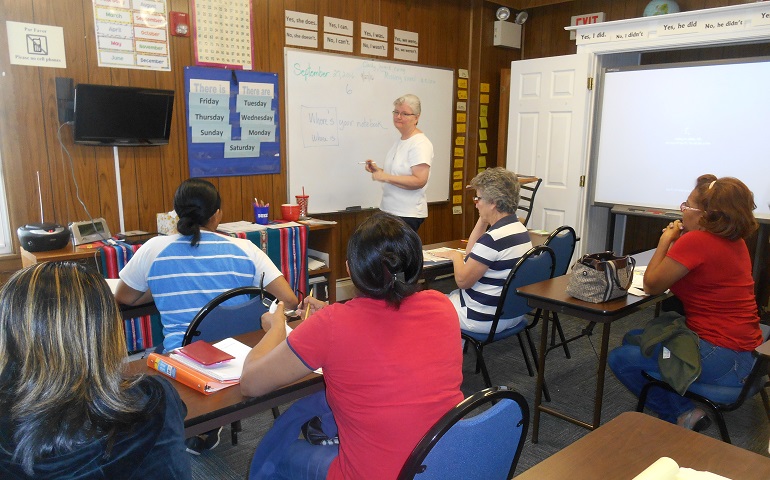

St. Joseph Sr. Patricia Madden teaches an English-language class at the Sisters of St. Joseph Welcome Center in Philadelphia. (Mercedes Gallese)

An Albanian, a Guatemalan and a Moroccan walk into a classroom.

Sounds like the beginning of a joke, but at the Sisters of St. Joseph Welcome Center here in the Kensington neighborhood, it's a daily reality.

"There's a real community formed here," St. Joseph Sr. Connie Trainor, director of the center for the past three years, told NCR. They may come from disparate places, but the immigrants who attend English and citizenship classes get more than just information. They get a start on life in America.

For nearly 14 years, the Sisters of St. Joseph have run the center, located at a former funeral home on Allegheny Avenue, which cuts through one of Philadelphia's more gritty neighborhoods. It began as a conscious effort of the sisters to do something for the people living in severe poverty. They also wanted to respond to parish closings and mergers in Philadelphia, which gave the impression to some that the church was abandoning the inner city.

It was a natural for the sisters, belonging to a teaching community, to focus on education of immigrants. Four of them live above the store.

The sisters' work, seen on an early fall weekday morning, involves a regular routine of classes, sometimes three at the same time. The diverse community learns about English usage, with one class learning about the nuances of speaking contractions in American-style English. Other classes are offered in citizenship training and art, among other subjects.

While providing a reporter a tour of the facility, Trainor describes stories of gritty determination and triumph she sees on a regular basis.

There's the Salvadoran woman who, during the civil war there, was kept in a cave by guerrilla forces, and is still traumatized by the experience. She failed her first citizenship test, then another, until finally succeeding.

"The day she passed, you would have thought there was a new pope," as the word spread around the center’s community, said Trainor. The Salvadoran immigrant took the oath of citizenship in September, a ritual that is a moment of triumph for students and their teachers.

While some politicians proclaim a desire to wall them out, immigrant stories tell a different tale at the center, offering insights into why hundreds of thousands in the world today are on the move.

Trainor regularly hears from immigrants from Honduras, who as children are sent by their parents on the long and dangerous trek up north. The presence of recruiting drug gangs sends a shiver of fear through many Honduran families.

"The parents send the kids here. It's either that or die," said Trainor.

Nancy Bordewick, an immigration counselor at the center, guides students through the byzantine naturalization process, which can take up to a decade for some.

The center offers "a safe place for people, a place where they can be a part of a community. We provide family for those who don't have," she said.

One who found a safe place at the Welcome Center is Rosa Murcia García, who came here from Guatemala eight years ago, undocumented and with little English facility. Now she has her papers and is employed at the center. Of her three children, two are in college and one is in a parochial school.

Murcia Garcia provides counseling from a practical viewpoint.

"I know what they have been through. I understand what they need," she said.

St. Joseph Sr. Patricia Madden teaches and does publicity for the center. Her community's conscious effort to work among the poor 14 years ago has turned into a bigger project than the sisters envisioned. Originally, the project was a literacy van that roamed through the city's parishes, providing adult education classes. When the funeral home was offered for sale, the sisters gobbled it up. Today, the project is expanding for more classroom space, annexing an adjoining row house purchased by the community.

Madden said the Welcome Center is more than just an ESL site.

"The friends they make here are more important," she said, noting that the students learn English and through that get connected to each other. Two women, one from Guatemala and another from Morocco, attended class together and subsequently went into business together, operating a thrift shop.

St. Joseph Sr. Marian Behrle, who works on the center's finances, said it is supported through the Sisters of St. Joseph, fees for students (which are waived for hardship cases), and fundraisers, including an annual Trivia Night at a local tavern (the goal is not so much raising money but building a long-term supportive community). Volunteer teachers and others come from local parishes and a group of students from St. Joseph's University, a Jesuit college just outside the city.

"This is Catholic social teaching in operation," said Behrle, noting that the center follows in the long tradition of the Catholic school system, founded to educate immigrants.

Today's poorer immigrants cluster around neighborhoods like Kensington, a low-rent district that strikes fear into the hearts of some Philadelphians because of its reputation for crime. Sometimes it's necessary to strike alliances with the street people to assure that students and staff are safe coming out of night classes and waiting for buses.

Mary Szurgot, a St. Joseph's University senior majoring in chemical biology, has been volunteering at the center since her freshman year.

"I learned not to be judgmental," she said, about the stereotypes in some quarters about immigrants seeking an easy life. One immigrant would start work at 5 a.m. at a construction site and end up at night taking a bus to class at the Welcome Center. He never missed a session.

Another immigrant student was diagnosed with breast cancer. "That was terrifying. This is hard for anyone to go through. And she couldn't understand what the doctors were telling her."

Beth McNamee, campus minister at St. Joseph's, said the student volunteers from the university find working with immigrants a way to put human faces on a social and political issue, while living out their Gospel commitment.

"It's important for our students to meet people facing these struggles, to learn to reflect upon what I am called as a person of faith to do," McNamee said.

[Peter Feuerherd is a correspondent for NCR's Field Hospital series on parish life and a professor of journalism at St. John's University, New York.]

We can send you an email alert every time The Field Hospital is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.