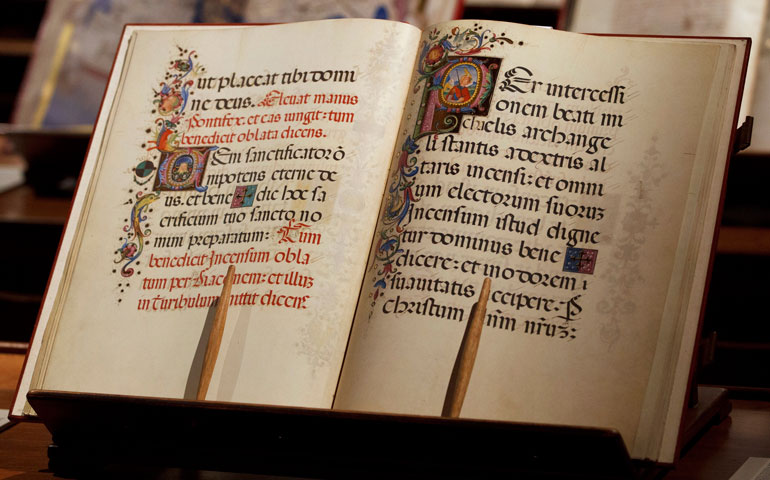

A copy of the Borgianus Latinus, a missal for Christmas made for Pope Alexander VI, is displayed in an exhibit on the Vatican Library. (CNS/Paul Haring)

THE FUTURE OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH WITH POPE FRANCIS

THE FUTURE OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH WITH POPE FRANCIS

By Garry Wills

Published by Viking, $27.95

In an interview for NCR in 2008, Garry Wills told John L. Allen Jr. that he was through writing about the church -- a promise he did not keep.

Rather, in 2013, he produced his most problematic tome, Why Priests?: A Failed Tradition, in which he argued that since the early church did not have priests from the beginning, it follows that there is no reason for them now. He also argued that the sacraments, alleged to have been instituted by Christ, sprouted up centuries later, each one intended to establish a clerical class to control faithful Christians. Most disappointing was his apparent dismissal of the presence of Jesus in the Eucharist.

The Future of the Catholic Church with Pope Francis, which says little about Pope Francis, can present itself as Catholic Teaching Not to Be Believed, by a Believer Who Has Done His Homework.

Having knocked off the priesthood, Wills turns his sword on certain beliefs, some of which have been reformed, but whose influence lingers in the dark corners of chanceries. These include:

- The role of Latin in clerical education and the liturgy, a form of intellectual imprisonment;

- The exaggerated stories of Christian persecutions and the "pathological yearning for martyrdom";

- The role of Constantine in running the church, even when he was not a Christian;

- The exaggerated role of Peter, who was not the first pope;

- The academic isolation of the American Catholic church and the persecution of Jesuit Fr. John Courtney Murray;

- The prevalence of anti-Semitism and the Second Vatican Council's courageous response;

- The failure of natural law to produce a credible set of principles to guide modern sexual morality;

- The refusal to ordain women;

- The absolute banning of abortion when there are cases when it should be allowed.

That's quite a list. Yet Wills speaks not from left field, but from inside the church, a regular Massgoer with a devotion to the rosary, whose sources include, along with St. Augustine, leading Catholic scholars: Murray, John Noonan, Raymond Brown, Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, Peter Hebblethwaite, John Henry Newman, John O'Malley, Gregory Baum, John Connelly, J.N.D. Kelly, Eamon Duffy, Peter Brown, Candida Moss and Joseph Fitzmyer.

Many of his points are familiar to scholars, but not to the faithful. Why? Perhaps because, as he says, in the training of priests in liturgy, Scripture and theological literature, the language was Latin, a mysterious cloud to which only the power people had access, and that kept the ordinary believer enchanted and ignorant.

With Latin as an instrument of clerical control finally dead and with Francis at the helm, how, according to Wills, might things change?

The attitude toward authority that allowed the magisterium (basically, the pope) to declare doctrines "infallible," like the Immaculate Conception of Mary, without reference to the Bible and without the full consent of the faithful will, Wills hopes, be replaced by the Word Incarnate, Christ living in the body of the church, vivified by both Scripture and tradition.

On the cult of the early Christian martyrs, he reports, there are no records of any Christians being put to death in the Colosseum, and over the course of 300 years, there were only 12 years of persecution.

In fact, although they were often linked as figures of authority, we know nothing about how Peter and Paul died. Yet Wills suggests Nero executed Paul for arson.

He also proposes that believing Jesus would endow one man with sole power to determine the whole future of the church is absurd. Rather, in "Thou art Peter and upon this rock ..." (Matthew 16:18), "Peter" represented the whole community.

The supposed list of early Roman bishops, which does not include Peter, is based on hazy memories and an occasional made-up name, and the idea of the pope as a universal leader did not come until the 11th century.

Wills' basic theme here is the church's abuse of its power, exemplified in the union between church and state during the Crusades, and in the countless rules limiting what one may read (the Index of Forbidden Books), write or say.

He recounts the heartbreaking scene where Murray, silenced by the Holy Office because he defended America's religious pluralism and the separation of church and state, mournfully cleared all his books on church and state from his library shelves.

Of course, Murray eventually triumphed as an adviser at Vatican II, which enshrined his philosophy in its decrees.

Vatican II likewise overcame the church's deplorable history of anti-Semitism with the help of "Jewish priests and theologians who had become Christian priests and theologians," Wills writes.

The council's document Nostra Aetate proclaimed, "The Jews remain very close to God ... God does not take back the gifts he bestowed or the choice he made."

Wills' point: "The church can live because it can learn, correct, and change under God's direction."

The final chapters, built around natural law, take on sexual morality, especially contraception. He tells the story of the pope's birth control commission, which overwhelmingly advised that contraception should be permitted. The commission was overruled by Pope Paul VI, under the influence of Jesuit Fr. John Ford.

Wills refutes the arguments against women priests and, passing over the horror of late-term abortion, tolerates early abortion under certain circumstances.

His last pages extol the indispensable virtue of forgiveness, while rejecting the negative elements in the history of the sacrament of reconciliation. As far as he is concerned, the sacrament is dead. That millions have found and continue to find this sacrament of forgiveness in its new forms a source of peace and encouragement seems to have escaped him. For this -- and other faults -- we will have to forgive him.

[Jesuit Fr. Raymond A. Schroth is the literary editor of America.]