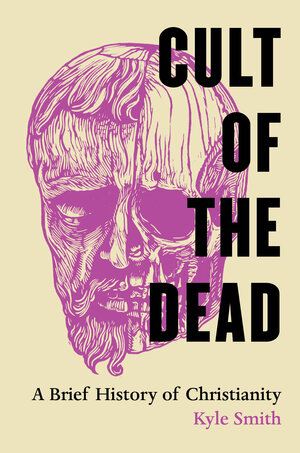

Sculpture of the bandaged, severed head of St. John the Baptist in the Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, Baths of Diocletian, Rome (Unsplash/Peter Chiykowsk)

Every Halloween, there are Catholic schools that allow their students to dress in costume on the condition that the costumes must be Catholic saints. While this policy might be intended to eliminate costumes featuring excessive gore or threatening weapons, a creative student of the stories of the saints could still put together a hair-raising ensemble. Using only a piece of cardboard, a tablecloth and a paper plate with the center cut out, I myself once went out on Halloween as St. John the Baptist — or, at least, as his head.

The stories of the martyrs are fertile ground for costume and prop designers. Imagine, for instance, a little girl dressed as St. Lucy, complete with her two eyeballs rolling around on a plate; or a child with a wheel strapped to her back in imitation of St. Catherine of Alexandria. Making use of just a few surplus pencils, a Catholic school teacher like myself might arrive on Oct. 31 dressed as St. Cassian of Imola, whose unappreciative students stabbed him to death with their sharpened styluses after their schoolmaster was outed as a Christian.

Christians, and Catholics in particular, have always had a fascination with the stories of their glorious dead. The names, dates and remains of our honored dead have come to have a rich and lasting cultural impact that permeates far below whatever depth at which the bodies of these holy women and men might be buried. In the first two sentences of the introduction to Cult of the Dead, Kyle Smith explains how this seemingly macabre preoccupation actually cuts right to the heart of Christianity and the Gospels.

"Christianity," Smith begins, "is a cult of the dead. And the story of its obsession with martyrdom and the remains of the dead go back to the cross." For the Christian, the death of every martyr, from St. Stephen's stoning to the present day, is an imitation of Jesus' on the hill of Golgotha.

'Historically speaking, it’s not the sun-wrinkled smile on Mother Teresa that is the icon of Christian holiness — it's the char-grilled one on Lawrence.'

—Kyle Smith

Smith notes how the martyrs' faces are traditionally illustrated as pictures of stoic resignation and serenity. Some are even smiling. The most beloved martyrs are not just those who die brutal deaths, but those who can endure burning and dismemberment while maintaining a sense of humor.

Chief among such stories is one I first heard from my mother as a young boy: the martyrdom of St. Lawrence. After introducing the indigent population of Rome to an enraged imperial enforcer as "the treasure of the Church," Lawrence meets his death on a grill, departing the earth after wryly suggesting that it was time for the grill master to flip him over. Smith holds up Lawrence as a prototype for Christian martyrs, and saints in general. "Historically speaking," he writes, "it’s not the sun-wrinkled smile on Mother Teresa that is the icon of Christian holiness — it's the char-grilled one on Lawrence."

"The Martyrdom of St. Catherine of Alexandria" by Italian artist Bernardino Poccetti (1548-1612) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Smith shows that just as our fascination with the martyrs is rooted in the cross, our fascination with their relics is rooted in Christ's incarnation. He writes, "For King Louis [of France] and every other ancient and medieval Christian, Christianity's materiality was faith." Catholics who believe in the doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist already feel this implicitly.

Smith illustrates his point by comparing relic hunters like the Emperor Constantine's mother Helena with the children who "clawed at the mound," "dug for home plate," and "scooped dirt into empty paper bags" after the last Dodgers home game at Ebbets Field. After all, this was the hallowed ground upon which the likes of Jackie Robinson and others "stood and spit and sweated." Smith continues, "Jesus too once stood and spit and sweated."

But authentic saints' relics were historically hard to come by. Sometimes, even their names were hard to find.

Advertisement

Kyle Smith tells us the fifth century church historian Sozomen discovered this while trying to collect the stories of an estimated 16,000 Christians martyred in far off Persia. Increasingly frustrated, Sozomen reckoned the vast majority of them "beyond enumeration." Enamored with solving an academic mystery, Smith's prose conjures up images of manuscript-strewn floors in ancient libraries and crumbling stacks finally giving up their secrets. In the early 2000s, a document was discovered in an Egyptian monastery that would have helped Sozomen complete his list. Even then, many of the Persian martyrs remained anonymous. One is described only as a monk with a pierced ear.

Cult of the Dead is the rare academic book that shows empathy; for the martyrs themselves, tor those with devotion to them, and even for disgruntled historians like Sozomen. Smith also shows empathy for the reader, knowing that "specific stories about specific martyrs would always move people in ways that an abstract account of the dead (no matter how overwhelming a number) simply could not."

In Cult of the Dead, Smith does our dearly departed the ultimate favor: He allows the dead to speak once more.