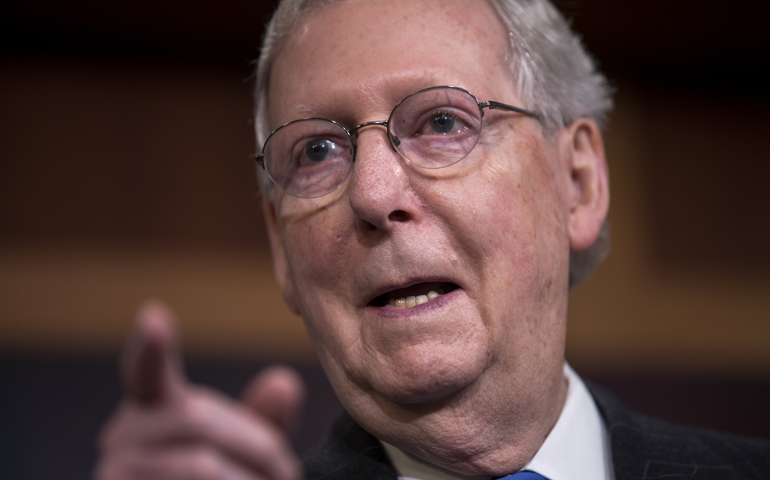

U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., speaks to the media April 7.

Don't be confused. This column is not about the Supreme Court. This column is about leadership of the democratic system. And its lack. In the Senate.

But first, a caveat:

I would be writing this column regardless of which political party was currently involved.

I see the rising number of attacks on bipartisanship as potentially — eventually — damaging to both national political parties. It erodes the spirit of the U.S. Constitution and the democratic character of the country itself. And all of this at a time when real nonpartisanship — real patriotism, not party politics — is most needed in a country whose nerves and trust have been strained to the ultimate.

What's more, I admit I'm biased: I'm a Benedictine and the very first word of Benedictinism's ancient Rule is "Listen." Thanks to American politics, I’m beginning to understand how momentous such an admonition really is. And more than that, it’s clear that we’re not doing it anymore.

Here's the history; here’s the problem.

The bicameral configuration of the U.S. Congress into House and Senate is a purposeful and important one. It was clearly constructed for just such a time as this when tensions are high and all the votes are close.

The House of Representatives with its 435 members is drawn from multiple small districts for two-year terms. It is, as a result, close to the people and their emerging concerns. The members of the House are the thermometers of a fast-changing society.

The House is meant to give power to the people, to raise immediate issues immediately and to give quick attention to serious but possibly quick-changing questions.

The Senate of the United States, on the other hand, is a smaller, more deliberative body. After all, the 100 senators with their six-year terms are going to be around long enough to suffer from the effects of superficial decisions made too quickly. The Senate, therefore, can afford to move more slowly than the House. Or as the founders themselves planned, senators, unlike the fast-changing representatives in the House, would have the time to inject deep thought, far vision and so, good sense, into the programs of government.

The Senate is about not being hasty, in other words. It’s about thinking again. It’s about not allowing a narrow majority to bulldoze a large minority into legislation that ignores the needs of half the country. It’s about bringing wisdom to politics.

Long, drawn out filibusters, for instance, enable a minority party to block an upcoming vote by holding the floor until the parties reach a compromise solution. Supermajorities require more than a one-point margin to pass a resolution. It is easy to think that the simple majority — a mere 51 votes out of 100 — is the mark of democracy but, in some cases — in cases of narrow majorities deciding major and polarizing issues — unity clearly requires broader margins than that.

Change of scene to now:

Sen. Mitch McConnell's Republican caucus with its four-seat advantage first refused to even take Barack Obama's Supreme Court nominee, Judge Merrick Garland, to the floor for consideration despite the fact that no law, no rule, required it.

Then, in the newly minted Trump administration, they passed the cloture vote that ended the democratic filibuster intended to obstruct the Senate from voting on Judge Neil Gorsuch’s appointment to the Supreme Court so that a candidate acceptable to both parties could be found.

Finally, they unleashed the "nuclear option": They changed the number of votes needed to approve that appointment from 60 to 51. And at that point, all pretense at genuine democracy ended in that august chamber.

So much for the sober and indomitable, the wise and thoughtful character of the Senate.

Watching the U.S. Senate — its Republican caucus specifically right now, under the highly partisan leadership of McConnell — tear up the traditional 60-vote standard for the approval of Supreme Court justices is enough to make politics obscene. It may well, in fact, be the debacle of this Congress. It is a petty, shortsighted, and potentially politically destructive act.

Yes, I know that then Majority Leader Harry Reid, in true kindergarten style, started this era’s game of political tit for tat; Reid used the same nuclear option to cut off Republican attempts to block federal judicial and executive branch nominees in the Obama administration. Like most parents I know, I am suggesting that we do not accept "They did it to us first" as a reason to keep on doing what was never reasonable in the first place.

As President Trump loves to say in regard to much less important issues and without the kind of obvious impact involved in this case, it’s "Sad. Sad." Just when both leaders of both parties should have refused to even consider a move as dangerous to the country's democratic integrity as this, just when both of them should have said to the country, "We could change the Senate's operating rules to avoid the hard work of consensus but we won't endanger the future like that," they failed us.

So much for the sober, steady leadership of the Senate.

Instead of a noble struggle for consensus, what we're getting is a prolonged schoolyard fight between swaggering adolescent boys still suffering from a lack of adult insight, and displaying even less emotional control. This so-called "nuclear option" is the first really dangerous snowball thrown at the democratic process by the very body intended to preserve it.

Worse, it begins an almost sure but surreptitious movement to end the filibuster entirely, the move to talk a bad idea to death. It threatens to reduce U.S. democracy to majority rule by cutting off both debate and discernment. While the opposition sits back silenced and silent, the ruling party will run the country.

In the face of such raw power-grabbing, 61 senators — 28 Republicans, 32 Democrats, 1 Independent — wrote a public letter to the leader of both parties, McConnell and Schumer, to preserve the use of the filibuster for legislative matters. Whether that position can possibly stand in the face of this apparently easy takeover of the Senate as a body, is highly questionable.

From where I stand, this problem is about process, not content. The problem we have right now is as much about how we decide what happens in this country as it is what we might eventually decide.

The truth is that we no longer have a real Congress that determines together what is good for the entire country. We have power politics, the abandonment of consensus, in a time of serious national division. The party with the most seats runs the country for its own satisfaction. How long that can possibly last is anybody’s guess.

Now, given the unwillingness to compromise, the House pushes through health care bills that endanger the entire citizenry and the Senate refuses to consider an independent prosecutor to take politics out of crucial constitutional questions.

The problem we’re facing is a leadership problem. This is about the preservation of a real two-party system. We have a simple question to answer: Are our leaders themselves committed to the democratic process?

The answer to that question will determine how we approach far more than judicial nominations. In fact, FBI Investigations, the national budget, health care legislation and a slide into militarism are all with us right now and the rightness of all of them — the future of this country — depend on it.

Indeed: "Listen!"

[Joan Chittister is a Benedictine sister of Erie, Pa.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Joan Chittister's column, From Where I Stand, is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.