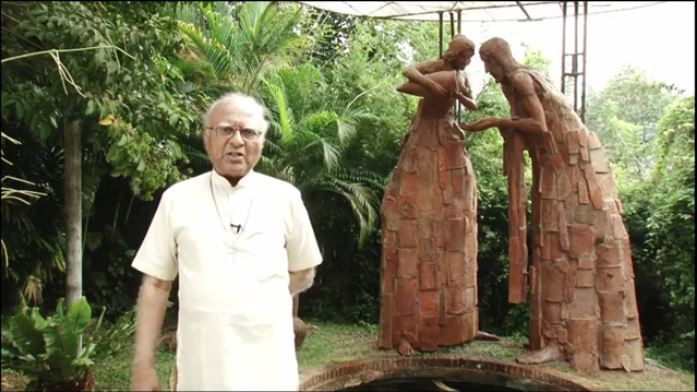

(Clip from a Monastic Interreligious Dialogue video of Jesuit Fr. Aloysius Pieris talking about Buddhist depictions of Jesus and Mary published on YouTube)

Editor's note: "Take and Read" is a weekly blog that features a different contributor's reflections on a specific book that changed their lives. Good books, as blog co-editors Congregation of St. Agnes Sr. Dianne Bergant and Michael Daley say, "can inspire, affirm, challenge, change, even disturb."

An Asian Theology of Liberation

by Aloysius Pieris, SJ

(Orbis Books, 1988)

For Asians who did graduate studies in theology at Roman pontifical universities in the decade after the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) Aloysius Pieris' book, first published in German [Theologie der Befreiung in Asien: Christentum im Kontext der Armut und der Religionen, Herder, 1986] and two years later in English [An Asian Theology of Liberation, Orbis Books, 1988] was, for me at least, an intellectual bombshell.

When I did my theology at the Pontificio Ateneo Salesiano, later upgraded to Universitas Pontificia Salesiana, in Rome in 1968-1972, the reform of theological studies mandated by the council was beginning to be implemented. However, very few of the professors, who had been trained in neo-scholastic Thomism, were willing or able to embark upon it. All classes were done in lecture format; students were provided with mimeographed copies of the professor's lectures, which made attendance unnecessary; and the material for the only test in the course, a half-hour oral examination at the end of the semester, was based on these dispense, as these texts were called. The overriding goal of the theological curriculum was to inculcate the truths of faith as had been taught by the Bible and tradition, and students were graded on their ability to accurately expound on them. For the degree of licenza, which then required four years of full-time study and qualified its holder to teach in a seminary or a pontifical school, a written comprehensive examination on over a hundred "theses," appropriately called de universis (about everything), and a tesina (small thesis) were required. Creativity and critical thinking were discouraged; orthodoxy and fidelity to the magisterium were highly prized.

In terms of theological orientation, the curriculum was largely based on the teaching of the hierarchical magisterium, papal and conciliar. Rarely were primary sources themselves, for example, the writings of Augustine and Aquinas, read; rather students learned about their theologies through the professors' summaries. Among contemporary theologians, only Europeans, such as Henri de Lubac, Jean Daniélou, Yves Congar, Marie-Dominique Chenu, Karl Rahner, Edward Schillebeeckx and Hans Küng (though, curiously, not Hans Urs von Balthasar or Joseph Ratzinger) were considered. Rarely, if ever, was mention made of Latin American theology, even after the landmark meeting of the Conference of Latin American Bishops in Medellin, Colombia, in 1968, and the emergence of liberation theology. Needless to say, African and Asian theologians did not even appear on the theological radar. In short, there was only one kind of theology, namely, the European, and it was regarded as contextually free, culturally universal, and permanently valid.

I mentioned this theological background to help readers understand why my encounter with Pieris' book was a mind- and life-changing experience. Right after completing my licenza in 1972, I returned to South Vietnam, and it soon became painfully clear to me that the theology I had imbibed in Rome was worse than useless for my ministry, especially as chaplain to the only prison for women in the country at the time. Since there were neither opportunity nor resources (nor, I must admit, interest) for theological research, I could not follow the theological developments in Asia. After I came to the United States as a refugee in 1975, I left pastoral ministry to teach theology, frankly, not as a mystical quest for eternal verities, but as a job to support my family.

My earliest scholarly interests were Orthodox theology of the icon, patristics, and Karl Rahner's theology. Later, in the course of teaching and research, I became acquainted first with Latin American liberation theology, and then with Asian liberation theology. In connection with the latter I began researching the history of Christian missions in Asia and Asian theologies, especially the teaching of the Federation of Asian Bishops' Conferences (FABC). It was then that I "discovered" Aloysius Pieris, and my theological horizon expanded, with Pieris serving as inspiration and guide. I first read An Asian Theology of Liberation in 1991 and then Love Meets Wisdom: A Christian Experience of Buddhism (Orbis Books, 1988), and Fire & Water: Basic Issues in Asian Buddhism and Christianity (Orbis Books, 1996).

Like first love, however, it was the reading of Pieris' first book An Asian Liberation Theology that made a lasting and profound impact on my understanding and practice of theology. The German title of his book expresses better than its English one the four aspects of Pieris' influence on me: Befreiung (liberation), Christentum im Kontext (Christianity in context), Armut (poverty), and Religionen (religions). First, liberation, not intellectual contemplation, is the goal of theology. Second, the context of the local church determines the method and themes of theology. Third, the social context of Asian Christianity is systemic poverty. Fourth, the religious context of Asian Christianity is religious plurality/pluralism. Interestingly, An Asian Theology of Liberation is not an organically planned monograph. Rather it is a collection of nine previously published essays, and happily it is a slim volume -- a mere 139 pages -- and highly readable. The essays are grouped around its central theme, namely liberation, and divided into three parts: "Poverty and Liberation," "Religion and Poverty," and "Theology of Liberation in Asia." Clearly, the core concern of Asian theology is liberation, and the two areas in which it is to be achieved are poverty and religion.

The first lesson I learned from Pieris, one that is so obvious as not at first sight worthy of mention, is that theology is inescapably context-dependent. But imagine how intellectually destabilizing this simple truth is for someone, like me, and especially for those who have vested interests in defending it, schooled in the Roman theology that presented itself -- implicitly at least -- as contextually free, culturally universal, and permanently valid. It takes humility and truthfulness to acknowledge the essential situatedness -- read: limitedness, partiality, bias, incompleteness, provisionality -- of all theologies, including the self-proclaimed authoritative ("authentic") teaching of the "ordinary magisterium" and even papal ex cathedra definitions, the infallible pronouncements of ecumenical councils, and the "definitive teaching" of the "universal episcopal magisterium."

This acknowledgment of the essential contextuality of all church teachings and theologies -- Christentum im Kontext -- rejects both the "dictatorship of relativism" and the "dictatorship of absolutism," which are unacknowledged ideological cousins. On the one hand, by recognizing that one's truth is but one way of knowing what is true, one rejects the relativistic claim that there is no truth as self-contradictory, since at least the proposition that "there is no truth" is assumed as categorically true. On the other hand, recognizing that one's truth is but one way among many of knowing what is true requires the abandonment of the well-nigh irresistible temptation of intellectual absolutism, imperialism and colonialism in claiming that one's "truth" is the only truth.

If the context of Christianity specifies the approach and themes of its theology, how can the distinctive context of Asia be discovered? Here lies the second lesson I learned from Pieris, namely, the necessity of the social-political-economic analysis for theology. Of course, Latin American liberation theologians have long practiced this type of social analysis in order to unmask the root causes of systemic poverty in their continent. But Pieris' insistence on its necessity for theology is highly significant, and this is for two reasons. First, the use of social analysis in Latin American liberation theology had been condemned by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, then Prefect of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, in his Instruction On Certain Aspects of Liberation Theology (1984) as of Marxist provenance, and hence contrary to the Christian faith. That Pieris insists on its necessity for Asian theology is a direct challenge to Ratzinger's understanding of how theology should be done. Secondly, Pieris, while appreciative of Latin American liberation theology, argues that social analysis is necessary but insufficient for Asia. Given Asia's religiousness, another analysis is required in order to understand the indispensable role of religion, both "cosmic" and "metacosmic" -- that is, popular and organized -- religion for liberation.

The third insight I learned from Pieris is his characterization of the Asian context as marked by widespread poverty and deep religiousness. Of course Asia is extremely complex -- even the use of "Asia" is contested -- and any shorthand description of it can easily be challenged. But for theological purposes, Pieris' thumbnail sketch of the Asian context is as good as any. What is most significant is that from this twofold characteristic he derives the double task for Asian Christianity, and by extension, Asian theologians, which he terms the "double baptism," namely "the Calvary of Asian poverty" and "the Jordan of Asian religion." As mentioned earlier, this double baptism forms the core of An Asian Theology of Liberation. Without this simultaneous baptism into poverty and religiousness there can be no Asian liberation theology at all, and furthermore, and this is Pieris' astounding claim, no Christian theology sic et simpliciter.

Note that Pieris insists on the necessity of both baptisms at the same time and asserts that this double baptism constitutes the "primordial experience of liberation" given by Jesus of Nazareth, which the church's "collective memory" (Pieris' term for Bible and tradition), mediates throughout the ages, and which theologians must constantly reinterpret for their contemporaries in dialogue with popular ("cosmic") religiosity, the collective memory of other ("metacosmic") religions, for the sake of liberation. The baptism on the Calvary of poverty is undergone by being voluntarily poor ("option to be poor") and by working for the poor ("option for the poor"). Without the former, theology is but an academic exercise for the leisurely elite class; without the latter, theology is but an irrelevant and sterile theoria ("contemplation"). The baptism in the Jordan of religion requires that theology in Asia be done in collaboration and dialogue with believers of other religions to find "homologues" (not parallel, much less identical concepts) for a common religious idiom to express the primordial experience of liberation. Theology, for Pieris, is not primarily fides quaerens intellectum (faith in search of understanding), a favorite definition of theology in the West, but fides promovens justitiam (faith promoting justice) or fides promovens liberationem (faith promoting liberation). Liberation of whom and from what? For Pieris, liberation of the rich from their riches (without detachment from which through voluntary poverty it is impossible to enter the reign of God), of the poor from their enforced poverty (which is enslaving oppression), and of both from "greed" (the worship of Mammon).

I must confess that doing theology the way Pieris recommends and does is hard. Hard in two senses. First, academically rigorous. Pieris never tires of insisting on the necessity of mastering the scholarly tools and linguistic skills to do theology properly. He leads by example: besides being fluent in several European and Asian languages, he has mastered classical languages such as Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, and Pali. Secondly, spiritual discipline. Theology is spirituality and vice versa spirituality is theology. No wonder that I for one will ever remain a beginner or novice in the Pierisian school, and a deeply grateful one.

A bibliographical note: Of the many books by Pieris I have chosen An Asian Theology of Liberation as one of the most influential books for my theological development. Pieris has authored some 20 books and hundreds of articles, most of which are published in Asia and not widely available in the West. Readers who want to understand Pieris' theology more fully, I most strongly recommend his The Genesis of an Asian Theology of Liberation: An Autobiographical Excursus on the Art of Theologizing in Asia (2013). All of his books are available from Tulana Research Centre for Encounter and Dialogue, 521/2 Kohalwila Rd., Gonowala, Kelaniya, Sri Lanka (info@tulana.com).

[Peter Phan is the Ellacuria Chair of Catholic Social Thought at Georgetown University.]