This is a scene from "Into Great Silence," a documentary by filmmaker Philip Groning about monks at a Carthusian monastery in the French Alps. (CNS/courtesy of Zeitgeist Films)

Reading a book is a solitary act. Watching a movie may be as well. But combining them, as Kathleen Norris and Gareth Higgins do in A Whole Life in Twelve Movies: A Cinematic Journey to a Deeper Spirituality (foreword by Jesuit Fr. James Martin), can seed fruitful conversation and fulfill the human need for "art that's steeped in the mystery of life, offering hope without denying real human suffering."

Both authors are spiritual seekers of long-standing distinction. In addition to The Cloister Walk, in which she wrote about her year as a Benedictine oblate in a Minnesota abbey, Norris has probed the overlap of spirituality and daily struggles in poetry, essays and memoir. Higgins, born in Northern Ireland, is a peace activist and storyteller, the driving force of The Porch, a prolific author, founder of Wild Goose Festival and a movie buff. They make a good, if initially surprising, pair.

Chapter by chapter, the authors reflect on 12 phases of the human journey from womb to tomb, in the context of a carefully chosen movie. Trusting each movie to resonate as a unique, visceral experience, the authors take turns examining the impact of each movie. The essays are not formulaic, but fresh — with personal insights and experience, social, historical and artistic considerations, their individual interpretation of the movie and spiritual grasp of the theme.

The authors do not always agree; nor would readers automatically nod in agreement with either point of view. The shared goal is to open up to new possibilities and admit the messy ambiguity demanded by life itself. The authors also provide probing questions at the end of each chapter and suggestions for further movie viewing. The book stands alone, with the authors' summaries and reflections and whatever cinematic memories we can summon as readers. But when paired with actually watching the suggested movies, the book rises to a new level altogether: an experience, no longer a book.

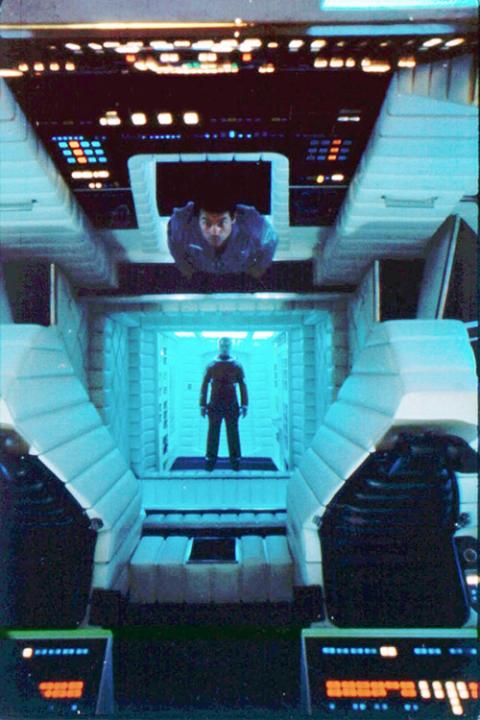

Some movies are familiar, such as "2001: A Space Odyssey," "Malcolm X" and "Wonder Woman." Others it was time I revisit, like "The Fisher King" and "Babette's Feast." A few, like "Paterson" and "Faces, Places" had previously escaped my notice altogether.

If it weren't for the companionship provided by the book, I might have stopped watching the galling and painful "What Maisie Knew," which provided the springboard for the "Childhood" chapter, or "After Life," the Japanese film probing liminal possibilities in the "Death and Beyond" chapter.

At one point, Higgins asks: "Do I truly recognize that your life has the same value to you as mine does to me?" The scenes chosen for dissection frame that inquiry well.

Advertisement

In "Smoke Signals," the first movie entirely produced by Native Americans, a radio announcer intones a daily traffic report on Idaho's Cœur d'Alene Reservation. There is none, other than an occasional big truck sighting. The first time this happened, I belatedly laughed; after that, I waited for it. How better to evoke the film's themes of community, than such humor in the midst of isolation?

When the family dog destroys Paterson's notebooks in the so-named movie, I experienced the anger, frustration, self-blame, self-doubt, sadness, self-pity, mixed with indomitable drive, that is familiar to anyone trying to hone their unique voice into a suitable "Vocation." The second chapter devoted to the Vocation theme centers on the must-watch movie, "Malcolm X." To walk in his shoes, even for a bit, is to re-experience the '60s, with all its dead ends and devastation; the brutal murder of our heroes and our best aspirations.

This is a scene from Stanley Kubrick's ''2001: A Space Odyssey."(OSV News file photo)

How sad (and infuriating) is one of the films chosen for the "Relationships" chapter, "Love Is Strange." The film opens with a joyful wedding ceremony, only to have the newlyweds' lives immediately break apart. They lose their home because the breadwinner loses his job in the church as a direct reaction to the public witness of their commitment. They have to reckon with an eroding family network, and in the end, they lose their entire relationship to a catastrophic health event. Did I mention this was a gay couple who had been in a loving relationship many years prior? Their dignity in the face of this Job-like spiral haunts me, as well as the Catholic Church distilling and intensifying the general social homophobia.

One clear takeaway from the book is that a movie need not be overtly spiritual to be profoundly spiritual. The final chapter deals with what lies beyond, and it is appropriately paired with the only distinctly sacred movie. "Into Great Silence" is a nearly three-hour documentary of life in the cloistered Grand Chartreuse monastery of the Carthusian Order in France, remarkable for its lack of lighting and long periods of cinematic silence, punctuated by feet shuffling down quiet halls and spoons clinking empty bowls. The movie offers entry into an unworldly world, but I was most taken by a brief scene depicting the monks breaking their silence to converse while out for a snowy walk on their day of rest.

As Norris and Higgins understand, the urge to communicate — even among hermits, even in a quiet movie house as we struggle to suppress our whispers — is the most human urge of all.