T.S. Eliot in his London office on Jan. 19, 1956 (AP)

How much do we need to know about the lives of writers to appreciate their work? Is the life all — or is it nothing? Should we read poetry, for example, with an eye on biography, or merely focus on the verse itself?

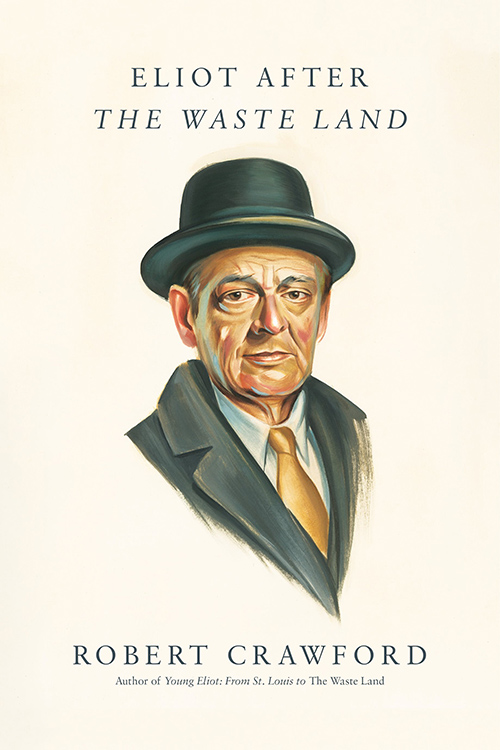

These questions hover over Eliot After The Waste Land, Robert Crawford's new biography of T.S. Eliot (1888-1965), a St. Louis native with family roots in New England who settled in London and became one of the last century's greatest poets and literary critics.

Though Eliot's work does not command the same attention it did in mid-century — Eliot won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1948, nearly 75 years ago — an Eliot revival may be underway, especially now.

The year 2022 marked the 100th anniversary of the publication of Eliot's "The Waste Land." The poem's centenary is renewing attention on one of the landmarks of 20th century modernism: a work that has challenged, infuriated and delighted readers since its initial publication. A multivoiced, demanding and densely textured work of collage, "The Waste Land" remains an unsettling and thrilling read a century later.

It is a work that can be read as reflecting a fractured Europe awakening from the cultural calamities of World War I; a poem that distills the era's sorrows and horrors, beginning with one of the most famous openings in all of English-language poetry: "April is the cruellest month ..."

With its depiction of haunted, damaged and brutalized landscapes, "The Waste Land" is now being studied and embraced by scholars concerned with "eco-criticism" who suggest the poem may have something to say to us about our climate crisis.

Advertisement

Aside from new scholarly studies of "The Waste Land," other sources of a possible Eliot revival are several biographies — Crawford's being the most prominent — that include new information about the poet. Of particular interest are excerpts from 1,131 letters unsealed in 2020 that chronicle Eliot's decadeslong chaste, epistolary romance with Emily Hale, an American whom Eliot first knew when he was a graduate student at Harvard.

When Eliot's letters to Hale, deposited by Hale at Princeton University, were finally open to scholars, the Eliot estate released a prepared statement from the poet, dead for 55 years. As if speaking from beyond the grave — Eliot knew the letters would eventually be made public — the poet belittled Hale, uncharitably denying he had ever loved her.

Complicating the story is that Eliot, at age 68, married his 30-year-old secretary, Valerie Fletcher, in 1957. It was his second marriage, and, as Crawford notes, a happy one. His first, by all accounts, was a mismatch and nightmare both for Eliot and his wife Vivienne.

Eliot later acknowledged that theirs was an unhappy union, but said that it "brought the state of mind out of which came 'The Waste Land.' " (Asked to recite the poem in public readings throughout his life, Eliot seemed to tire of "The Waste Land," eventually calling it "just a piece of rhythmical grumbling.")

Crawford's meticulous and detailed (sometimes exhaustingly so) 624-page biography covers this all — proving to be a worthy companion and coda to Crawford's first volume examining Eliot's early years.

The biography focuses on the life. But it affirms the importance and primacy of the verse — why, after all, would we read a biography of T.S. Eliot? — and in ways that make you go back to the poetry. This happened to me after reading Crawford's chronicling the "Journey of the Magi," a 1927 poem written in the wake of Eliot's conversion to Anglo-Catholicism.

Unlike "The Waste Land," "Magi" is an accessible poem, often read and recited during the Christmas season. Written in the voice of one of the three wise men, the poem explores both new life — the life of Christ — and its connection to death.

While the speaker says he had seen "birth and death" and thought they were distinct, "this Birth was / Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death." With this, Eliot movingly expresses some of the ineffable mysteries of Christian faith.

Crawford's concise analysis rightly places the "Magi" poem in the context of Eliot's embrace of Christianity. Eliot had been raised as a Midwestern Unitarian — not a typical prelude for a British subject who later described himself as a "classicist in literature, royalist in politics, and Anglo-Catholic in religion." (Eliot's conversion startled and puzzled friends and fellow modernists like Virginia Woolf and Ezra Pound.)

While the young poet who wrote "The Waste Land" was attracted to Buddhism, Crawford notes, "Magi" was a Christian work, affirming Eliot's newfound religious commitment. "Where once he might have sought to conceive death and rebirth in Buddhist terms," Crawford writes, "now his focus was intensely Christian."

Crawford adds elsewhere that "increasingly, afflicted by his sense of the 'waste' and 'hollow,' he [Eliot] turned towards the suffering Christian God."

Even so, Eliot's life was often disquieting. Crawford does not underplay Eliot's least attractive qualities. These include his chilly elitism — which often comes off as the performative act of a shy, vulnerable and insecure man — and, more damningly, Eliot's troubling antisemitism, which was not limited to a few youthful early poems. (At one point Eliot complained of his frayed relationship with "Jew publishers.")

Such failings, Crawford's biography and, in particular, the Hale letters animated an annual weeklong conference in July at the University of London I attended in which scholars, authors, poets and poetry lovers gathered to consider Eliot and his legacy.

At one point during this event, I overheard two young scholars speak of Eliot, saying they loved the poetry but lamented that he had not been a better person. ("I wish he hadn't been such an [expletive]," said one.)

In a similar vein, I asked Crawford, who lectured at the event, if Eliot had been good company during the biographer's years of extensive research. He told me that it was not always an easy experience but that his job as biographer was not to judge his subject but to write a fair, nuanced work.

In comments included in a recent online discussion of "The Waste Land" on the Literary Hub website, Crawford continued that spirit of critical fairness. In the forum, headlined "The Most Important Poem of the 20th Century," Crawford noted that, over the decades, "The Waste Land'' has held an "uncanny grip ... felt by more and more people across a range of cultures, classes, races, genders on every continent."

"Eliot may have been an intellectual elitist, a self-confessed snob, and at times a cutting and cruel man with antisemitic and racist streaks who could exploit women; but (as well as being, e.g., a brilliant publisher, critic, children's writer, successful dramatist, public intellectual, and poet) he was also a human being who registered deep hurt, love, longing and spiritual hunger," Crawford argued.

"In other words, like it or not, he was like most of us. What made him exceptional was the way he could so memorably articulate what are common human experiences, and give them a new, sharper figuration in words that go on ringing and are unlikely to fall silent."

Eliot's singular life will always prompt new biographical study — which Crawford pulls off brilliantly. But as Crawford would be the first to say, in the end it is the poetry that commands our deepest attention.

[Chris Herlinger, the international correspondent for NCR's Global Sisters Report, holds a master's degree in creative writing from the University of Edinburgh and is a published poet, most recently at the Collegeville Institute's Bearings Online.]