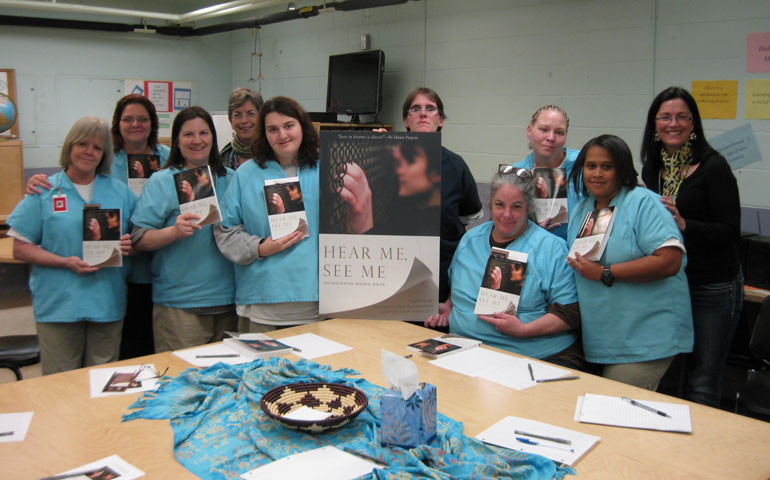

Marybeth Christie Redmond (far right) and Sarah Bartlett (fourth from left) with writers of Hear Me See Me: Incarcerated Women Speak at Chittenden Correctional Facility in Vermont (Courtesy of Marybeth Christie Redmond)

The last thing on earth I anticipated as a vocation was writing with addicted, mentally ill inmates inside a prison facility. These women, ages 20-65, at Chittenden Correctional Facility in northern Vermont have dealt drugs, driven drunk, abused children, embezzled employers, robbed convenience stores at gunpoint, and even murdered their own kin. They have also taught me to become a more vulnerable person, and about reservoirs of mercy and compassion I never knew I had.

I came to this work as a journalist covering marginalized communities for 25 years. More advocate than reporter, I always battled a desire to change systems rather than cover them objectively, a bit of a deal-breaker for a journalist.

But despite past encounters with jailed persons and correctional systems, I was unprepared for the profound soulful connections I would develop with Vermont's incarcerated women by writing weekly with them for four years. Nor could I anticipate the life lessons they would bequeath me.

Most prison volunteers don't want to know the gory details of inmate transgressions, but to be honest, I'm interested. I want to challenge myself to the depths of living an authentic Christ-centered life. Can I encounter what society sees as the most broken, vile ones -- the bottom of the human "food chain" -- and behold the face of Christ, feel the energy of Christ? Can I surmount the human recoil factor in myself and receive these voiceless ones as Jesus did?

I could certainly roam the hallways of Chittenden emanating Pollyanna-like mercy to counteract the chaos of clanging metal doors, officers barking commands, an environment void of color, and women in severe stress. Yet a greater challenge would be to enter this highly prescribed world open and receptive, as Jesus did in the life-changing encounters of his day. I am learning that transformation comes not from trying to change other people, but from the vulnerability needed to shift the way we see and experience them.

As a result, when co-founder Sarah Bartlett and I began the "writing inside VT" program (writinginsideVT.com) in 2010 within Vermont's singular women's prison, we made a decision to write as vulnerable participants. The purpose of the program is to use writing as a tool for self-change and to build healthy community. So we too put pen to page to see with a fresh eye our own struggles with depression, dysfunctional relationships, underemployment and varied experiences of marginalization. It seemed critical that a sacred space be created "inside" where mutual relationships could exist and Holy Spirit-level transformation could swoop in unannounced for each of us alike.

And that is precisely what has resulted. Our ever-changing circle of 15 to 18 weekly writers has congealed into a tight-knit community of women who learn, practice, grieve, hope, vision and celebrate together, where there is nothing to whitewash in past or present lives. More than 200 imprisoned women have participated in "writing inside VT."

On a given night through her prose, Stacy shows us what unbridled anger looks like when you've grown up in a household that fails to provide for your safety and security. We all learn to be less afraid of rage:

I'm bleeding, but no one cares. I am alone. A goldfish among sharks. A sheep in wolf's clothing. I try to blend in, but my heart gives me away. I am scared, confused, forced to be someone I'm not. Made to believe it was the only way.

Raven models for us a deep acceptance of self and the quirks that uniquely mark each one of us as part of the human condition:

They say, "crazy, nuts, cuckoo," yet they whisper, "shh, she's mentally ill."

They say, "off her rocker, in la-la land," yet they whisper, "shh, she's mentally ill."

I begin to whisper, "smart, confident, a good person and mom," yet I think, "I am mentally ill."

Why am I mentally ill? Why are we whispering?

I go to my safe place where I crouch and can hardly breathe.

I whisper, "I am not mentally ill, I am just merely me."

Through the poetry of Tess, we learn what authentic surrender to the divine sounds like when battling an insidious addiction (as we all do, in some form or another):

It is me your daughter.

I am here in your light,

broken before you.

Please show me what it is

you want from me.

I am at your mercy;

I am on bended knee,

asking for you to hold me,

comfort me, show me how

to control my fear of the world.

It is a favorite prayer I keep tucked within the nightstand to murmur to the good Lord in my own anxiety-wracked hours.

And then there's Norajean, who calls herself a "slightly cracked child of God." Incarcerated again, she pours herself into the writing each time. Her words help us understand how deep wounds can reach inside:

Those of us who survive here

by reading scars

finding faults

before they open up and

swallow us

talk gingerly.

We learned early

to whisper, tiptoe, skirt

our way around.

We, who live by losing

love and letting go,

endure random uprooting.

The writers' penetrating honesty provides a springboard from which to unpack my own past difficulties. As I give voice to unclaimed aspects of my life, I feel inner strength regenerating, and the "inside" women who hear my stories feel less alone:

Piles of psychic wreckage

sometimes border

on landfill scale.

I step along the surface,

picking and sorting

through the heap

of composting emotions.

When a person has been brought to her proverbial knees, there is nothing left to protect. I walk freely in a world beyond prison walls but have learned much from these incarcerated women's humble stance. Their lives challenge us all to co-exist vulnerably with each another, to free up guarded places, fulfill unrealized visions, and speak our own truths to power.

And just as these women recover self-worth by learning to see themselves and others with the eye of their souls, so too must society at large receive the voices of its most marginalized members in order to evolve. At first this humble stance fits us as uneasily as an orange jumpsuit or the like, but it will empower us "to put on the clothes of Jesus Christ" (Romans 13:14), and see and be with "the least of these my brothers and sisters" (Matthew 25:40) in the core of our beings.

[Marybeth Christie Redmond is co-editor, with Sarah W. Bartlett, of the new book Hear Me, See Me: Incarcerated Women Write, which she'd like NCR readers to know is the brainchild of Soul Seeing editor Mike Leach, who read these women's words for years at writinginsideVT.com and declared, "This is a book!"]