Patricia Fresen, right, greets Elsie Hainz McGrath during a ceremony at which Fresen ordained McGrath and another woman at the Central Reform Congregation Synagogue in St. Louis in this Nov. 11, 2007, file photo. Women Called to Catholic Priesthood shares stories of women who followed their call to priesthood through ordination. (CNS photo/Karen Elshout)

Back in 2001, when Pope John Paul II's moratorium on the discussion of women's ordination had most Catholic institutions cowering, I was working for U.S. Catholic magazine, a lay-led publication founded during the Second Vatican Council by the Claretian order of priests and brothers.

Rather than risk publishing articles arguing about church teaching, we editors instead decided to profile five women who felt called to priesthood and let them tell their stories. The women were young and old; African American, white and Latina, and they responded to their vocational calls in different ways. One was ordained in a Protestant denomination; one has since gone to God and I believe at least one has now left the church.

Their stories of sensing a call from God from a young age, of struggling with the pain and frustration of a church that prevents them from answering that call, and their decisions about what to do with that call were compelling. I'm so glad we provided the space for them to be told.

None of their stories, however, included pursuing ordination through what's now known as Roman Catholic Womenpriests. That movement began a year after our article's publication, in 2002, when seven women from Germany, Austria and the United States were ordained on a boat on the Danube River (where there was no ecclesial jurisdiction) by a bishop the group claims had apostolic succession.

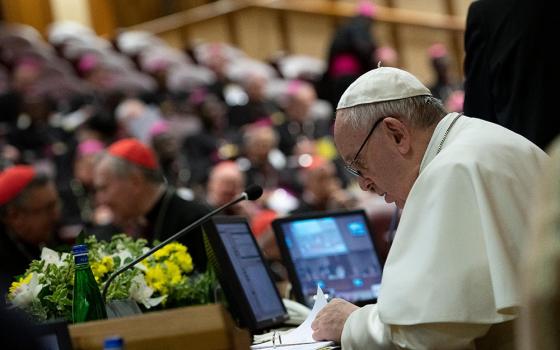

Now the church can hear the stories of women who have chosen to follow their call to the priesthood through ordination, thanks to a new book by Sharon Henderson Callahan and Jeanette Rodriguez, Women Called to Catholic Priesthood: From Ecclesial Challenge to Spiritual Renewal (Fortress Press, 2024). Callahan and Rodriguez are both affiliated with Seattle University, the former as professor emerita and the latter as a professor and director of the university's Institute for Catholic Thought and Culture.

Callahan and Rodriguez tell the stories of 42 women in the United States, Canada, Colombia, Europe and South Africa who chose to challenge Canon 1024 with ordinations that are considered illicit by the institutional church and carry the penalty of excommunication. The authors not only trace the womenpriests' vocation stories, but examine the spiritual practices and theological beliefs that undergird their decisions and sustain the women throughout their ministry and challenges from the institutional church.

Ida Raming, one of seven women ordained to the Catholic priesthood on the Danube River in 2002, speaks to reporters on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, in this July 22, 2005, file photo. Diane Watts, national president of Women for Life, Faith and Family, holds a protest sign in the background. Raming was excommunicated following her ordination. (CNS/Art Babych)

The authors describe the women's journeys collectively, drawing conclusions about them as a whole, but also quoting them individually. The women are identified by first name only, although the appendix includes a list with the full names of the women interviewed.

All felt stirrings of a call early in life and tried to respond within the confines of the church by pursuing other forms of service, including vowed religious life, parish lay ministry, social justice work, health care, chaplaincy or education. Half married and had children and grandchildren. Most waited until they retired from other professions to be ordained, since few are able to financially support themselves as priests. Not only is compensation minimal or nonexistent, but the women must finance their own education.

"Like St. Augustine, each admitted that their hearts were restless as they searched for the best way to answer the God that called them," the authors write. "Each grappled with closed doors, ostracization from friends, parishioners and family, and the threatened expulsion from the religion they practiced and loved. Like Jeremiah, each at times cried out in pain wondering how God could call them to ordained priesthood, when everything in their religion's rules rejected that call."

(Unsplash/Kelly Sikkema)

The book puts the women's experiences in the context of the Second Vatican Council, as well as the more recent rightward shift in the church. The authors also weave in and cite other scholars' applicable work. I found particularly insightful feminist scholars Alice Eagly and Linda Carli's three phases and barriers to women's vocations: the concrete wall, the glass ceiling and the labyrinth.

The concrete wall feels impenetrable, like the patriarchal structure of the church and the excommunications that now define their relationship to the church. The womenpriests see themselves breaking through the stained glass ceiling, much like their Protestant and Jewish counterparts. The labyrinth symbolizes the circuitous path women must take to positions of authority.

"We found this metaphor helpful in describing the twists and turns of each womanpriest's journey toward ordination," the authors write. "As we moved into the process of listening to their stories, we heard their pain and their joy: the obstacle that causes a turn and an opening they can move forward through."

For example, one woman, Jane, earned a doctorate in Scripture and was a tenure-track faculty member at a Catholic university. After signing a petition in The New York Times opposing church teaching on contraception, the local bishop blocked her tenure application. She went on to earn a law degree and became the prosecuting attorney for the city of San Diego. Throughout it all, she felt called to ordination.

Advertisement

Some women described support from priests, even bishops, though often secretly. Some still attend Catholic parishes and even receive Communion there. But too often, representatives of the institutional church were hurtful. Some womenpriests were shunned not only by church leaders but by their former fellow parishioners. One priest, who had befriended two womenpriests who were a couple, asked the one who was dying to "repent of her priesthood" before giving last rites.

"The most common path for all women attempting to enter ground previously closed has been simply to do the work," the authors conclude. "As countless authors have noted, women have entered into most professions by showing up, working hard, and staying the course."

History will tell if these women are merely "ecclesial challenge" or a "spiritual renewal." But the church should be grateful that Callahan and Rodriguez have documented their historic stories. If anything, this book left me wanting more women's stories. Let's keep telling them.