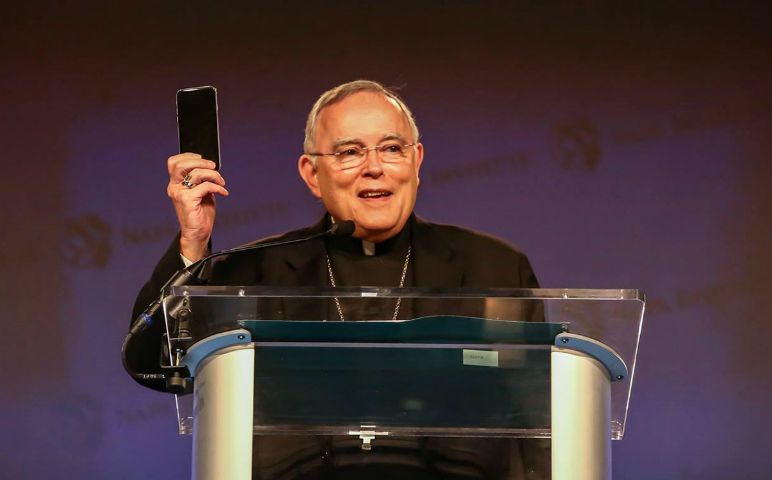

Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput speaks during the July 27 opening of the seventh annual Napa Institute Conference in California. The conference this year was organized around the themes discussed by Archbishop Chaput in his book. (CNS photo/courtesy Kate Capato, Visual Grace)

STRANGERS IN A STRANGE LAND: LIVING THE CATHOLIC FAITH IN a POST-CHRISTIAN WORLD

STRANGERS IN A STRANGE LAND: LIVING THE CATHOLIC FAITH IN a POST-CHRISTIAN WORLD

By Charles J. Chaput

Published by Henry Holt and Co., 288 pages, $26

Archbishop Charles Chaput's new book, Strangers in a Strange Land: Living the Catholic Faith in a Post-Christian World, is strange indeed. Strange in its almost relentlessly pessimistic view of America today. Strange in its sweeping claims. And, perhaps strangest of all, the book leaves the reader wondering why a bishop would feel compelled to pen such a thing, reliant as it is on virtually every right-wing thread of cultural and political analysis.

To be fair, the book has some high points. Toward the end, Chaput quotes one of my favorite observations of the great Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar: "The Church must be open to the world, yes: but it must be the Church that is open to the world. The body of Christ must be this absolutely unique and pure organism if it is to become all things to all men. That is why the Church has an interior realm … so that there is something that can open and pour itself out." Chaput links this nicely to Pope Francis' observation that the church isn't an NGO or a social club.

Elsewhere, Chaput writes that "we tend to think of works of charity separately from the Mass, but for the early Christians the two were tied intimately together" and he rightly offers the hope that we recover the linkage. And when he writes, "In effect, we don't possess joy; joy possesses us," I find myself nodding in agreement.

Alas, the fine points in the book are usually overwhelmed by sweeping claims. Here are a few for example:

- "We live in a time when the product of man's reason — the creature we call science — now seems to turn on and attack reason itself, to discredit free will, and to diminish anything unique about what it means to be human."

- "Americans hate thinking about the past."

- "Consumption is a private affair. It requires only the self."

- "But in a technocratic culture — what the media scholar Neil Postman called a 'technopoly' — technology is its own justification. It's the driving force of life."

- "American life is a river of noise and pressure, a teeming mass of consumer appetites."

- "Many of us are happy to live with half-truths and ambiguity rather than risk being cut out of the herd. The culture of lies thrives on our own complicity, lack of courage, and self-deception."

- "God has never been more cast out from the Western mind than he is today."

This last quote points to another disturbing fact about the book. It makes some claims that are not just sweeping, but also wrong. Does the archbishop really believe that God is more "cast out" from the Western mind than God was in, say, 1942?

Chaput writes: "Just as modern feminism depends on the technological conquest of the female body — the suppression of fertility — so, too, [Michael] Hanby argues, same-sex marriage depends on the technological mastery of procreation." Again, sweeping, wrong, and even offensive. If the pill had never been invented, there would still be modern feminism.

Some of Chaput's assertions are less sweeping but involve the kind of cultural analysis that is bizarrely right-wing. "A brief glance at the twentieth century destroys the myth [of progressivism]," Chaput writes. "In just a few decades, 'progressive' regimes and ideas produced two savage world wars, multiple murder ideologies, and the highest body count in history." Huh? What was "progressive" about Hitler and Mussolini? Stalin claimed the mantle of progressivism but it was a sham, as even the Old Bolsheviks quickly realized.

Or consider Chaput's take on the presidency of Barack Obama. "The White House elected to power in November 2008 campaigned on compelling promises of hope, change, and bringing the nation together," he observes. "The reality it delivered for eight years was rather different: a brand of leadership that was narcissistic, aggressively secular, ideologically divisive, resistant to compromise, unwilling to accept responsibility for its failures, and generous in spreading blame." I am no cheerleader for Obama, but that is all nonsense. Does not Sen. Mitch McConnell share at least some of the fault for the resistance to compromise? Indeed, did not Chaput himself, who loudly proclaimed Obama unfit to speak to the graduates at the University of Notre Dame in 2009, deserve some of the blame for the divisive quality of politics and culture in the past eight years?

Chaput repeats his correct assertion, "If we don't love the poor, we will go to hell." But at other times, his ideological bent obscures whatever experiential knowledge of the lives of the poor he may have acquired over the years. "The post-Christian developed world runs not on beliefs but on pragmatism and desire," he writes. "In effect — for too many people — the appetite for comfort and security has replaced conviction." Alas, for many indigent people, the appetite for comfort and security is real, not least because it is so often frustrated.

Later, Chaput approvingly quotes James Poulos on the subject of private property ownership: "Buying means responsibility and risk. Renting means never being stuck with what you don't want or can't afford. … There's something powerfully convenient about the logic of choosing to access stuff instead of owning it." Convenient? There are plenty of poor folk who would love to own property. They know it is the key to economic stability. Chaput's conservative cant clouds his ability to see reality and makes his words obtuse.

There is much about contemporary culture that should disturb a Catholic. When was this not so? When Christianity learned to live with slavery? With the submission of women? With genocidal regimes? Did everything really just get ugly when couples started using contraception and gays and lesbians asked to be married?

It is not clear to me why a bishop would write a book like this. It has some Scripture references and some citations to Augustine and other respected theologians, but ultimately this is the work of a frustrated political commentator, maybe even a blogger. If Chaput thinks his shallow, sweeping cultural analysis needs to be heard, why not resign his post and apply to First Things for a job as a columnist? I am sure they would hire him. This book will confirm the prejudices of those who watch Fox News. If you believe what Chaput writes, this book will make you depressed. What he writes is not persuasive, and this book is best left unread.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]