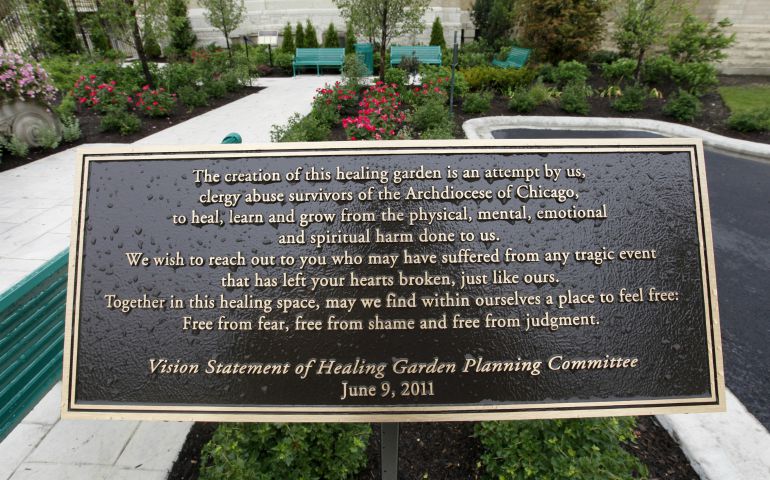

A sign stands at the entrance of a healing garden on the grounds of Holy Family Church in Chicago in this June 9, 2011, file photo. The garden was created as a place of prayer and healing for survivors of clerical sexual abuse, their families and the greater Catholic Church. (CNS photo/Karen Callaway, Catholic New World)

The parents of boys who accused a priest of sexual abuse wrote to the Chicago Archdiocese more than two decades ago: "Your repeatedly asking 'what do we want'? is one more insult. 'What we want' should be totally obvious. We want something done about these priest's." [sic]

Next week, June 15, marks the 25th anniversary of the Archdiocese of Chicago's announcement of the intent to create a review board to remove priests, such as the one mentioned by the parents. While publicly available files clearly document that church officials knew about the priest's behavior since at least the late 1980s, they did not report him to the authorities or remove him from ministry.

It was not until 2005 that the priest resigned from being a pastor and moved to a "monitored" setting. Two years afterwards, the priest had a young relative stay in his bedroom overnight while the priest's monitor was out of the country. After this incident occurred, the archdiocese began the process of laicization, or removing him from the priesthood.

Many abusive priests, like the one above, have voluntarily left or been removed from the priesthood, which begs the question, who is monitoring them now? The answer: nobody.

Over the last year, I have researched via publicly available documents the current or last known address of the 33 Chicago Archdiocese former priests accused of abuse, still alive today, who have left, resigned, or been laicized. I was able to locate the recent whereabouts of 29 of these individuals. Of these, five men reside, or have recently resided, within 500 feet of a school or daycare facility. Eleven of these abusive individuals have resided within 1,500 feet.

Of these 33 men, none of whom any longer are affiliated with the archdiocese, two are currently in state or federal mental health facilities, accordingly to publicly available documents. The rest live, unmonitored, in local communities.

For those who want to protect their children, there are three important facts to know.

First, out of the 33 men I researched, only one former priest is part of a sex offender registry. Church officials covered up crimes for so long that in many cases the statute of limitations for criminal charges expired. Many survivors were thwarted from suing in criminal court that would have led to their perpetrator being listed on an offender registry. As a result, many abusive priest names have never been on a registry, and cautious parents who check a registry for individuals in their neighborhood will not find former priests listed.

Second, former abusive priests can live near schools. Since former priests who abused children are not monitored by the state or diocese, there are no restrictions on where they may live.

In my home state of Illinois, offenders who are part of a registry are not permitted to live within 500 feet of a school or facility providing services to children under 18. Many states create similar boundaries between 500 to 2,000 feet.

My research found that at least 16 — approximately half — of the abusive former priests from the Chicago Archdiocese currently reside or have recently resided within close proximity of a school or child services facility, ranging from less than 500 feet to under 1,500 feet.

I recognize that the distance to a school may seem like an arbitrary boundary to safeguard children. However, it is a sobering reminder that if church officials had not shielded these men from the law or fought to keep the statute of limitations, some of these men would be registered sex offenders and, thus, identifiable to concerned parents and teachers.

Third, after legal and public pressure, some dioceses have taken the step to post the names of accused priests on their websites. While this is a step towards transparency, it is not as complete as a sex offender registry that would provide location information and current photos. Additionally, while registered sex offenders usually must re-register after having moved, former priests can move without notice. So a man whose name appears on a list of abusive priests in the Boston Archdiocese could move to Chicago and not appear on the Chicago Archdiocese list.

I contacted the Chicago Archdiocese for a comment and to inquire if they had taken any additional steps to safeguard children from former abusive priests. At deadline time, I received an email from Colleen Tunney-Ryan, the archdiocese's director of public relations and internal communication.

The email outlined steps the archdiocese has taken in its "long history of addressing issues related to the sexual abuse of minors whether by priests, employees or volunteers" and notes that the charter for child protection the U.S. bishops adopted in 2002 was largely based on the program the Chicago Archdiocese set up in 1992.

The email also noted, "Because allegations are often received decades after the incidents they describe, the civil authorities have, for the most part, not prosecuted cases in the criminal justice system." What it fails to mention is that Illinois Catholic Bishops fought to keep statute of limitations that prevents cases from moving ahead.

The email also noted that the archdiocese "has no authority over former priests."

While dioceses may not monitor former abusive priests, concerned Catholics and other citizens may take some steps to safeguard their children. You can learn the warning signs of abusive people and how to talk with your kids about safety. You may also check BishopAccountability.org. The organization is the only site to comprehensively catalog the Catholic abuse crisis. The website contains a database of publicly known sexual offenders from the church that you can search by diocese or name.

Most of all, Catholics can continue to advocate for holding bishops accountable for the sexual abuse crisis. This month marks the 15th anniversary of the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People. In this document the U.S. bishops pledged "to act in a way that manifests our accountability to God, to his people, and to one another in this grave matter."

Contrary to their pledge, few bishops have been held accountable for harboring abusive priests from the law. Neither the Vatican nor the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has taken steps to hold bishops accountable in a systemic way, let alone to hold a truth commission. Rather, these officials and their predecessors remain responsible for the fact that many former abusive priests who should be in monitored, mental health environments are walking free today.

[Nicole Sotelo is the author of Women Healing from Abuse: Meditations for Finding Peace, published by Paulist Press, and coordinates WomenHealing.com. She is a graduate of Harvard Divinity School.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time a Young Voices column is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.