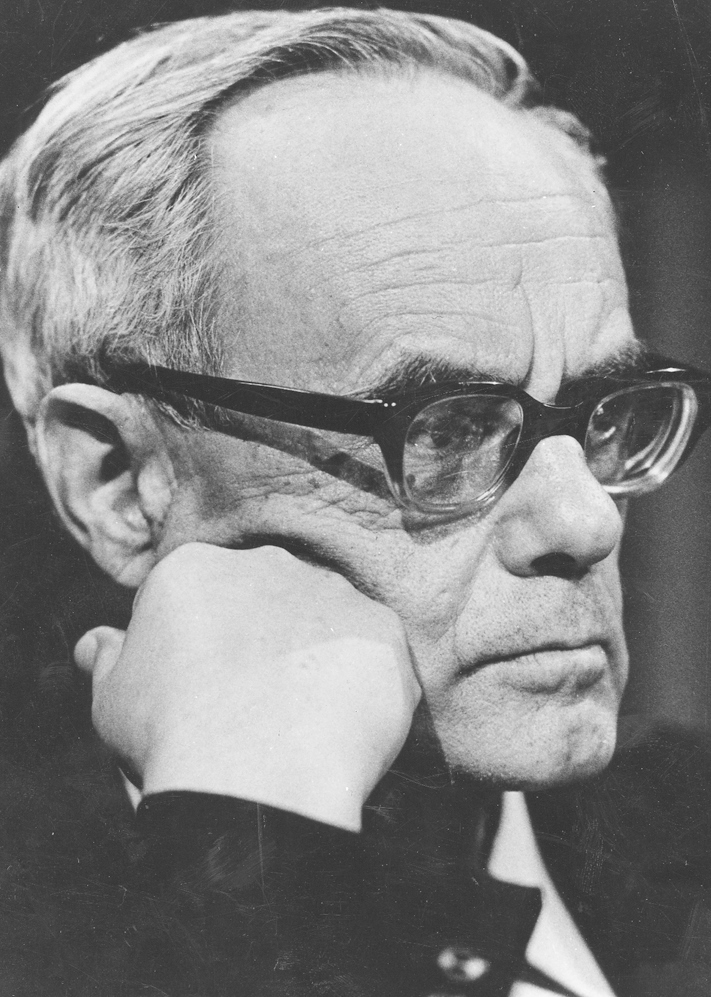

Jesuit Fr. Karl Rahner (NCR file photo)

Editor's note: "Take and Read" is a weekly blog that features a different contributor's reflections on a specific book that changed their lives. Good books, as blog co-editors Congregation of St. Agnes Sr. Dianne Bergant and Michael Daley say, "can inspire, affirm, challenge, change, even disturb."

Hearers of the Word

by Karl Rahner

(Herder & Herder, 1969)

The first edition of Jesuit Fr. Karl Rahner’s Hörer des Wortes appeared in 1941. It was the compilation of 15 lectures that Rahner (1904-84) delivered at the Salzburg Summer School in 1937 concerning the "Foundations of a Philosophy of Religion." The 1941 text was revised, with Rahner’s approval, by Johannes Baptist Metz; the revision was published in German in 1963 and in English, as Hearers of the Word, in 1969. As Metz observed in his preface to the revised edition, the book’s original publication during the early years of World War II was a major reason that its contribution to the philosophy of religion did not receive the attention it deserved until decades later.

I encountered Rahner and this work in the year before my graduation from college, four years after its publication in English.

Hearers of the Word is a work of fundamental-theological anthropology. In it, Rahner presents the human person as the possible hearer of the possible, free revelation of God in history. As with his previous major philosophical work, Geist in Welt (Spirit in the World), Rahner’s approach to his subject matter was influenced both by Thomistic metaphysics and Heideggerian phenomenological ontology. Spirit in the World and Hearers of the Word together provide the philosophical underpinnings of Rahner’s theological thought.

One of the fundamental ideas that Rahner develops in Hearers of the Word is potentia oboedientalis, the idea that human beings are oriented by their very nature toward the self-communication of God. Rahner made this assertion, and attempted to demonstrate its cogency, in a social and intellectual context that questioned the reality of God and the meaning of existence.

Although serious questions about belief in a theistic God had been raised since the Age of Reason, by the mid-20th century doubt and skepticism had descended from the ether of educational elites and had begun to permeate broader segments of the general population. The horrific human toll of the Second World War contributed to a growing sense of the absence of God. The question about life's meaning became more urgent.

In Le Mythe de Sisyphe (1942), published one year after Rahner’s Hörer des Wortes, Albert Camus described the absurdity of our continually asking the question about the meaning of life when, as he claimed, there is none. The absurdity of this paradox is embodied in the image of Sisyphus, who repeatedly pushes a rock up the mountain, only to see it roll back down, requiring him to begin the process of pushing it uphill again and again.

By contrast with Camus, Rahner argued that this unquenchable questioning was not absurd, but rather a constitutive feature of human nature, drawing us toward that holy mystery named God.

But for many people in the 1960s, God -- at least the God as traditionally conceived -- needed to be rejected so that human freedom and life could flourish. Three years before the publication of the English translation of Hörer des Wortes, an April 1966 cover of Time magazine asked, in large red letters over a black background, "Is God Dead?"

Thomas J.J. Altizer, a leading figure in the death-of-God theological movement, had affirmed in a 1964 essay, reprinted in book form in 1966, "God has died in our time, in our history, in our existence. The man who chooses to live in our destiny can neither know the reality of God’s presence nor understand the world as his creation; or, at least, he can no longer respond -- either interiorly or cognitively -- to the classical Christian images of the Creator and the creation."

Drawing on Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger, Altizer explained: "A No-saying to God (the transcendence of Sein) makes possible a Yes-saying to human existence (Dasein, total existence in the here and now)."

In Hearers of the Word, Rahner affirms not only the reality of transcendence, but also the reality of God, who nonetheless always exceeds being fully grasped by humanity.

"God is not a datum which can be directly grasped in his true self by man and his experience," Rahner wrote. God "is revealed every time man enquires into anything which exists, but who remains knowable only as the remote cause of that which is."

While atheistic thinkers asserted the absurdity and meaninglessness of existence, Rahner appealed to human experience, in which he claimed to discover the “openness of being and man” and transcendence toward God. Unlike those who concluded that God must die for human freedom to be (fully) actualized, Rahner showed how our fundamental openness to Being -- to God -- grounded and enabled our freedom, not curtailed it.

Drawing upon Heidegger’s notion that the question of the meaning of one’s being is preceded by a "pregrasp" (Vorgriff) of the world’s horizon of meaning, Rahner wrote: "Of necessity ... the question about being is part of human existence, because it is a concomitant of every proposition that man thinks or utters. He would not be human if he did not so think and speak. Every statement is a statement about some specific existent thing and is made against the background of a previous although implicit knowledge of being in general."

As Rahner develops this thought, he comes to the conclusion that the human person is "absolute receptivity for being pure and simple." Rahner called this basic constitution of the human person spirituality. He continues:

Man is spirit, that is, he lives his life in a perpetual reaching out towards the Absolute, in openness to God. This openness to God is not a contingency which can emerge here or there at will in man, but is the condition for the possibility of that which man is and has to be, even in the most forlorn and mundane life. The only thing which makes him a man is that he is forever on the road to God whether he is clearly aware of the fact or not, whether he wants to be or not, for he is always the infinite openness to the finite for God.

Encountering Rahner as a young adult, the appeal of his work was multiple. First, there was his method. Instead of arguing for the truth of Christian beliefs about the reality of God and human nature on the basis of Scripture or magisterial teaching, Rahner sought to establish their truth by directing attention to human experience.

His method asked me to turn inward and to reflect upon the process of acquiring knowledge, to ponder why we humans are creatures who ask questions and who, despite any answers we might get, always have more questions -- questions in search of an answer that might quench this seemingly unquenchable thirst.

Rahner’s method opened up for me the possibility of grasping the intelligibility of Christian convictions on the basis of experiences that I could correlate to the teachings of the church, rather than simply accepting those teachings solely upon the authority of another.

A second reason is related to the first. Rahner gave a strong example of how one could be a believing Catholic Christian while also having a questioning intellect.

The acceptability of asking critical questions -- even experiencing occasional doubt -- was a most welcome message to me in my young adulthood. But Rahner’s example carried and supported me beyond my younger years. As I pursued graduate studies and then a professional theological career spanning more than three decades, I frequently found myself returning to Rahner for inspiration.

Insofar as the human person is constituted by transcendence and freedom and insofar as God is holy (and wholly) mystery, Rahner encouraged theologians to exercise their freedom to explore this mystery creatively. He inspired me and many others not to be afraid of interpreting and applying the Christian tradition in new ways in the different contexts of our world.

As he made clear in Free Speech in the Church (1959), Rahner extended this right to voice one’s responsible views to the entire people of God, even if those views did not always elicit official ecclesiastical approval.

Although Rahner’s theological work played a major role in my decision about a future career, his was not the only influence. The Second Vatican Council, at which Rahner was a theological expert (peritus), was the other defining factor. The council’s pastoral orientation; St. John XXIII’s message of the "medicine of mercy" in place of words of condemnation; the council’s open, dialogical stance with regard to the modern world; and its desire to build bridges of understanding with other Christians and other religions -- all of this supported my decision, after attending Catholic elementary school and a Jesuit high school and college, to continue my education in a non-Catholic institution.

When I began my graduate studies in the Divinity School of the University of Chicago in 1975, the Rahnerian and conciliar spirit of dialogue and openness was palpable. The faculty included theologians and scholars of religion from different Christian churches and other religious traditions.

The Catholics among the faculty included David Tracy, Anne Carr and Bernard McGinn, and Catholic students constituted the majority of the student body in what had begun as a Baptist seminary. The Divinity School offered the stimulating environment in which the creative questioning that Rahner encouraged could flourish.

Hearers of the Word is not an easy book. It is filled with concepts and terminology drawn from transcendental Thomism, ontology, and modern phenomenology. Although Foundations of Christian Faith: An Introduction to the Idea of Christianity (Seabury, 1978) subsequently provided a more accessible introduction to the philosophical underpinnings of Rahner’s theology, it was my encounter with those ideas in Hearers of the Word that gave definitive shape to the trajectory of my professional life and offered me deep existential meaning.

[William Madges is a professor of historical theological at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia.]