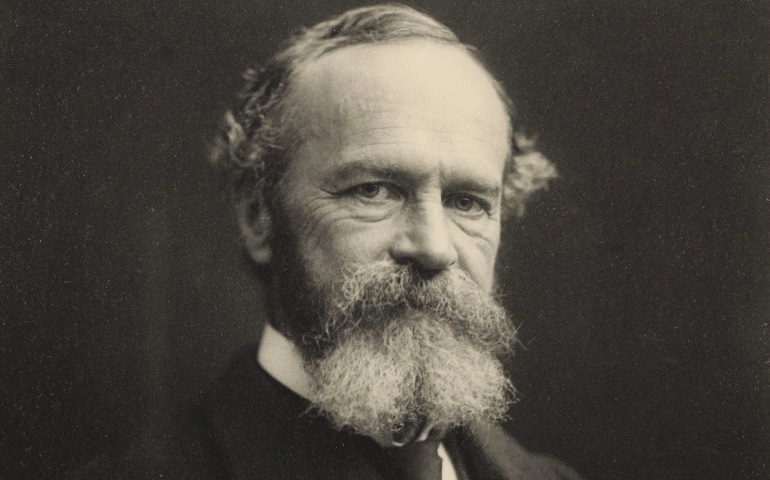

William James in 1903 (MS Am 1092, Houghton Library, Harvard University)

Editor's note: "Take and Read" is a weekly blog that features a different contributor's reflections on a specific book that changed their lives. Good books, as blog co-editors Congregation of St. Agnes Sr. Dianne Bergant and Michael Daley say, "can inspire, affirm, challenge, change, even disturb."

The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature

by William James

Longmans, Green, and Co., 1902

Whenever I take up and reread The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature by William James, my spirits soar. My mind takes off and my faith becomes more deeply grounded. No wonder that after a hundred and some years these 20 Gifford Lectures published in 1902 are required reading for anyone interested in the psychology of religion.

Here, the brilliance of William James dazzles and delights readers with displays of originality built on wide knowledge. And why not? His wealthy and eccentric father, Henry James Sr., had supported William's prolonged studies, here, abroad and back again. Along the way, James mastered languages, philosophy, literature, science, medicine, psychology and the art of drawing.

Only after much intellectual and psychological turmoil was James at last able to settle into an academic berth at Harvard, teaching philosophy and psychology. During the turbulent years, William struggled to gain direction, overcome health problems and fight through serious suicidal depressions. His passionate temperament, amazing energy and formidable will finally triumphed. Over the decades, he taught his academic classes, lectured widely, and produced a huge amount of writing for both academic and general audiences.

James always speaks directly to the reader. He invites you to join him in whatever urgent inquiry he is pursuing. In Varieties, he takes on the most basic religious questions that individuals face in their lives. Why and how does a person come to believe -- or doubt? And why does it matter to the universe? James' focus is always on the individual subject as primary; he is not interested in the external study of religious institutions or abstract theological doctrines.

As an empirical, scientific psychologist, James seeks to understand the inner story -- the subjective, emotional and intuitive dimensions of personality. Feelings count most in determining faith and behavior.

You may not always agree with James, but you cannot help being impressed by the energy and acuteness of his arguments. It helps that William has mastered an informal streamlined prose (quite different from that of his brother, Henry James Jr., the literary star). Yet his dramatic firsthand accounts of individual conversion or despairing depression are gripping reading. James punctuates these narratives with nuanced analysis and ironic sparks of wit.

My own debts of gratitude for this book by James start with his initial arguments dealing with "the neurology question." Skeptics and materialists in his day, as in ours, confidently took the line that religious beliefs merely manifested the superstitions of a brain's disorder. But James argues that religious experiences cannot be dismissed as neurotic brain products. Why? Because in the natural scientific order, every human mental thought, skeptical materialist or religious belief, originates in the brain. We fail to notice this because only the ideas we already disagree with are deemed neurotic.

In science and philosophy, we must rationally judge the value and worth of beliefs and feelings by other criteria and standards. On the whole, we ask, do religious ideas and experiences meet three criteria:

- Are they morally helpful?

- Do they make cognitive sense with everything else that is known?

- Are they immediately luminous, i.e., generating feelings of light, trueness, goodness, joy and love?

In other words, good or bad, general effects should be the standards of evaluation; by their fruits shall you know them.

James then proceeds in the rest of the lectures to give multitudes of examples demonstrating the mainly positive effects of religious experiences. He writes chapters on the reality of the unseen, conversion, saintliness, mysticism, philosophy and happiness. These treatments remain classics, along with his discussions of individual differences in religious temperaments, such as the healthy-minded and sick souls.

These arguments in defense of religion by James were liberating for me as a convert to Roman Catholicism. My religious mother had been afflicted by schizophrenia and in my aggressively secular family there lurked the suspicion that my ardent religious enthusiasms were signs of pathological tendencies. Yet my faith could meet James' threefold criteria of validity. I was morally helped, intellectually strengthened and joyfully blessed -- for all the long productive life to come.

James served as a sophisticated defender of the faith in atheistic academic milieus encountered. There, too, religious fervor and commitments also carried the odor of craziness. Indeed, James was quite ready to propose that a more sensitive and even neurotic temperament might be more receptive to valid religious truths than more a stolid, unimaginative nature.

Here, James himself was a case in point, although he never claimed any truly mystic experiences and remained outside of any committed Christian denomination. He was always an in-between thinker, too religious for the secular materialists and not avowedly religious enough for the orthodox.

For many, the scientific empirical investigatory approach James employs is quite convincing and effective in defending religion's value. He gathers religious testimonies from history and across cultures. In Varieties, James gives many, many accounts of enthusiastic, ecstatic religious experiences as well as descriptions of the tortures of despair over the meaninglessness of human life. Counter conversions and indifference also make appearances.

Believers can be grateful for the preponderance of so many testimonies of the joy and ecstatic happiness provided by the wonder of God's love. (Irish Catholics can be quite reticent on such matters!) Despairing doubt is more generally acceptable in postmodern times. Yet a whole range of voices appears in Varieties.

Readers hear from Christian saints, mystics, literary geniuses, mediums and mind cure practitioners, scientists, missionaries, ancient sages, Eastern mystics, and ordinary people of all classes. More than a hundred accounts are presented. Augustine, John of the Cross, Teresa of Avila and George Fox rub shoulders with Tolstoy, Emerson, Walt Whitman and less familiar scientific authorities of James' era. In the end, this cloud of witnesses brought forth to testify to the positive fruits of religious belief gives support to one's own faith.

James was interested in everything to do with religion. He honed in on how individual temperament interacted with belief and religious experience, or lack of it. Some personalities were incapable of faith, he believed, because their deeper intuitive sources were "frozen," or blocked by the social circles of disbelief they inhabited.

Others were religiously "tone deaf." Still others could never reach a level of self-consciousness to question or doubt. But in conversion or counter conversions, inner fields of energy could shift, hot spots of burning interest could cool or vice versa. James did not think that science or psychology yet understood these dynamics of the inner life of human beings. He did not presume to say whether supernatural influences could be at work. Science was still in its infancy and the mysteries of a pluralistic universe should be acknowledged.

Certainly, James was prescient and well ahead of his time in giving serious weight to innate individual differences, to scientific evolution's processes, to the power of emotion, intuition, mind and fluctuating levels of consciousness. For him, reality is dynamic, flowing, integrated and full of probabilities.

All of these ideas make James sound fresh and up to date. Academic psychology has only belatedly returned to James' concerns with the power of the mind, the centrality of emotion, and the quicksilver stream of consciousness. Religious experience is now a respectable field in academic psychology.

So, in sum, I owe James for being a guide to my intellectual vocation. Trying to understand the relationship of religion and psychology is the life for me.

In Varieties, James is necessarily ecumenical because of his broad basic definition of religion. Religion is the realization that there exists in reality an invisible order and it is humanity's happiness to integrate themselves with it. The vast unknown realms in the pluralistic universe exist as more. Since things are not well with us humans, high religions of deliverance like Christianity and Buddhism can provide ways to holiness and happiness.

William James was criticized in his day (and ours) for his radical empiricism and pragmatic lack of interest in abstract philosophy, metaphysics and theology. Well, yes, true enough. And as a second generation Scots-Irish Protestant Yankee, he doesn't really get the communal, embodied, corporate spirituality of Roman Catholicism. But no one is perfect.

James was amazingly humble in his search for the more. The mystery of reality and religion never stops calling forth his passionate efforts to understand. I am not the first to join his unique and exhilarating campaign through the fields of religion and human nature. But others may not have had him confirm their sanity, appreciate their ardent joys and endorse their intellectual and vocational path.

Yes, I am in love with William James, but even more I wish I could be William James.

[Sidney Callahan is an author,