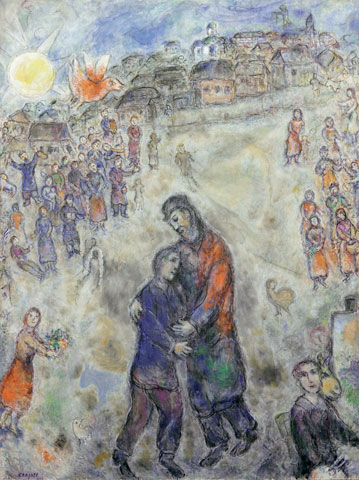

"The Prodigal Son" (1975-76) by Marc Chagall (Newscom/akg-images)

SHORT STORIES BY JESUS: THE ENIGMATIC PARABLES OF A CONTROVERSIAL RABBI

SHORT STORIES BY JESUS: THE ENIGMATIC PARABLES OF A CONTROVERSIAL RABBI

By Amy-Jill Levine

Published by HarperOne, $25.99

Years ago, in a literature course that I taught at a community college, I opened a discussion of the short story chapter with the first reading in the classic anthology Structure, Sound, and Sense, "The Prodigal Son." My night class of primarily middle-aged, working-class women was normally very engaged and participatory, which gave me great satisfaction, because I knew that at least half of the students would go directly from class to their jobs cleaning offices and tending to patients at local nursing homes. But before I could raise such formal issues as plot, characterization, structure and irony, a student said, "This isn't fiction; it's the truth."

Stunned to awkward silence, I recognized that I was forcing my students to abandon their customary, reverential reading of sacred Scripture, and rediscover "The Prodigal Son" as a mere story.

As provocative as this secularized reading was to my students, the discussion eventually reached the key lesson: that this, like all of Jesus' parables, is an allegory — a symbolic narrative — in which, in my reading, at least, the father stands for the ever merciful and forgiving God, and the two sons represent ways in which God's children go astray. Initially alarmed, my students were ultimately comforted by the direction of the discussion: The story had been tamed, and their original interpretation validated.

But I hadn't considered an even more challenging way of reading: What happens when we read this parable literally, forsaking the traditional effort to allegorize? What if the father and the sons are merely that, and the father, who appears to overdo it in his effort to supply the younger son with a lavish reception, is truly the prodigal? What if this parable, and all such stories that Jesus tells to his disciples, is not meant to confirm our preconceptions and reinforce traditional Christian doctrine, but rather to provoke, disturb and force us to question our assumptions?

These are the questions that Amy-Jill Levine poses in Short Stories by Jesus. Levine, professor of New Testament and Jewish studies at Vanderbilt University, challenges us to reread the parables and to resist the traditional interpretations (including the contextualizations of the evangelists themselves) that "domesticate" these stories and blunt their intended impact. Only by opening these texts to reinterpretation can we recover Jesus' difficult, sometimes disturbing, yet keenly relevant lessons.

Levine's painstaking analysis not only frees the parables from their customary readings, but also convincingly argues that the parables are gloriously open-ended, impossible to pin down, and therefore living, vibrant texts.

If most Christian readers have accepted parables as comforting allegories, Jesus' Jewish listeners certainly did not. Levine's argument rests on her contention that we can embrace the challenge of the parables only if we see them in their original context, and Levine strives to recover that context and thereby enable us to read the parables, and Jesus and his mission, in nontraditional ways. Jesus' Jewish listeners did not hold shepherds in high esteem, nor did they necessarily disrespect merchants, judges and Pharisees. Jesus and his Jewish listeners were concerned not about the afterlife as much as they were concerned with their daily lives, and the parables, read in their context, reveal a pragmatic rabbi conveying practical lessons.

Jesus' disciples would understand the vineyard owner not as a symbol of God, but as a vineyard owner, albeit one who hires all who need work and pays a living wage to all workers, whether first or last hired. Reading thusly, argues Levine, treats the parables properly, as provocative texts that challenge us to treat others fairly in our immediate communities, "to act as God acts, with generosity to all."

Most importantly, when we read Jesus' parables in their original context, we must abandon the persistent and destructive anti-Semitism of many traditional interpretations.

Why, Levine asks continually, would a Jewish rabbi tell anti-Semitic stories to an audience of Jews? How could Jews possibly accept, let alone understand, a lesson that is really supposed to debase them and glorify gentiles? Levine reviews and rejects the many interpretations of the parables that strain the meaning to vilify and stereotype Jews, arguing that Jesus was not interested in persuading Jews to abandon their faith, but to live peacefully and lovingly with all faiths. As Reza Aslan does in Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, Levine reveals that by historicizing Jesus life and teaching, we undermine the basis for centuries of hatred and oppression.

Levine's book is a fascinating hybrid. On the one hand, Short Stories by Jesus is a scholarly text that critiques traditional and contemporary exegetical readings of a specific parables, and then engages in nearly line-by-line analysis of these parables, reconsidering translations from the Greek, finding scriptural analogues, and drawing liberally from various rabbinic texts.

Yet Levine's book is also homiletic, encouraging readers to accept the challenge not only of a resistant reading of the parables, but also to accept the challenge to our values and conduct that these new readings pose.

Finally, it's also an entertaining read, peppered with pop culture references and seasoned with wit. Sometimes Levine's efforts at punning seem to undermine her more serious purpose, but we can forgive a quip like the one that states that the parable of the leaven "should get a rise of out its hearers, but in order to experience this, we need to clean our palates of both the bland, white bread interpretations and the toxic ones as well" as a welcome break from the more serious prose.

Overall, Short Stories by Jesus is a valuable work of criticism that asks us to reimagine Jesus as teacher who is concerned about the lives and the conditions of his followers, not merely in the condition of their souls in an afterlife. The parables, Levine argues, are about this world, not the next, and in that regard they have much to say about how "how to live in community; how to determine what ultimately matters; how to live the life that God wants us to live."

[Dennis McDaniel is associate professor and chair of the English department at St. Vincent College.]