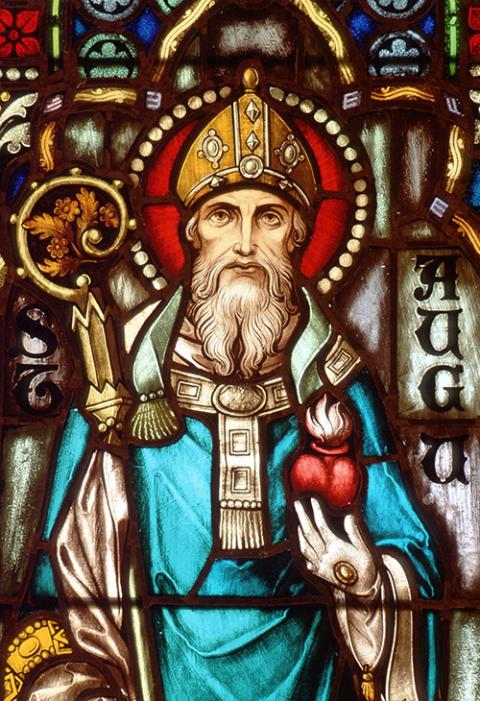

"Saint Augustine" (circa 1645), by Philippe de Champaigne (Artvee)

For years, I couldn't shake the notion that St. Augustine was boring. Despite his profound influence on 1,600 years of theologians, ethicists and church leaders who've molded the Christian tradition, I couldn't help but drift toward medieval mysticism or the spiritual guidance of 20th century luminaries such as Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton. I routinely averted my gaze from course offerings in early Christianity, dismissing Augustine’s Confessions altogether whenever it came across my eye on the library shelves.

But Kathleen Bonnette took me on a theological journey, shedding light on how Augustine's timeless questions continue to resonate and evolve in our modern era. Her book, (R)evolutionary Hope: A Spirituality of Encounter and Engagement in an Evolving World, weaves scholarly insights on this saint together with personal anecdotes that reflect her own evolving identity as a Catholic within the complex political landscape of the contemporary Catholic Church in the United States.

At the core of her book lies a vital narrative. Bonnette, an adult convert to Catholicism, shares her life as a theological scholar captivated by the rich intellectual tradition of the church. Simultaneously, she details her process of unlearning ingrained prejudices and attitudes around issues of race, gender, sexuality and — fundamental to all of these topics — structures of power. Shedding the hierarchical trappings that shape power within the church, Bonnette writes:

While it was Augustine's influence that first drew me to the Catholic Church, my engagement with women religious in the work for peace and justice drew me more deeply into Catholic faith. … They expressed spiritual sensibilities that emphasized encounter and inclusion: their love was ordered, in practice, toward relationship before dogma. Through them, I learned to define Catholicism in terms of wholeness and interconnection, rather than hierarchy.

I loved this book for its pursuit of ecclesial wholeness. Bonnette defies our inclination to view the church as "a power struggle" where " 'our side' wins — for the good of the church" and opts instead "to reflect Christ's heart — a heart that is always open to encounter." In today's polarized political climate, this approach is more crucial than ever. Through the lens of Augustine, she masterfully delves into the potential of a Catholic imagination that challenges divisiveness. This provides a fresh perspective on spirituality and active engagement in our ever-evolving world.

While Bonnette does share from her own life as she examines Augustine's theological reflection and dialogues with contemporary figures, I found I desired a more comprehensive exploration of Bonnette's personal narrative. Everyday examples of balancing work and family life, for instance, come and go with brief detail. The book predominantly leans toward theological discussions on Augustine's cosmology and reflections on original sin. Nevertheless, it's evident that the book aims to deeply resonate within readers' personal reflections through guided questions and the stories we do glean from Bonnette's life.

Take, for example, an anecdote she shares from her doctoral studies. After delivering a lecture on love and justice in Augustine's theology, Bonnette advised a young woman who was both a Catholic campus minister and a lesbian. Bonnette stressed to her that the church's institutional teachings labeling LGBTQ+ love as "intrinsically disordered" were essential eternal truths for personal flourishing. Bonnette recounts the young woman's response:

Her eyes, resigned, held the hurt of a wound torn open yet again, as she graciously but pointedly asked, "Shouldn't our human experience have something to offer orthodoxy?"

To share this painful moment with us is a gift. We learn that this young woman's question became a significant part of Bonnette's theological and spiritual journey. By sharing this moment with her readers, she reignited my own journey as a reader and a queer Catholic who, in my own theological studies and personal wounds, could have found myself in a similar situation to that young woman. It reminded me of the times when my experiences of love, including God's love, were marginalized in the name of orthodoxy and truth by peers, professors and guest speakers.

Advertisement

By this token, Bonnette's acknowledgment of "Augustine's intellectual paradigm contributing to much violence," along with her compelling reasons to counter that violence through his own words, alleviated my apprehension about delving into his theology through her lens. Where I once worried that Augustinian theology might be used to challenge my Catholic experiences and faith, I discovered in Bonnette a guide who encouraged me to explore his theology with curiosity, safety and in the spirit of her own personal quest for knowledge.

Kathleen Bonnette shows how tradition can engage in meaningful dialogue with justice. When you delve into this book, especially if you've overlooked Augustine in the past, don't expect to walk out with a comprehensive understanding of his theology. You will certainly gain a deeper understanding. But even more so, aspire to navigate her chapters by embracing the theological richness of your own human experiences, imperfections included, while contemplating God's creativity.

*This story has been updated to correct the spelling of author Kathleen Bonnette's name.