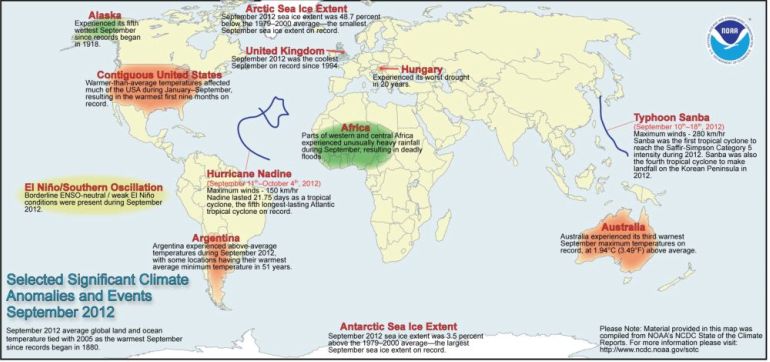

The month of September tied with 2005 as the warmest September on record, dating back to 1880. September 2012 also marks the 36th consecutive September and 331st consecutive month with a global temperature above the 20th century average, according to the National Climatic Data Center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA.gov)

With the presidential campaign trail narrowed to a mere six days before it enters the hands of voters, it would seem candidates Barack Obama and Mitt Romney would have exhausted most of the issues important to the electorate.

But that’s not the case.

As the activist group Climate Silence and others have pointed out, for the first time since the 1984 presidential election cycle, the debates of the 2012 presidential election were void of any mention, much less discussion, of climate change.

Recently, Obama broke his climate silence, but only slightly, and through a largely unnoticed interview with MTV.

"We're not moving as fast as we need to. And this is an issue that future generations, MTV viewers, are going to have to be dealing with even more than the older generations, so this is a critical issue," he told the cable network.

The president went on to differentiate his and Romney's stance on climate change's cause, saying "[Romney] says he’s not sure that man-made causes are the reason. I believe scientists who say that we’re putting too much carbon emissions into the atmosphere, and it’s heating the planet, and it’s going to have a severe effect."

Romney, for his part, has largely ignored climate change as well, save for a line from his Republican nomination acceptance speech regarding the president’s past promises: “President Obama promised to begin to slow the rise of the oceans," Romney said, "and to heal the planet. My promise is to help you and your family.”

The silence from both parties comes as more and more Americans acknowledge that the planet is getting warmer. A mid-October study by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press found that two-thirds of Americans (67 percent) believed that the earth’s average temperature has warmed over the past few decades – a 10 percent upward shift since 2009.

The same study found that more people are also seeing a correlation between the rising temperatures and human activity, as 42 percent believe we have had a role in the rise; 19 percent attributed warming to natural patterns, a dramatic drop from 2010 when 34 percent of those polled held that view.

While people identifying as Democrats are far more likely to acknowledge global warming (85 percent), almost half of Republicans (48 percent) do as well, as do 65 percent of independents.

But the numbers of people among all three groups acknowledging global warming are still lower than in previous years — in 2006, 91 percent of Democrats, 59 percent of Republicans and 79 percent of independents said the evidence pointed toward rising temps (77 percent of all those polled).

What, then, has led to the shift to silence on the campaign trail when it comes to climate change?

An Oct. 23 PBS Frontline report – "Climate of Doubt" – examined this exact question.

The report highlighted the efforts of a variety of grassroots and activist groups – Americans for Prosperity, the Heartland Institute, the American Tradition Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Cooler Heads Coalition – who sought to weaken the growing consensus about climate change after Obama's election by cultivating doubt in scientists and fear in climate-related policies.

By framing the climate change discussion in terms of government expansion, skeptics could find success in advancing their view, even with 97 percent of scientists seeing climate change as a reality, and politicians as diverse as Nancy Pelosi and Newt Gingrich saying together that it is a serious problem, the report found.

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the Frontline special was the story of Bob Inglis, an incumbent, six-term South Carolina congressman who lost in a 2010 Republican primary by a staggering 79-21 count. Despite his largely conservative record, Inglis attributed his loss to his acceptance of the scientific consensus on global warming.

“And there’s nothing like a loss in an election to promote fear in the survivors,” Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry told Frontline.

Others have opined that climate change is still viewed as a side issue important only to a minority of people, or that the likely costs of addressing climate change would snowball a candidate’s campaign, as in the case of Inglis.

[Update: The U.K.'s Guardian reported a story Nov. 1 about a pivotal March 2009 meeting that provides insight into the Obama administration's framing of the climate issue.]

While discussions of climate change on Capitol Hill appear to be on mute, more and more leading news outlets have come to recognize its omission.

A recent story on the cover of the New York Times reported on the lack of climate conversation, saying "Many scientists and policy experts say the lack of a serious discussion of climate change in the presidential contest represents a lost opportunity to engage the public and to signal to the rest of the world American intentions for dealing with what is, by definition, a global problem that requires global cooperation."

And in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, The USA Today editorial board took up climate change politics. While not suggesting climate change the cause of a single storm system — “no individual weather event can be conclusively linked to man-made climate change” — the editorial concluded that extreme-weather events are becoming more common, and that a real conversation about climate change, however uncomfortable it might be, must come soon, lest “the costs of inaction, in tragedy and property, might be even greater.”

In his MTV interview, the president, after highlighting his work to increase automotive fuel efficiency standards and to double clean energy production, hinted at a partial plan on climate change, saying increasing energy efficiency in buildings is the next step to reducing carbon emissions.

But Obama acknowledged a true, global solution will require "technological breakthroughs," and greater partnership with countries such as China and India, whose economies continue to grow on the fumes of coal-fired power plants.

Whether he or Romney will actually bring volume to discussions of those breakthroughs in January remains to be heard.