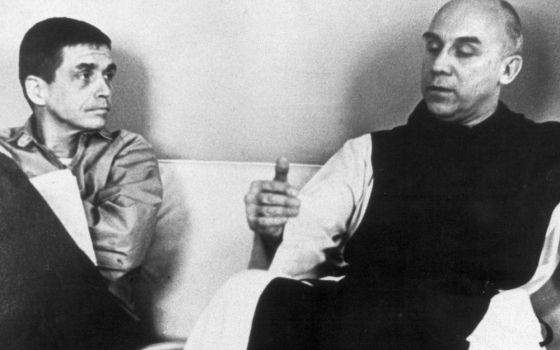

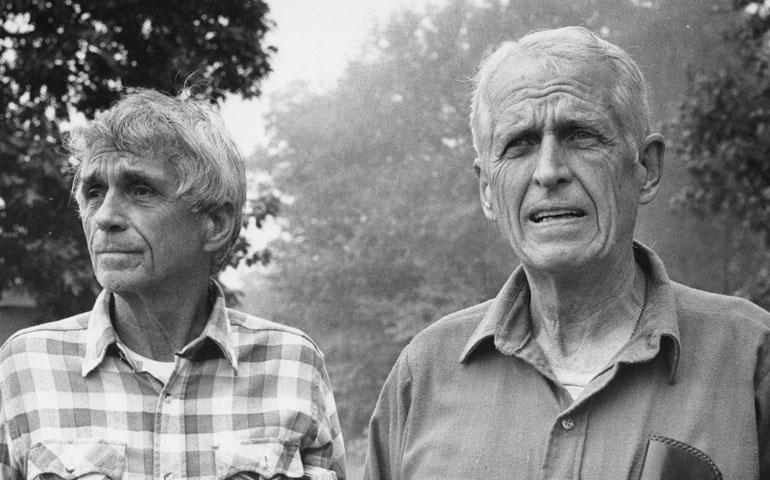

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, left, and his brother Philip in 1985 (NCR photo/Walter Walden)

THE BERRIGAN LETTERS: PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN DANIEL AND PHILIP BERRIGAN

THE BERRIGAN LETTERS: PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN DANIEL AND PHILIP BERRIGAN

Edited by Daniel Cosacchi and Eric Martin

Published by Orbis Books, 340 pages, $30

Editor's note: When we asked Colman McCarthy in mid-April to review this collection, we could not have anticipated that this piece would be pegged by the news of Daniel Berrigan's death at age 94 on April 30. McCarthy reflects further on Berrigan's life in the accompanying column below.

They were a band of brothers, Daniel and Philip Berrigan, twinned not by birth but by a shared commitment to resist the militarism of the state while affirming the personal power to live lovingly and spiritually. Beginning in 1939, when Daniel was a teenaged novice in a Jesuit seminary in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and Philip a free-spirited high school basketball player, the brothers put pen to paper for nearly seven decades until death came for Philip in 2002.

Of the nearly 2,200 Berrigan brother letters stored at Cornell University and DePaul University, fewer than a quarter were culled for these pages.

What emerges first in the epistolary prose is the intensity of love each brother had for the other. In April 1966, Philip, then a Josephite priest and soon to engage in his first of multiple acts of nonviolent civil disobedience against the American war machine that would lead to 15 years in jails and prisons, offered birthday greetings:

My love and respect for you grows with the years. I recall you remembering a few great priests in your life, and how they influenced you. For me there has been but one, and it is graphically and emphatically you. If this were all the Lord chose to give me, it would be enough, but the hundredfold is also there with you, but mostly because of you.

And with this comes the explicit confidence that as the plot thickens in these mysterious times, there will be one clear voice to listen to, and a great heart to join.

In October 1987, it was Daniel hailing Philip:

Dear Brother, I couldn't think of a gift to send you for your birthday -- then I thought of this scrawl, it tries to say what can't be said -- what you mean to me, a gift every year of your life presses down and overflows more and more wondrously.

"Thank you for your verve and good humor and a heart big as the world, and beautiful as we long to make the world. Thank you, not for 'not giving up,' which says nothing of keeping at it; as you do with style and celebration and a single eye on the 'one thing necessary.'

Some letters began with "Dear Bruv," others "Dearest Bro." Some sign-offs: "Love you, lean on you." "Peace of Christ." "You make the days and nights bearable."

Yet amid the warmth were moments of coldness, even harshness, as in a 1989 exchange of letters when a rankled Philip said that he and wife, Elizabeth McAlister, "listen to you with attention, relish, gratitude. You don't listen that well to us, creating a frequent impression condescending and patronizing. ... Perhaps I'm off the wall in this, perhaps I'm stumbling over my own ego, allowing my 'feelings' to create false issues, even unjust ones. If so, tell me."

Daniel replied a week later in a lengthy letter: "Over the years, I've seen myself perforce as a listener and learner in your regard. This has not always been easy for me, but I've taken that stance, since your opinions on people, politics, peacemaking, etc., are usually offered not as occasions for discussion but as incontrovertible. I seldom if ever feel invited to offer something about my work, my community, my troubles, -- nor do I often gain the impression I have something to offer. So I clam up."

The smogged air would clear, and soon after Daniel signed off a letter with "love, warmth, light, hope."

For those who followed the lives of the Berrigan brothers, whether as admirers and supporters or as critics who saw their protests as capers and street theater, the letters serve as backdrops to their prehensile ministry that included faith-based service and writing. Philip's books include Fighting in the Lamb's War, A Punishment for Peace and Widen the Prison Gates. Daniel's lithe and metaphorically rich prose is well displayed in his more than 40 books.

From 1990 to 2002, their letters occasionally tended toward the chatty. Daniel recounted his sadness over the death of the poet Denise Levertov, hearing from peace activist Mairead Maguire, being interviewed by the "intelligent and compassionate" journalist Amy Goodman, catching up with St. Joseph Sr. Helen Prejean.

The flow of the letters could have moved more smoothly had the editors laced them with footnotes. When Daniel or Philip make references to allies on the barricades like Arthur Laffin, Tom Fox, Fr. John Dear, Jesuit Fr. Steve Kelly, Oblate Fr. Carl Kabat, Ed Guinan, Jesuit Fr. Richard McSorley and Mitch Snyder, a line or two of descriptive identification would help illuminate readers not as well in the know as they might be.

The final letter from Philip to Daniel was on Nov. 10, 2002, weeks before Philip's death in his 79th year in the Baltimore commune, Jonah House, that he oversaw with McAlister.

Ailing, he said it's "all downhill now, mostly coasting. I'm leavin' behind some good people."

There was truth in that. Daniel and the pack were all plowsharers.

[Colman McCarthy directs the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington, D.C. His recent book is Teaching Peace: Students Exchange Letters With Their Teacher.]