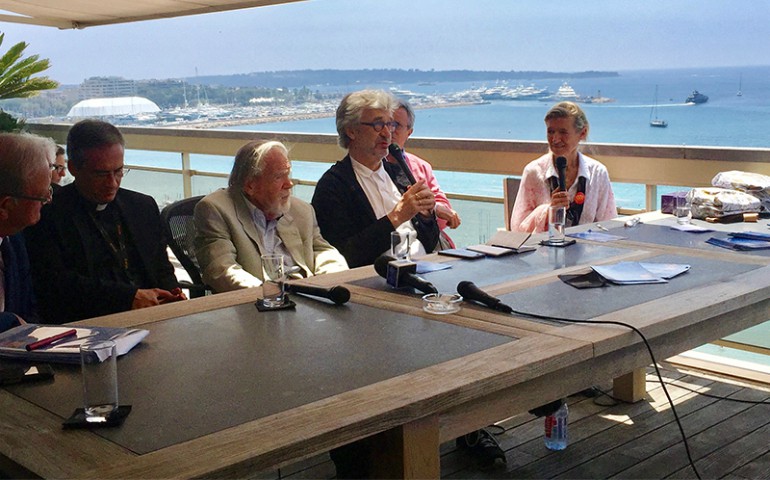

German director Wim Wenders, center, speaks during a panel discussion on May 25, 2017, in Cannes, France. (RNS/A.J. Goldmann)

When films by Fellini and Rossellini topped the list of Pope Francis' favorites, it should have been clear that, when it comes to cinema, this is an unusually discerning pontiff.

Francis recently granted a series of film interviews with legendary German director Wim Wenders that form the basis of "Pope Francis — A Man of His Word," an in-depth documentary that was acquired last week by Focus Features at the 70th Cannes Film Festival.

Last week, Wenders put in an appearance at Cannes, along with his friend the Rev. Dario Edoardo Viganò, to take part in the Festival Sacré de la Beauté, a celebration of religion and art that has occurred alongside the film festival for the past four years.

Viganò is the prefect of the Vatican's Secretariat for Communications, a title bestowed on him by Francis in 2015. Appearing in Cannes for a whirlwind 24 hours, Viganò was the Vatican's first-ever envoy to the world's most famous — and glamorous — film festival.

Wenders, 71, met the monsignor at the 2004 Venice Film Festival, where the director was receiving the Vatican's Robert Bresson Prize for "testimony, significant for sincerity and intensity, of the difficult passage in search of spiritual meaning in our lives." The two have remained close friends. At Viganò's suggestion, Wenders consented to be the Festival Sacré de la Beauté's guest of honor.

On Ascension Thursday (May 25) — day nine of the film festival — a full-day program devoted to spirituality and cinema kicked off with Mass at the Church of Notre Dame de Bon Voyage: Cannes' central Catholic church, a stone's throw from the Palais du Cinéma, the film festival headquarters.

After services, Wenders and Viganò sat down to a roundtable with journalists, clergy and politicians held at the Palais d'Orsay, from a balcony that commanded stunning views of the Mediterranean.

"Film time is always very condensed life time," Wenders said over gourmet finger food and glasses of rosé. "You work for maybe three years on a movie and then you see it for 90 minutes or 100 minutes, so it better be worth it," he explained. As a filmmaker, he continued, you need to justify your projects from that point of view.

"It's not so much the story, but something more essential, which is: Why are we here and what are we living for? In a strange way, every movie has to respond to that. And if you're a man of faith like I am, who believes we are watched by a God who loves us, then a movie sort of has to reflect that. And if it doesn't, then what did I do for three years?" he reasoned.

After the roundtable and a light lunch, Wenders and Viganò made their way to the American Pavilion, a meeting place for industry insiders, for a panel titled "Making Movies that Matter."

They were joined by Anne Facérias, founder of the Festival Sacré de la Beauté, and moderator Bruno Chatelin, founder of filmfestivals.com.

The film industry is not exactly known as a bastion of religious sentiment. But Wenders and Viganò's words resonated with what seemed to be a mostly secular audience.

"As a filmmaker I can tell you, you cannot intend to make a film that matters," Wenders explained, adding that many supposedly important films turn out to be totally insignificant.

"But sometimes this miraculous thing happens, that a film that is dear to someone's heart, like the filmmaker's, becomes dear to other people's hearts and all of a sudden, the fact that it matters appears as something that you do together — the audience as well as the filmmaker — and that you feel together. So I think the only thing that matters is these miraculous agglomerations of happiness and of meaning.

That's when you've touched on something that touched the audience and that the audience needed at that moment," Wenders continued.

On his website, Wenders lists some of his favorite films, including Jean Renoir's "The Rules of the Game," and Yasujiro Ozu's "Tokyo Story." Neither is religious or spiritual in a conventional way. But their deep humanity and artistic sensitivity transmit insights into what it means to be alive.

"You see the thing that matters, not because it's thrown at you, but because you can discover it," Wenders said, giving a word of warning against trying too hard to convey messages in films.

As much as a director is obligated to choose films with care, Wenders added that sometimes films choose their directors. "If you don't feel you're the only person who can make a film, then you better not touch it," he said. "If you really feel like that subject wants you and needs you, you need to answer to that responsibility."

These might seem drastic criteria for success in filmmaking. Wenders matter-of-factly admitted that not all his films have really mattered. Maybe not, but he has made enough that have, including masterpieces such as "The American Friend" (1977), "Paris, Texas" (1984) and — arguably his most famous film — "Wings of Desire" (1987), about angels watching over a still-divided Berlin.

"Wim makes films that move both the heart and the mind deeply," Viganò offered in Italian, adding that their friendship has helped Viganò understand how Wenders' films reflect the director's soul.

St. Benardino of Siena is the patron saint of advertising and public relations. St. Clare of Assisi is the patron saint of television. Viganò lamented that cinema does not (yet) have a patron saint.

To fill this vacancy, Viganò proposed the angels: the angels of the Bible, of Dante, of Rilke and, yes, of "Wings of Desire." "Angels are made of light and movement, exactly like cinema," Viganò clarified to a mixture of applause and laughter.

The director seemed flattered, but also a bit uneasy about being in such illustrious company.

"Coming up with a film in Berlin more than 30 years ago, I invented characters for a movie that were drawn a lot, yes, from the Bible and from Rilke. But I thought they were fictional characters, outrageously fictional. And then I made the movie. I had no clue how to make it. I made it without a script. And every day I got help, miraculously. And slowly I understood that these angels had their fingers in there: that they were giving me an incredible gift and I could only accept that I had to receive it and pass it on.

"So I refuse any responsibility for ‘angel activity' in this festival or anywhere else. But I was blessed to get to know them a little bit," the director finished. "And I hope that all of you sometimes have that experience."