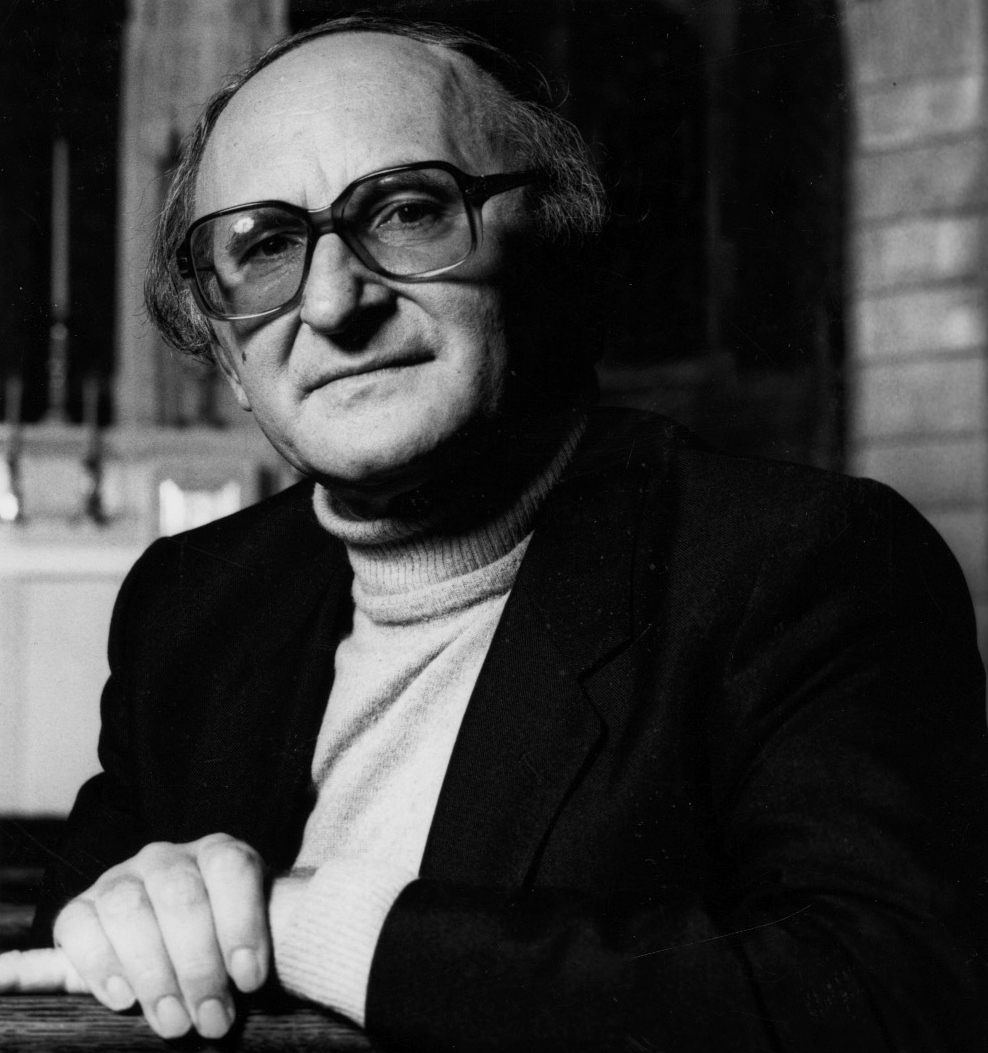

Fr. Johann Baptist Metz (Courtesy of Boston College)

Editor's note: "Take and Read" is a weekly blog that features a different contributor's reflections on a specific book that changed their lives. Good books, as blog co-editors Congregation of St. Agnes Sr. Dianne Bergant and Michael Daley say, "can inspire, affirm, challenge, change, even disturb."

Faith in History and Society: Toward a Fundamental Practical Theology

by Johann Baptist Metz

Seabury Press, 1980

In fall 1991, as a two-time alumnus of American Jesuit higher education (bachelor’s degree in religious studies, College of the Holy Cross; Master of Divinity, Jesuit School of Theology), I entered doctoral studies at Emory University imbued with the foundational theology of Karl Rahner. Emory’s formidable theological studies faculty had looked favorably on my stated purpose of pursuing liturgical theology, interested in better understanding the church’s sacramental practices as graced experiences in human ritualizing, a deeper grasp of symbolism as the divine means of human transformation.

Describing sacrament in terms of grace and experience rings of the German Jesuit Rahner’s fundamental method -- an effort at articulating everyday life as the locus of God’s presence to humanity, of God’s ongoing revelation through Christ in history.

The appeal of Rahner’s theology both to the American Jesuits who’d taught me and to myself, who by then had completed a decade of Jesuit formation, was due in no small part to a common spirituality, a renewed appropriation of Ignatius Loyola’s practices for discerning God’s active presence in the story of one’s life with others. Jesuits are formed for “finding God in all things,” a motto drawn from Ignatius' rules that more than two generations of U.S. Jesuit leadership had been promoting among our members and as a guiding principle for our colleges and universities.

Another motto had likewise emerged from the reforming mid-1970s General Congregation of the Society of Jesus: “The service of faith and promotion of justice” realized vigorous adoption as the new mission-mandate for the U.S. Jesuit provinces.

Rahnerian theology, focused as it was on the individual believer (the “subject,” in modern philosophical terms), provided limited scholarly support for applying the biblical and doctrinal content of Christianity to persistent and newly erupting social struggles -- whether public or ecclesial, local, national or global. At the extreme, “faith and justice” Jesuits and colleagues derided what they considered widespread self-absorbed spirituality among American Catholics, often targeting liturgical practices.

On that point, I was sympathetic, for I was disheartened by the extent to which I largely found Catholic celebration of Mass adapting its symbolic elements, seasonal cycles and biblical content either to the popular customs comforting their middle-class lifestyles or, conversely, to the social causes agitating them. Experience and study to date had convinced me that the rites, by then completely reformed in the wake of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), should form us, not the other way around.

Likeminded Catholics, however, were to my knowledge seemingly few, making me suspicious that something was amiss in Catholic and wider Christian culture.

My first semester of doctoral coursework at Emory quickly confirmed my decision to study with faculty and students broader than my Catholic circle.

Two of my seminars entailed extensive reading of the formidable Karl Barth. Theological ethicist James Gustafson had us studying huge portions of Barth’s 14-volume Church Dogmatics, but it was philosophical theologian Walter Lowe’s advice that for his course I concentrate on Barth’s early breakthrough book, The Letter to the Romans, that had an explosive impact on my thought.

Such an effect was, in fact, Barth’s very intention in writing some seven decades earlier. His was a clarion call to the churches in the wake of the human devastation wrought across Christian Europe in World War I, against which liberal, transcendental-idealist Protestant theology had proven impotent. In Romans, Barth elicits images from that catastrophe to interpret Paul’s message, likening the Gospel, most bracingly, to a bombed-out crater.

Into that void on earth’s broken surface, God’s Word comes as alien to humanity, an empowering, because completely other, message for living toward a new creation, out of hope that in this age remains ever on the distant horizon.

Barth’s resolute emphasis on otherness and distance from human capacities and inclinations he pressed as a damning corrective to experience-expressing theologies, the very type of method North Atlantic Catholic theology had largely come to embrace several decades later.

Still somewhat youthful, I found myself carried away with enthusiasm for the Barthian critique of modern Christianity’s institutionalism and social conformity. And yet, in passionate conversations with generous classmates, I could not help but realize that the Swiss Protestant theologian’s aversion to any sacramental efficacy through the church’s symbolic ritual in its members, along with his meager offers for positively explaining how the Gospel reaches humans as humans, severely limited his resourcefulness to my project.

In a further course with Lowe in my second year of studies, he again proved a solicitous guide for shaping a theological project in service to the malaise that I (with many others) perceived in U.S. Catholicism. The common work of the seminar was our poring over writings by early critical theorists, especially the “Frankfurt School” (Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse), while the professor individually assigned each of us a theologian in our particular traditions engaging such philosophy in their own work.

To me, he assigned Johann Baptist Metz, a German Catholic priest-theologian whose methodology and argument had most comprehensively come together in his Faith in History and Society. Metz’s critique of late-modern Catholic theology and practice, as well as his constructive proposals reorienting fundamental theology, spoke compellingly to my observations, questions and concerns.

Metz develops his practical fundamental theology on the thesis “that the widely discussed crisis of identity in Christianity is not primarily a crisis of the Christian message, but rather a crisis of its subjects and institutions. These are too remote from the undeniably practical implications of the message and so tend to destroy its power.”

Against the mistaken popular explanations of Christianity’s slide into increasing social and personal irrelevance -- namely, that the Bible and traditional doctrine are incapable of addressing the needs and interests of modern humanity -- Metz counters that such institutions as the theological academy and internal church structures have failed in their reactions to secularity. Thereupon, Metz constructs what he calls a “theological enlightenment of the Enlightenment,” a reexamination of Enlightenment history arguing for how the rise of the privatized individual has precipitated crises for religious tradition and authority.

Such analysis of religion’s reduction to a private middle-class affair opens into a fundamental theology addressing the practical conditions and possibilities for emancipating people (“the human subject”) by means not of abstract principles but of the practical categories of memory, narrative and solidarity.

Metz develops his “political theology of the subject” as a corrective to the transcendental fundamental theology of his mentor and friend, Rahner, whose theological anthropology he extols as the finest exercise exploring the formal subject produced by the Enlightenment. In reflecting upon existence, person, subject or the human, Rahner achieved the pinnacle of Roman Catholic theology’s belated response to Kantian transcendental philosophy.

The problem, however, is the level of abstraction. Modern theology has failed to ask whether such a religious subject actually exists, that is, whether or to what extent actual people in modern society approach their personal and societal lives on the basis and priority of Christian concepts of reason, freedom and autonomy.

As a privatized affair, Christian religion functions as affirmation of values the middle-class subject attains elsewhere in society. In the public sphere, it is reduced to providing customs for holiday celebrations. For a growing majority, Christian faith becomes a “religious paraphrase” of how they already perceive and practice their lives in the world, thereby making participation in liturgical worship expendable. Meanwhile, a much smaller minority, in contrast, seeks refuge in a rigid “pure traditionalism” that threatens the church with sectarian isolation.

In establishing the concept of political theology, Metz analyzes the threatening socioeconomic conditions of late modernity in order to argue that the Christian message can realize its salvific import today only if recognized as a “dangerous memory,” the memoria passionis.

Relying extensively on the Frankfurt School critical theorists, Metz describes the threat that the instrumental, “evolutionary” reason of technology and the market poses to humanity and ecology at this juncture in history. To the extent people accept the rationality of capitalism’s exchange principle and technology’s instrumentalism, the logic of inevitable (evolving) progress amounts to “a new form of metaphysics” or “a quasi-religious symbol of scientific knowledge,” often with negative social consequences.

Far from generating the sort of optimistic view of history and nature that characterized the 19th century, the present valorization of technical reason has produced deep measures of fatalism and apathy. People find themselves part of an anonymous, inevitable, timeless technological and economic process. The need to conform for success in these systems depletes people’s imaginations, inhibits dreams for the future, and ultimately threatens the loss of their subjectivity and freedom.

In its now near universality, the exchange mentality inherent to market capitalism integrally influences not only politics but also the foundations of spiritual life in a culture of the makeable, replaceable and consumable, eroding commitments, attitudes of gratuity, and capacities to sit with sorrow or feel profound joy. The strains on personal and social relations overlap. Frustrations, especially economic hardships, in the face of the inadmissible limits of the instrumental reason of technology, the market and political bureaucracies, can foment hateful fanaticism, for which Auschwitz stands as the haunting witness.

With that powerful symbol of modernity’s disastrous turn, Metz articulates the current danger to humanity, as well as the emerging social and political movements confronting the suffering that technological and economic processes have caused. Anonymous progress is interrupted by questioning whose progress, at what cost to the freedom of others and, with increasing awareness, to the ecology. Remembrance of the victims of these social processes constitutes an interruption of the abstract arguments for progress.

Metz then turns to the memory of Jesus, the narrative of whose passion, death and resurrection reveals God’s identification with and promise of redemption for all victims of humanity’s inhumanity.

The pattern of Jesus’ life and death, one of service to the oppressed, constitutes the pattern of life that can be salvific for Christians now, a pattern that promises an authentic subjectivity and freedom. Metz thereby recovers the tradition of the imitatio Christi -- an imitation dangerous both in the conversion it requires of its practitioners, away from a privatized view of salvation, and in the threat it poses to the conventional (evolutionary) wisdom of society.

This praxis of mysticism and politics, liturgy and ethics, likewise becomes the means for believers to know, in an experiential or practical way, deep joy and hopeful consolation, freedom lived in the presence of God, the God of Israel and Jesus, the God of the living and the dead.

Such is a brief rehearsal of Metz’s fundamental theological project. In his comprehensive book, as well as subsequent essays, he cites the Eucharist as the mystical source of the “remembrance-structure” for a social ethics true to biblical faith and tradition. With the details of the history, theology, and practice of liturgical tradition having remained beyond his purview, Metz has placed me in his debt, orienting the work of my doctoral dissertation and now two decades of sacramental-liturgical scholarship as an ongoing dialogue between political and liturgical theology.

[Jesuit Fr. Bruce T. Morrill is the Edward A. Malloy Professor of Catholic Studies at Vanderbilt Divinity School.]