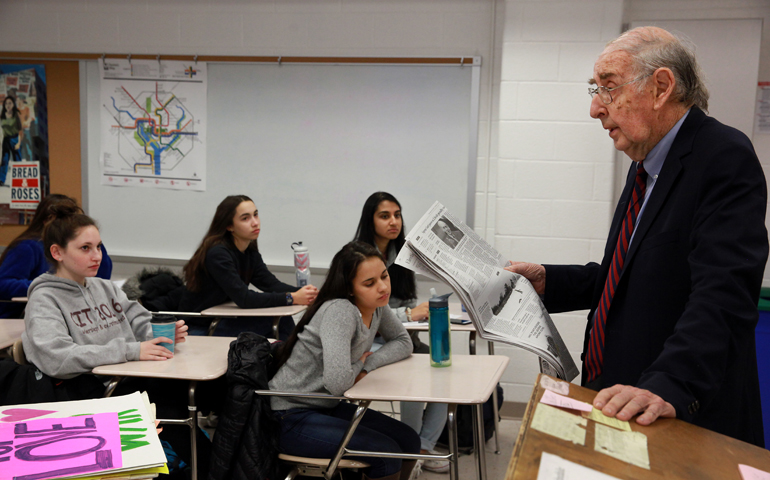

Colman McCarthy, Dec. 13 at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School in Bethesda, Md., where he teaches two morning classes five days a week on peace studies. (Rick Reinhard)

Colman McCarthy has a standup bit that he regularly uses to make his case. He takes a crisp $100 bill out of his wallet and folds it in the middle so it will stand on end.

In a recent version, he placed the bill on a desk in front of a packed classroom at the prestigious Georgetown University. Then he announced the challenge: Whoever can answer all of his questions will get the $100.

He has done this for years. It's been videoed and broadcast.

It starts off easily enough. Who was Robert E. Lee? Napoleon? Ulysses S. Grant? And the answers come back quickly, visions of $100 dancing in heads, even those of students at this upscale Jesuit university.

And then come the stumpers: Emily Balch? Jody Williams? Jeannette Rankin?

Silence.

Everyone knows the warriors. Few are familiar with significant peacemakers.

The Ben Franklin goes back into the wallet. He’s never had to pay out.

The punchline: It’s not the students' fault. It’s the education system. They should go back and sue the school districts for a failure to educate, he jokes. But the point is made — we've all been taught in traditional curricula a lot about wars and generals; we've been taught almost nothing about peacemakers and the effectiveness of nonviolent force.

In the abstract, the line "Let's teach kids how to make peace," seems almost too obviously logical to require discussion. In reality, McCarthy has learned, it is a topic that is rarely wedged into the normal school curriculum.

Poking at presumptions

McCarthy has made a vocation of poking at the culture's presumptions, and that contrarian streak extends to his appearance. The tall, lanky, teetotaling vegan who even abstains from coffee hardly looks the part of a revolutionary. He rides a Raleigh three-speed bicycle to most of his teaching assignments, this year at three universities, a law school and a high school. At age 78, he still sneaks off whenever he can to get in a round of golf.

McCarthy (NCR photo/Tom Roberts)

He laughs often, but in reserved "ha, ha, ha" syllables. A professional storyteller for much of his life, he's always got one, sometimes told through the hint of a stammer that nearly paralyzed him as a youngster and compelled him toward what he imagined as the quiet life of a writer.

He grew up on Long Island, the son of John and Lucy McCarthy, an immigration lawyer and a stay-at-home mom, both children of Irish immigrants, who reared four sons. He was the beneficiary of a certain level of privilege. His father was club champion at Brookville Country Club on Long Island, and passed the golf gene, as well as a home practice course, onto his youngest son. His father had groundskeepers from his country club install four golf holes in the corners of their large square of property. The son ended up with a wicked short game that's never left him.

At the same time, McCarthy lived in a home that was often a first stop for refugees, people straight from Ellis Island. His father would get them jobs on estates out on Long Island, the McCarthy residence serving as way station on the path to integration into American society.

No doubt those beginnings had something to do with the trajectory of his life and his easy embrace of life's paradoxes. He more than embraces them, at times he creates them: the teacher who scorches the education system; the countercultural pacifist who for years made his living on the op-ed page of a cultural icon, The Washington Post; the religiously unaffiliated who was formed by ancient religious traditions and still draws deeply from those wells.

He has held a certain prominence for decades as an accomplished writer advocating countervailing social views. He’s carved out an unorthodox niche in some unlikely spots, and he’s used those various forums to push the notion that both peace and violence are learned behaviors — and that we should be far more interested in teaching the former than the latter. The reality, he would argue, is the reverse.

"What I have surety about," he writes in the preface to I'd Rather Teach Peace, "is that students come into my classes already well educated, often overeducated, in the ethic of violence. The educators? The nation’s long-tenured cultural faculty: political leaders who fund wars and send the young to fight them, judges and juries who dispatch people to death row, filmmakers who script gunplay movies and cartoons. Toy manufacturers marketing 'action games,' parents in war-zone homes where verbal or physical abuse is common, high-school history texts that tell about Calamity Jane but not Jane Addams, Daniel Boone, but not Daniel Berrigan."

When people suggest that he balance his course with "the other side," he responds that he is the other side, the balance to the culture’s incessant education about violence.

McCarthy's students Dec. 13 at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School in Bethesda, Md. Once a week, during class, the students go in front of the school on East West Highway to proclaim their beliefs. (Rick Reinhard)

The young writer

His journey has been both more than a touch quixotic and a bit Gump-ian. As a youngster, he stuttered so pronouncedly, he says, that he determined early on that he would be a writer. "They just go in a little room, shut the door, no one's going to know I'm handicapped. So that's when I kind of started. I read a lot, I expanded my vocabulary." And then there was a magical moment in the sixth grade.

Just back to school in September, the class was asked to do the classic essay on their summer. One boy experienced an early bout of writer’s block and quietly told the teacher that he couldn't get started. The teacher told him, "Go sit near Colman. He'll show you how to get started. He's a good writer."

"I overheard that," McCarthy said, "and I've been on a high ever since."

He read and wrote constantly, closed up in his room. He was developing a craft that would sustain him in the long run. But when he was 16, his world was upended. His father died of a heart attack in his sleep. "I had a very severe grief reaction," he said. "I just couldn't go back to school. I just couldn't get over it."

He said his father's death inspired his adherence to an austere diet and his passion for bike riding and running.

His mother suggested that he go to live with an older brother who was stationed with the army at Fort Benning, Ga., for his junior year of high school. He attended Baker High School in Columbus, Ga., for a year (coincidentally, McCarthy notes, the same school where, a few years later, Newt Gingrich spent his junior and senior years).

He came back to Long Island to finish out his high school career, during which he made "wretched grades. ... I was failing biology, I was failing mathematics, all I wanted to do was learn to write." An English teacher took him under his wing, and said he'd give him extra credit for extra assignments. "So I wrote about a thousand words a night. And he'd read it and slash it and say, 'This is garbage,' or 'this is okay.' " Good training for the years ahead.

Despite the academic struggles, he was accepted at Spring Hill College, a small Jesuit school in Mobile, Ala. By the time he graduated in 1960, he had also, with a 69 scoring average, played in two PGA tournaments as an amateur and was looking forward to joining the tour as a professional.

On the drive home from Mobile to Long Island, inspired by the writing of Trappist monk Thomas Merton, he stopped off at a Trappist monastery in Conyers, Ga., and "stayed for a few days to get my head back together again" and ended up thinking "Gee, why don't I give it a try?"

The abbot told him to go home and if he still wanted to after thinking it over, to come back and talk. "That was June, and I came back in August, and I stayed for five and a half years. And there went my golf game!" He was a lay brother — he took temporary but not final vows — and was assigned to the dairy crew. He helped with a herd of about 150 Jersey cows, milking them twice a day and shoveling manure, which, he jokes, he has come to see "as a good preparation for journalism."

He was eventually promoted to the kitchen, where he cooked for about 80 monks.

The life was cloistered and austere, but it was a rich time. He kept journals and he read hundreds of books a year. He studied language and writing techniques. He both benefitted from and tried to find ways around the rigid disciplines.

One way to get out of the cloister for a day was to donate blood. "I was so eager to get outside the walls that I became the Red Cross donor of the century," he said. "Every time we'd go to give blood, I'd run in and be the first in line." Finished with donating blood, he would spend the rest of his time in town at the news stand next door devouring magazines and newspapers.

The wise abbot realized after five years that McCarthy and monasticism were not a good fit, that monks who work so hard to find ways to escape the cloister should probably find a vocation on the outside. So he gave McCarthy a black suit and $50 and drove him to the airport. But not before the erstwhile monk had made a connection with an editor for the Atlanta newspaper who regularly visited the monastery. He told McCarthy that he had no positions for him at the paper, but had a friend at United Press International wire service in New York and would see what he could do.

That's how the golfer/writer/former Trappist wound up on the sports desk at UPI, mostly taking down results from horse racing tracks in the region. But the career didn’t last long, and he probably hastened the end of his sports-writing days in New York when he asked: "When did the Dodgers move to Los Angeles" and "When did the Giants move to San Francisco?" (Both moves were approved in 1957.) "Word spread," said McCarthy, "that this kid knew nothing about baseball. He's done. Get him outta here!"

A call from Washington

He had freelanced some articles while still in the monastery, so he began cobbling together a writing career for religious publications, including for an upstart that had come into existence in 1964 in Kansas City, Mo., called National Catholic Reporter.

One of the pieces he did for NCR on his road trip involved Martin Luther King's visit for a march in Cicero, Ill., in 1966. He did another one on Sargent Shriver, then head of the Peace Corps. It was, said McCarthy, mildly critical of Shriver.

That same year he visited the NCR headquarters. He stayed in the basement of the home of founding editor Robert Hoyt and spent a week trying to get hired, but the paper didn’t have the money for another reporter. He was actually walking out the door of NCR, intending to head back to Spring Hill to take a job as a pro on the college’s golf course, when someone said he had a phone call. It was Shriver.

"He said, 'I read this article you wrote in the National Catholic Reporter criticizing me.' I said, 'Yes, I did.' He said, 'You know, I'm sitting here surrounded by yes men. I need a no man, and you seem to be eminently qualified to be my no man. I want to meet you."

Shriver's secretary came on the phone, lined up a plane ticket to Washington and told McCarthy that Shriver wanted to interview him for a job as his speechwriter. "And that's how I got to Washington. Because of NCR — that article I wrote about him. If that hadn't happened, I don't know where I'd be — I've always loved the paper for that reason," he said. "One of those odd little quirky things. And I would end up becoming very close to Sarge Shriver. He became my closest friend outside of my family. He took me in. He was just the kindest guy." (McCarthy has written a column for NCR since 1999.)

The association got him to more than just Washington. Soon after he arrived in Washington, D.C., in 1966, he met a young woman named Mavourneen, an Irish term for "my darling." She was a 1962 graduate in nursing from Georgetown University who was working at Columbia Hospital for Women. Four weeks after meeting — and against the overwhelming advice of their families and friends — they were married.

They celebrated 50 years together in December, during which time they raised three sons and together founded The Center for Teaching Peace. The often hard-hitting columnist becomes unabashedly romantic when writing about "the woman I love infinitely." In an interview, he responds, "She's an angel," when asked how he deals with the fact that she doesn’t subscribe to all of his dietary restrictions.

Speechwriting for Shriver was just a step on the way in his career. He sent The Washington Post a number of op-ed pieces, including an appreciation of Merton, "and that got me some visibility with the Post, and so I kept sending in pieces and eventually got hired." He began writing for the Post in 1969, in the heat of the Vietnam War and continued for 28 years, through the era of the Watergate scandal and the first iterations of the war in Iraq.

He had an editor who encouraged him to write about the issues that were not normal fare for the page. McCarthy remembers his instruction: "There are two kinds of journalists, those who are problem describers and those who are solution finders. Become one of that second group."

So the young columnist went off in search of people who were engaging this matter of peace and he wrote about noted Catholics like Dorothy Day and Daniel Berrigan and expanded to the broader peace community, to people like activist David Dellinger and artists such as Joan Baez, who became a lifelong friend. Roy Bourgeois, the former Maryknoll priest who founded SOA Watch, said it was a McCarthy column on the school and its training of Latin American military officers who went on to engage in horrendous human rights abuses that got him thinking about SOA and what might be done to call attention to it.

Related: "Soldier turned philosopher specializes in military ethics, just war tradition" (Nov. 28, 2016)

And there was the occasional piece on golf and rarely a summer went by without some paean to the national pastime. In fact, he knows a lot about baseball.

No grades, no homework

McCarthy and his students from Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School, proclaiming their beliefs during class, in front of the school on East West Highway, Dec. 13 in Bethesda, Md. (Rick Reinhard)

The writer continues to write, no longer closed up in his room. The boy who stammered now does an average of 20 talks a year at colleges, high schools, elementary schools, conferences and peace groups.

During the past 23 years, he has taught thousands of young people, mostly in the Washington, D.C., area. During the first semester of this year he taught two daily classes at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School; two classes on Mondays at the University of Maryland; a Tuesday class at Georgetown University Law Center; a Wednesday class at American University; and a Thursday class at Georgetown University. In all, 169 students.

Over the years, more than 400 peacemakers have spoken in his classes — everyone from a woman from El Salvador who cleaned bathrooms at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School and became a great example for some of the students to Nobel laureates Adolfo Pérez Esquivel of Buenos Aires, Mairead Corrigan of Belfast and Muhammed Yunus from Bangladesh.

He has had his share of critics, largely private critics who admire his persistence but dismiss him as unrealistic and too unyielding in his pacifism. Some years ago, two of his high school students, arguing that he presented only one point of view, unsuccessfully sought to have his class dropped from the school’s curriculum. McCarthy welcomed the dissent and said he wished there were more thoughtful dissenters in his classes.

Last March, McCarthy spoke to a packed house at the rear of the first floor of Politics & Prose, an independent book store and coffee house in Northwest Washington, about his latest book, Teaching Peace: Students Exchange Letters with Their Teacher.

Among the crowd were parents of students who had attended McCarthy’s classes in high school or college and had their lives turned upside down. There was chatter about some of the kids becoming vegans, or taking off for a year or two of service, or changing majors or a career path because of what they encountered in his classes. They spoke of changed views about violence toward women and animals, as well as geopolitics. The career turn from writing about peace to teaching peace, it was clear, involved more than some unusual pedagogical approaches. At its deepest level, it caused students to ponder not only the literature of peace, but also to look deeply within themselves, at their own responses to the most challenging issues of the day.

He also exchanged letters with other teachers, with a death row inmate, with a 9-year-old budding writer who found out about him in a Roots and Shoots program, an initiative of environmentalist Jane Goodall.

McCarthy and students from his class at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School (Rick Reinhard)

In one exchange, he and a teacher at an exclusive high school speak of their shared opinion about grades and homework and how such things are used as control mechanisms over students.

"On the no testing, no homework and all As, [givens in his classes]," McCarthy writes, "my head is neither in the sand nor in the clouds. I'm aware that some students blow off the course and that others see it as the mother of all gut courses. Not so fast, I tell them the first day of class: this will be the most difficult course you've ever taken. You'll need to make genuine demands on yourself rather than respond to artificial demands from your teacher. Self-made people tend to be self-demanding people."

If some students struggle with the concept, so do parents. In I'd Rather Teach Peace, McCarthy recounts a phone conversation with a parent stressed out that her daughter, a student at the University of Maryland, received only a "P" in the course he taught. Pass-fail represents for McCarthy "the purest academic joy."

The parent wanted to know how her daughter did in his course. "How did your daughter do? I have no idea," said McCarthy. "You need to ask your daughter."

"But you're the teacher. How did she do?"

"Do you mean what did she learn?"

"No, what was her grade. That's what counts."

"Not in my course. What counts is what a student learns."

"So what did my daughter learn."

"How would I know? Ask your daughter. She's the only one who knows what she learned."

It didn't devolve entirely into a comedy routine. He promised the parent that if she asked her daughter what she had learned she would tell her. "How do I know? She has a honed talent for honesty — I've seen it in class — and you have a great reason to be proud of her."

'We're all compromised'

McCarthy at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School; he rides his bike to work every day except when there is ice. (Rick Reinhard)

The letters attest to the fact that McCarthy's classes have a sometimes outsized effect on students who go in expecting a quick breeze to a guaranteed A, or P. Ultimately, however, whether they do a year of service, or decide to leave ROTC in college, or otherwise take an unusual career path, many of them end up in mainstream professions — doctors, lawyers, accountants, economists — engaged in the systems and presumptions they were told to question, question, question.

"We're all compromised," McCarthy said in an interview. "You have to figure out how much you can decrease" the compromises. "I don't vote in elections. I vote every day where to spend my money and spend my time. I try to stay aware of companies and corporations that contribute to violence. I am aware of being compromised. I get a paycheck every month from The Washington Post. I was paid very well when I was writing about these issues. They take money from very violent corporations. I don't go around saying I haven't sold out. If you are aware of that and try to decrease the selling out, that's the best way to live."

With a lot of teaching along the way.

[Tom Roberts in NCR editor at large. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]

About those obscure peacemakers?

Emily Greene Balch (1867-1961), intellectual and activist, worked internationally on peace initiatives, founded the Women’s International Committee for Permanent Peace, campaigned against U.S. involvement in World War I (a pacifist view modified, on the basis of human rights concern, during World War II) and a lifelong advocate of international approaches to resources. She was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946 at the age of 79.

Jody Williams is a long-time advocate for peace, from protests against the Vietnam War to campaigning today against killer robots. She won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1997 for her work to ban land mines. According to the Web site of the Nobel Women’s Initiative, which she chairs, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines has expanded to more than 1,300 organizations in 95 countries.

Jeannette Rankin was a political activist, suffragette, pacifist and the first woman elected to Congress. She was involved in the successful campaigns for women’s right to vote in Washington State (1911) and in Montana (1914). Following her election to Congress in 1916, she formed a committee on women’s suffrage and proposed a constitutional amendment that passed the House but failed in the Senate. She spent much of the rest of her life working for pacifist causes and was re-elected to Congress in 1939, in part because of her anti-war position.