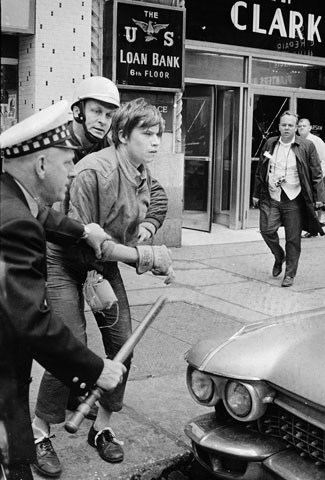

Two policemen arrest a member of the Weathermen during an Oct. 11, 1969, march in the downtown Chicago area. (AP/Fred Jewell)

DAYS OF RAGE: AMERICA'S RADICAL UNDERGROUND, THE FBI, AND THE FORGOTTEN AGE OF REVOLUTIONARY VIOLENCE

DAYS OF RAGE: AMERICA'S RADICAL UNDERGROUND, THE FBI, AND THE FORGOTTEN AGE OF REVOLUTIONARY VIOLENCE

By Bryan Burrough

Published by Penguin Press, $29.95

The Vietnam anti-war movement of the 1960s and 1970s was a mixed bag, populated by individuals who were pacifists, socialists, activists, young, old, mainly white -- but with strands of people of color, since its roots, though tangled, were deep in the civil rights movement that preceded it.

Days of Rage, though, is not mixed at all. It covers only the violent side of the anti-war movement, beginning in 1969 with Sam Melville, "the man who started it all," a white, 30-something, long-haired New York City bomber, famously gunned down two years later during the Attica prison revolt. It's a curious place to begin, but one must start somewhere.

Bryan Burrough has published five other books, three covering financial figures, one on NASA, another on the early years of the FBI. He is an odd author to tell this tale, given his attachment to the magazine Vanity Fair. Vanity Fair has perfected a sort of celebrity journalism featuring the rich and the powerful behaving badly. There's a lot of that going on.

Days of Rage doesn't escape Vanity Fair's personality-centric style. The book lists a "Cast of Characters," 54 people, members of six groupings that Burrough assembles, such as the Weather Underground, the Black Liberation Army, the FALN (Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional Puertorriquena), and others, some little-known.

Given the span of history the book covers (roughly late '60s through the early '80s), this is actually a small amount of people. Burrough seems to ascribe to the theory that history is driven by individuals, rather than so-called larger forces.

Indeed, Burrough's object is to write a "straightforward narrative history of the period and its people." He means to keep his judgments "to a minimum." Earlier, he criticizes John Castellucci's dense book on the Brink's robbery of 1981, The Big Dance, for being "so loosely structured it is often hard to follow."

The world of the not loosely, but tightly, structured straightforward narrative is meant to be fast-read history -- if any book of nearly 600 pages can be said to be read fast. A number of odd revelations stand out with this method. Burrough alternates white groups followed by black groups and Puerto Rican groups (the FALN), then mixed racial groups, concluding with the strange (though all the stories are strange) account of two white couples, plus children, merry bombers and eventual cop killers.

Being so schematically structured, Days of Rage presents the white/black/Puerto Rican worlds as separate, occasionally invaded by the practically all-white FBI, and other law enforcement groups with sparse minority representation, looking for the diverse underground perpetrators. Burrough thus sets up, perhaps unconsciously, a weird race-based story.

Succinctly put (which he seldom attempts, brevity not being his strength), he shows that, for their sessions of radicalization, the white radicals went to college, the black radicals went to prison, and the Puerto Ricans did a bit of both.

That's the trouble with fast-read history: It often leaves out nuance. Burrough's cause for all the depicted mayhem is the white students' guilty solidarity with black struggles: "What the underground movement was truly about -- what it was always about -- was the plight of black Americans."

He downplays the Vietnam War, the draft, etc., but the history is more complicated than he allows. He never notices, it seems, that righting wrongs heaped upon black Americans was not so much the reason for the conduct described, as it was a justification. Not coming from the generation he writes about, Burrough misses other motives, including the effect of World War II's Holocaust, fitfully revealed as these kids grew up, on their consciences.

So, beyond the great "man" theory of history, we get the violent theory of history, which is that nothing of importance happens in the world without violence. It's the "American as cherry pie" analysis of social change.

His book has been assembled from research, other people's books, a lot of memoirs, and a few important interviews he undertook with prominent movement veterans.

This is the method of magazine journalism, yet Burrough's most important contribution is those interviews -- especially the ones with Liz Fink, a radical lawyer active since the late 1960s; Cathy Wilkerson, the Weatherman who survived the 11th Street townhouse explosion in 1970; Ron Fliegelman (Burrough's chief scoop), Wilkerson's partner in crime and father of her child; and a few peripheral others, plus a handful of talky former FBI agents.

I was surprised Burrough, as a writer of three books dealing with the modern financial world, didn't have any sort of political economy analysis to offer. Why were all those college kids able to drop things and run off to protest, in both the civil rights arena and the anti-war movement? He still doesn't seem to know.

It's the economy, stupid. The '60s and early '70s still had enough surplus capital floating around to allow for youthful leisure, this being before Ronald Reagan made sure all that money went into the right hands. It's one of the larger forces Burrough neglects.

Burrough keeps saying throughout, in one version or another, that the world the underground bombers occupied began to "change." No one cared anymore; "America yawned."

The book ends with a where-are-they-now epilogue. I enjoy that sort of thing as much as anyone, but still there is no hard reckoning of how the world changed. That might have forced the author to make "judgments."

Days of Rage is full of period highlights and if one is well-versed in the history Burrough doesn't cover, it's easy to add context. (The name Berrigan isn't found in the index or the text; though Burrough refers once to the "Catholic underground," that also missed the index.)

Fresh ruminations, though, can arise from his depictions. First, that the black violent revolutionaries were among the first to be globalized, to travel abroad, to see their plight in a geopolitical context.

Second, that as the underground and the bombings continued over the decade of the 1970s, women became more central, yet remained at the beck and call of the men. This volatile internal dynamic finally helped implode the remaining straggling violent groups.

Days of Rage is heavy on facts and light on analysis, and readers not familiar with this material will read it chiefly as a lurid tale, a text-movie unspooling before their eyes: the sexual revolution as adapted by radicals, the boyfriend/girlfriend world of political motives and decisions, the fun of blowing things up, thrills and chills, the Patty Hearst circus revisited once again, wild ironies on display and jaw-dropping episodes of coincidence, how drugs fueled so much of the late violent manifestations, and all along the "feckless" FBI fumbling through. Burrough, preposterously, speaks admiringly of J. Edgar Hoover, but the FBI doesn't come off well, as usual, in this account.

However flawed, I hope Days of Rage secures a wide readership, especially among the uninformed young.

Burrough's central thesis is all this past has been "forgotten." But by whom?

America's talent for forgetting can be salubrious. The problem is not what we forget, but what we remember. That propensity produces many grim examples, one being what the recent Confederate-flag-waving young killer Dylann Roof chose to remember in Charleston, N.C. He murdered nine -- no radical bomber in Days of Rage killed nine people at once. Look out for what you remember.

[William O'Rourke is an emeritus professor of English at the University of Notre Dame and the author of The Harrisburg 7 and the New Catholic Left. His most recent book is Confessions of a Guilty Freelancer.]