A woman holds a crucifix in this 2010 file photo. John Van Hagen's book Promise and Poison focuses attention on the traumatic impact of the Crucifixion on the first disciples and their followers, as well as the devastating effects of the destruction of the Temple a few decades later. (CNS/Reuters/Vasily Fedosenko)

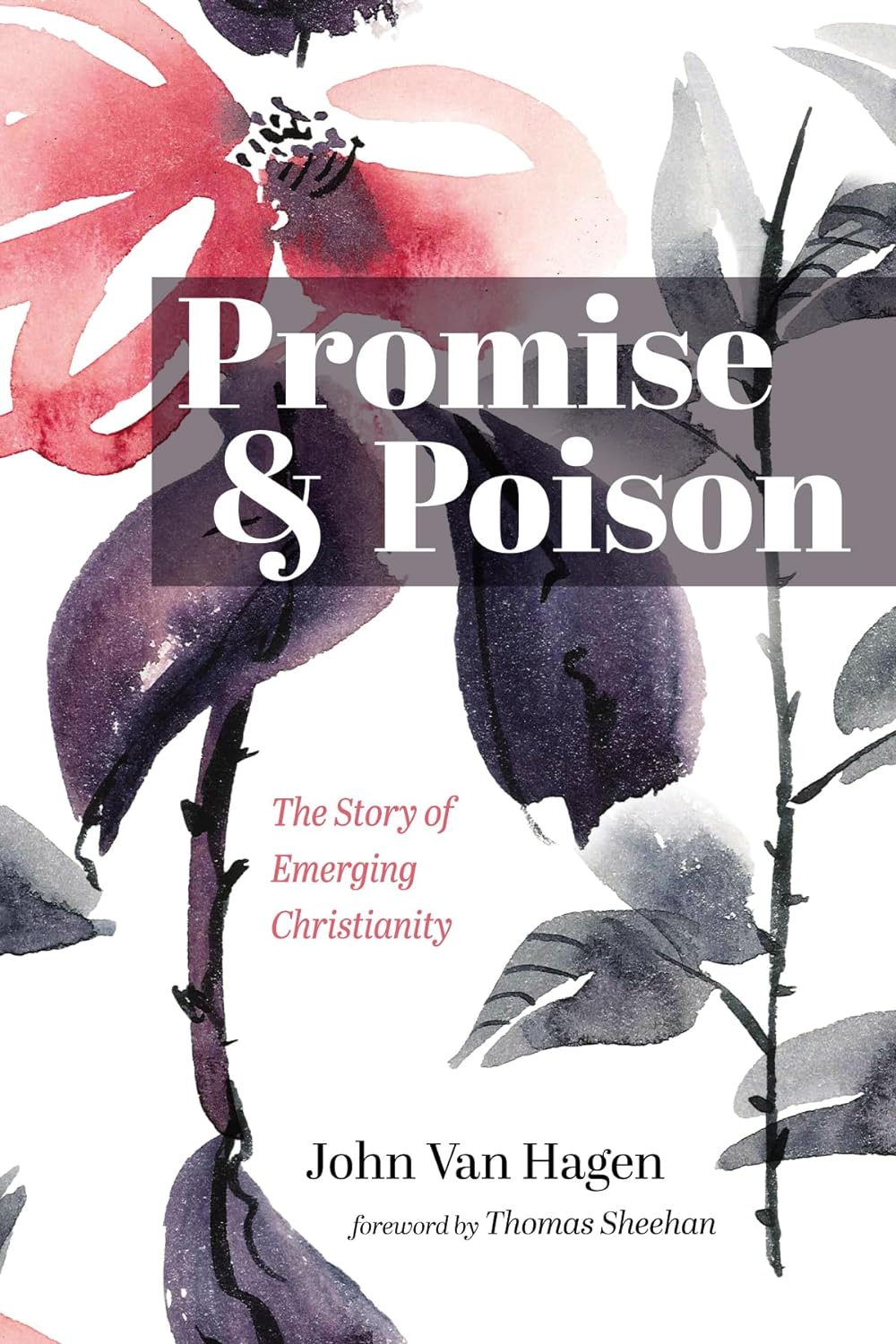

In the last chapter of his book Promise and Poison: The Story of Emerging Christianity, John Van Hagen writes:

My purpose in writing this book is to present the efforts of emerging Christianity to create moral communities as a model or case example of the immense difficulties and potential solutions in forming such idealistic groups. … They had to articulate who Jesus was and just why he was so cruelly executed. They had to decide about membership requirements. … They experimented with forms of leadership and faced the conflict and uncertainty endemic to the beginnings of any idealistic movement.

Relying on contemporary interpretations of New Testament authors, Van Hagen emphasizes the importance of understanding the "agendas" of the various writers and their editors. To that end, I should disclose that John Van Hagen and I are members of the same seminary class. Ordained shortly after Vatican II, we were close as priest friends and became even closer over the years as we each got married and raised children.

As Van Hagen is a trained psychologist, Promise and Poison focuses a lot of attention on the traumatic impact of the Crucifixion on the first disciples and their followers, as well as the devastating effects of the destruction of the Temple a few decades later.

Van Hagen reminds us that the very first Christians were Jewish believers, many of whom continued to attend the synagogue. He also reminds us that both the Crucifixion and the destruction of the Temple contradicted, in the minds of the first disciples, their expectation that the "endtime" was at hand — and that this unrealized hope and its cognitive dissonance influence the way the narratives created by the early Christian communities unfolded.

The title Promise and Poison refers to the ways in which the attempts of the early Christians to establish their identity "inspired altruistic behavior and nourished the hope that others would join their community. Others interpreted the crucifixion as a call to right thinking and a mandate to persecute those who believed differently."

The first few chapters of the book explore many of the New Testament writings, beginning with some of Paul’s earliest letters and followed by the Gospels of Mark, Matthew and John. Van Hagen aligns himself with scholars who date Luke’s Gospel and Acts as late as 100 C.E. I will leave it to Scripture scholars to evaluate Van Hagen’s choice of exegetical understandings of the stories of "Emerging Christianity" that are captured in the New Testament.

"Plaque with Saint Paul and His Disciples," a circa 1160-80 British plaque; according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the inscription "refers to the epistles Paul addressed to the various early Christian communities (Romans, Corinthians, Philippians) among whom he traveled." (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Readers not familiar with the progress made by archaeologists, historians and Scripture scholars in understanding the writings of the New Testament might be surprised by some of Van Hagen's accounts of how the earliest Christian communities emerged with significant differences in the way they appropriated the meaning of the Crucifixion and how they dealt with the growing number of Gentiles who became followers of Jesus. His descriptions are, for the most part, quite consistent with Raymond Brown's wonderful book The Churches the Apostles Left Behind.

Van Hagen effectively shows how, in their need to find an identity, the early Christians created boundaries that demonized those on the outside (especially Jews and some well-meaning "heretics") while also creating an unhealthy dependency (sometimes evidenced as a lack of critical thinking) and harmful internal divisions.

While Van Hagen regularly attends a Sunday Roman Catholic Eucharist, he has also described himself as an agnostic (see his previous book, Agnostic at the Altar). This may be why he doesn't give much attention to the belief in the Resurrection as an important part of the way early Christians made sense of the Crucifixion. Nor does he unpack the way the early Christians relied on their belief in the Holy Spirit to help them in their faith journey. And I wish he had given more attention to the way the celebration of the Eucharist illustrated the unity of early church communities despite their many differences.

Advertisement

The last four chapters of the book focus on the history of the emerging Christian communities in the mid-second century. Van Hagen is quite taken with the Christian community described in the Didache. The structure of this community appears to be quite different from the church in Antioch and the role of its bishop, Ignatius, who exercised his authority in promoting the almost unconditional power of bishops — an issue still with us today that stands in stark contrast to a "synodal" church.

After reading this book, I was left with three main takeaways. First, storytelling is a powerful dynamic that contributes to the emergence of communities — and to understand the story, one must understand the agenda of the storyteller. This applies not only to the New Testament writers but also to the institutional church, which, over the centuries, has ignored emerging Christianity conflicts and presented instead a neatly packaged, airbrushed narrative of Catholic teaching.

My second takeaway is that the first followers of Jesus created diverse small communities whose identity was marked more by their moral choices and the celebration of the Eucharist than by an adherence to a set of dogmatic beliefs.

And finally, I noted that in creating boundaries as part of their search for identity, communities need to be careful about how they perceive those on the "outside" and what they demand of those on the "inside." Equally, we need to have a good dose of humility in formulating truth claims that might define our identity as believers.