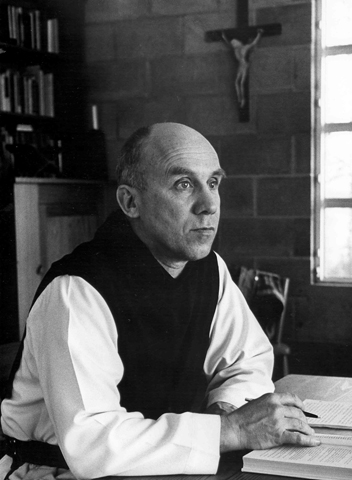

Trappist Father Thomas Merton, pictured in an undated photo. (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Editor's note: "Take and Read" is a weekly blog that features a different contributor's reflections on a specific book that changed their lives. Good books, as blog co-editors Congregation of St. Agnes Sr. Dianne Bergant and Michael Daley say, "can inspire, affirm, challenge, change, even disturb."

The Seven Storey Mountain

Thomas Merton

(Harcourt, 1948)

I was 17 and knew two things for certain. In fact, these two certitudes were crystal clear to me as a first-grader at Holy Name Elementary School. I wanted to be a priest and I was in love with JoAnn Mahoney. While there was never a serious doubt about seminary studies, I nevertheless felt the ripples of tension and unease rooted in mandatory celibacy. JoAnn Mahoney and celibacy! Still, in the spring of my senior year of high school I sat at my parents' dining room table and wrote the rector of Cleveland's Saint Mary Seminary seeking admission.

Now you should understand that my desire to be a priest was a pontifical secret. None of my classmates, not one, knew of my intention. The reason for the secrecy remains somewhat of a mystery to me to this day. I suspect my fear was that my high school friends would think me pious. And I definitely did not want anyone, especially JoAnn, to think of me as pious.

But one of my teachers, a Sister of Charity with the eye of a Fr. Brown detective, was on to me. Sublimely discreet, she said one day after class when my senior friends were out of earshot, "You might like this book." She handed me, as if it were D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover, a first-edition copy of Thomas Merton's The Seven Storey Mountain. I thanked her politely enough and stuck the book behind my fourth year Latin grammar text, fearing someone noticed her offering and might ask me about it.

Months later, I plunged into The Seven Storey Mountain with a first-year-seminarian's thirst for spiritual adventure and with the idealism typical of a religious novice. Merton's repudiation of his dissolute living, especially his early sexual indulgence at Cambridge and later at Columbia, was comforting. See, I told myself, women and beer and smoky jazz clubs left Tom Merton with a stale taste in his mouth, an emptiness in his soul, and rumblings of regret in his gut. He was, he wrote, "sick of being sick." By the mysterious workings of grace, Merton began to understand it was union with God and the saints that really mattered. To his surprise, he wanted nothing less than holiness. And I wanted what Merton wanted. His spiritual autobiography was the perfect book for me at the perfect time.

At the same time I was reading The Seven Storey Mountain, I was corresponding with a young nun in Baltimore, Md., whom I had met just before she entered the Carmelite monastery there. Teresa of Avila had encouraged her sisters to befriend a seminarian or priest and to pray for him daily. Sr. Colette of the Trinity became my prayer friend and soul mate.

Letters from Sr. Colette and reading The Seven Storey Mountain confirmed my budding passion for contemplative spirituality. I would be a diocesan priest, but a diocesan priest with a monastic, contemplative spirituality. So, the monk and the nun, more than the seminary's formation program, shaped my interior life. Still, the three of us, Trappist monk, Carmelite nun, and I, were all touched to some degree by the spiritual elitism that Merton came to regret after The Seven Storey Mountain shocked the publishing world with its unprecedented commercial and critical success. Only later did we see our Church's triumphalism, the smugness that Flannery O'Connor called "the great Catholic sin." Merton's own critique of his autobiography went further. He recognized and regretted his excessive moralizing and dualistic thinking that shaped his early understanding of holiness. Along with Merton, Sr. Colette and I moved beyond our early naiveté as we recognized the possibility of contemplative living for all of God's pilgrim people.

I missed all this in my first reading of The Seven Storey Mountain. The book was a light unto my feet. Like a pin to a magnet, I was drawn to the author's personal, engaging, heroic writing that fired my first fervor (so be the mixed metaphors). I agreed with the Chicago Sun reviewer James O. Supple, who wrote that the book was "a hymn of positive faith sung in the midst of a purposeless world searching for purpose, a book that can be read by men [sic] of any faith or none at all." But, as a seminarian, I had plenty of purpose in my own life -- the priesthood and the ministry that I would exercise as a "doctor of souls." So, let me tell you why Thomas Merton's The Seven Storey Mountain has so profoundly left its mark on my spiritual journey.

Merton's spiritual autobiography is a vivid, compelling adventure story of a lost soul searching for healing and wholeness -- for salvation. In telling his story, Merton becomes a kind of a modern Odysseus*. And so Merton emerged as a hero to me in my early years as a seminarian. In writing of his bouts with spiritual confusion and conflicting desires, Merton was writing about my own confusion and discordant desires. In struggling to surrender his willfulness to a willingness that forced nothing, he helped me to temper my own Pelagian efforts to grow spiritually.

It's pretty clear now that The Seven Storey Mountain served as my "spiritual director" during my first years of seminary formation. Merton's vivid writing, his spiritual honesty, and his heavenly quest fired my soul far more than any of the preached retreats we seminarians endured. Reading Merton I came to understand what the spiritual masters meant when they spoke of "living in the presence of God." He gave me a glimpse of the quality of his own soul, a soul now being molded by the rhythm of monastic life and contemplation born of solitude and silence. His was to be a lyrical spirituality inspired by the Fathers of the Church, neo-Thomistic theology, and traditional monastic devotion. Later, it would become an earthy spirituality, truly prophetic and nourished by Kentucky's rolling hills and Gethesmani's forest trails, by clouds and rain and the changing seasons.

In the final section of The Seven Storey Mountain, Merton writes of being on retreat at Gethsemani just months before entering and being moved by the monks' final chant of the day, the Salve Regina. "… [T]hat long antiphon, the most stately and most beautiful and most stirring thing that was ever written, that was ever sung." Yes, I said to myself as I underlined these words in my text. I knew precisely what he meant. Diocesan seminarians traditionally end their day with the singing of the Salve Regina in their darkened chapel lit by a single candle next to a statue or icon of Mary. Here Merton was speaking for seminarians everywhere. I like to think that the most treasured seminary memory we priests hold is this chanting of the Salve.

Not too many years ago, Cleveland priests were gathered at our seminary to mark its 150th anniversary. Invited to the celebration were all the priest alums including those men who left the priesthood to marry. A few of those who had left active ministry came with their wives. The celebration ended with Vespers and the chanting of the Salve. From my position near the back of the chapel, I was moved when I saw that these married men, holding the hands of their wives, had tears running down their cheeks as the Salve awakened in them still sacred memories -- their wives surprised by the wave of emotion rising up in their husbands.

I seldom preach a retreat without quoting Thomas Merton. Not so much from The Seven Storey Mountain, as from the books that flowed from Merton's pen after the publication of his autobiography. Books like Seeds of Contemplation, The Sign of Jonas, No Man Is an Island, Thoughts in Solitude, New Seeds of Contemplation, and Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, along with Merton's poems, journals and collected letters. But it was The Seven Storey Mountain that first shaped my spirituality and led me to these later works that define Merton as a spiritual master**. Here are two of my favorite Merton maxims: "A retreat is a time to do nothing for as long as you can." And "In humility is perfect freedom." This latter quote is Merton at his laconic best. Here we have a true seed of liberation. When we put our ego-self aside, something rather strange occurs -- we don't care too much what others think of us. We're free to be who we are meant to be -- our true self. Surely a key foundation stone of spiritual freedom.

From time to time, I've been asked if I ever considered joining a religious order. The thought of being a Dominican or a Jesuit priest never crossed my mind. No, my vocation was to the diocesan priesthood. But the thought of being a Trappist priest, a contemplative priest, that idea did break into my consciousness, but rarely. And those occasional imaginings were due to The Seven Storey Mountain. No, my truth was the diocesan priesthood. But as my seminary years passed by and ordination drew near, I came to see more and more clearly that my ministry as a priest needed to be grounded in a contemplative spirituality.

Moreover, Merton and others, but especially Merton, have convinced me that the path to ecumenical and inter-religious communion -- and to peace and justice -- is found in the contemplative centers of our world and in the hearts of those of us trying to lead contemplative lives. Thomas Merton, I believe, like the great Karl Rahner, understood that the Christian of the twenty-first century will be a contemplative or not at all.

[At present Fr. Donald Cozzens is writer-in-residence and professor of theology at John Carroll University. He was the long-time president-rector of Saint Mary Seminary and Graduate School of Theology in Cleveland, Ohio. He is the award winning author of The Changing Face of the Priesthood.]

[Author's footnotes below]

*Anthony T. Padovano, The Spiritual Genius of Thomas Merton, Franciscan Media, 2014, 47.

**See the Introduction in Lawrence Cunningham’s Thomas Merton: Spiritual Master, Paulist Press, 1992.