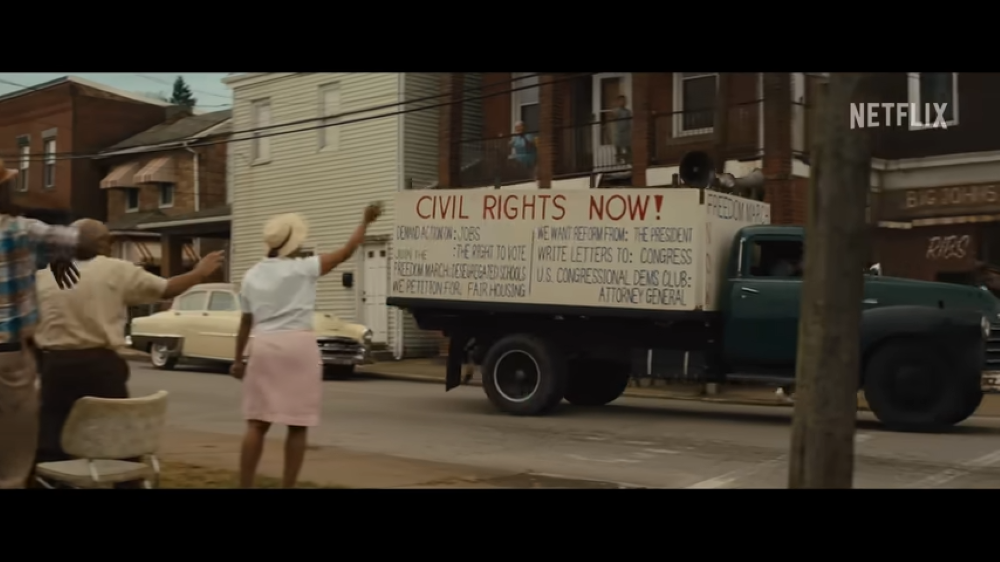

Colman Domingo portrays Bayard Rustin, the civil rights activist and chief organizer of the Aug/ 28, 1963, March on Washington. The biopic "Rustin" is streaming on Netflix. (NCR screengrab/Netflix)

Awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013 posthumously to Bayard Rustin 50 years after he served as the March on Washington's chief organizer, President Barack Obama said the honoree possessed "an unshakable optimism, nerves of steel and most importantly a faith that if the cause is just and the people are organized, nothing can stand in our way."

Given the former president's admiration for the peace and justice activist, it makes good sense that his and Michele Obama's Higher Ground Productions would executive produce the biopic on Rustin's life. Released in November to coincide with the march's 60th anniversary, "Rustin" is now streaming on Netflix. And while it is a laudable attempt to restore the appropriate historical stature of someone too many have forgotten, despite Colman Domingo's outstanding portrayal of Bayard Rustin, the biopic ultimately disappoints.

Highly regarded as a playwright and theater director, filmmaker George Wolfe ("Ma Rainey's Black Bottom") is a fitting choice to direct "Rustin." He could relate well to the activist's experience as a Black gay man. Scandalous to critics such as late South Carolina Republican Sen. Strom Thurmond and disquieting to allies such as the late peace activist A.J. Muste, Rustin's homosexuality occupied a disproportionate role in his life in a less tolerant era. The controversy unfortunately overshadowed his exceptional gifts as an organizer, and others used Rustin's sexual orientation to discredit and isolate him.

In "Rustin," Colman Domingo portrays Bayard Rustin, the activist who organized the Aug. 28, 1963, March on Washington, an event he said would "alter the trajectory of this country." (NCR screengrab/Netflix)

As the film opens, we see Rustin, working for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference , urging 31-year-old SCLC President Dr. Martin King Jr. (Aml Ameen) to organize protests at the July 1960 Democratic Party National Convention in Los Angeles. Having served three years in prison as a World War II conscientious objector and well-steeped in Gandhian nonviolence as a field organizer for Muste's Fellowship of Reconciliation, Rustin mentored the Alabama pastor in nonviolence, as the 2003 film "Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin" well documents.

Objecting to Rustin's "immoral" lifestyle and the duo's intentions to disrupt his party's convention, formidable 13-term Harlem Democratic Rep. Adam Clayton Powell (Jeffrey Wright) threatens to promote a malicious rumor about the organizers. "The world will know the truth," he says, "about Martin Luther King and his queen" Relenting to the pressure, King dismisses Rustin, naturally engendering a rift between the men, which lasted until they worked together on the march.

The filmmakers want you to believe the idea for March for Jobs and Freedom came to Rustin in an epiphanic flash. In reality, A. Philip Randolph (Glynn Turman) — head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters' Union and once regarded "the most dangerous Negro in America" — first conceived of the march in 1941. (When President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive order June 25, 1941, ending the defense industry's discriminatory hiring practices, Randolph called off the original march.)

As the filmmakers tell it, Rustin needed to persuade Randolph to join the organizing effort because he was reluctant to leave the side of his dying wife, Lucille. "We honor her by doing the work we've always done," Rustin says. While Randolph recruited the activist to organize the

march, it's also true that Rustin worked with Randolph on the 1941 march, and they began planning the 1963 march in 1961.

The British filmmaker and actor Aml Ameen portrays Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in the Netflix biopic "Rustin." King and Rustin worked together to plan the Aug. 28, 1963, March on Washington. (NCR screengrab/Netflix)

In describing the internecine squabbles among the "Big Six" civil rights leaders — King, John Lewis of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Randolph, Whitney Young of the Urban League and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP — the filmmakers stand on more solid footing.

As Wilkins, comedian Chris Rock dominates these scenes with characteristic raw anger in a memorable, revelatory turn. Representing an organization that worked through the legal system to achieve civil rights victories, he believes "mass lobbying is sheer madness." Like many in these meetings, Wilkins also maintains grievous reservations about Rustin's participation. "Every person seated at this table," the NAACP chief says, "will be in the line of fire because of him."

Randolph's decision to name Rustin his deputy mollified other leaders, with the exception of Powell. Making the most of his moments as Randolph, the venerable Turman delivers the film's most indelible line when he shuts down the politician. "Congressman Powell," he says, "we have moved on!"

The fact-based drama's significant flaws begin with the fictitious romance screenwriters Julian Breece and Dustin Lance Black invent between Rustin and married preacher Elias Taylor (Johnny Ramey). Beyond falsely suggesting that Taylor actually existed, the affair devolves into a melodramatic, irrelevant distraction when Elias' slighted wife Claudia (Adrienne Warren) threatens to expose the relationship.

Advertisement

The filmmakers should have been truer to their protagonist's own experience. They refer to Rustin's 1953 arrest for "sexual perversion" in Pasadena, California, when he was discovered in a parked car with two men. But the filmmakers failed to thoroughly explore the incident.

After the incident, the activist says in the documentary "Brother Outsider," he realized that "sex must be sublimated if I'm to live with myself in this world longer." Emphasizing how this trauma reshaped Rustin's self-perception would have made "Rustin" more authentic.

The film ultimately suffers from Wolfe's inability to create any momentum or urgency around the March on Washington, when 250,000 people gathered near the Lincoln Memorial Aug. 28, 1963, in the largest social protest in U.S. history up to that point. But the film includes no montages of participants coming by buses, trains, cars or on foot "as far as they eyes can see" to stir the imagination or uplift the spirit. We get a few snippets from King's storied "I Have a Dream" speech — and that's it. The whole thing falls flat.

The Obamas were correct. Bayard Rustin deserved a good biopic. But "Rustin" isn't it.