Some 50,000 members of the National Legion of Decency, including parochial school students, parade down Michigan Avenue in Chicago on Sept. 27, 1934, to demand "decent movies." (Shutterstock/Everett Collection)

In May 1934, Cardinal Dennis Dougherty of Philadelphia issued a public rebuke of Hollywood, calling on the city's 800,000 Catholics to boycott motion picture theaters, which he regarded as "perhaps the greatest menace to faith and morals in America today." In a letter sent to every parish in the archdiocese, Dougherty made it clear that this was "not merely a counsel but a positive command, binding all in conscience under the pain of sin."

The results were devastating to the industry: Approximately 300,000 Catholics signed a pledge agreeing that it was sinful to enter a movie theater. Ticket sales dropped by 20%. Democratic Committee Chairman John Kelly (father of actress Grace Kelly) protested and Hollywood studio heads begged Dougherty to end the boycott, to no avail.

A decade prior, studios in Hollywood had formed the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America with the intent of rehabilitating the film industry in the wake of risqué films and growing celebrity scandals. Will Hays served as the first president, and while studios were not required to send scripts to Hays' office, studio heads were still wary of adhering to a code that could potentially invite government censorship.

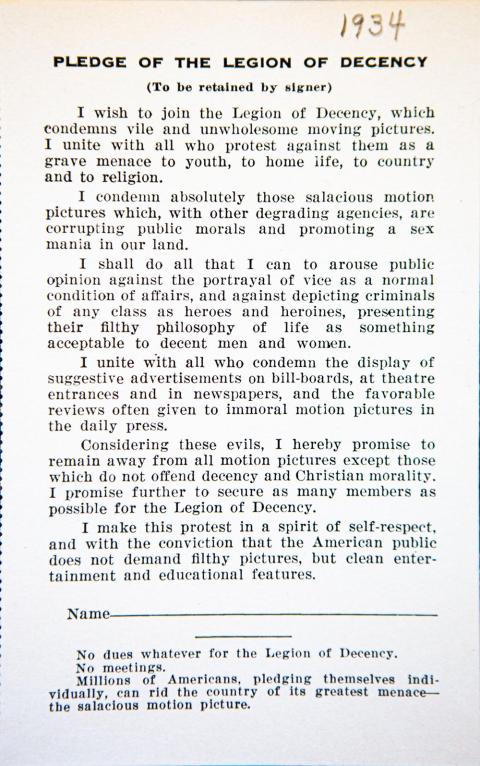

But the Philadelphia boycott was a strong enough spark to create the National Legion of Decency, founded in 1934 by the archbishop of Cincinnati. The purpose was to identify objectionable content on behalf of U.S. Catholic moviegoers, some 20 million strong at the time. Every year, Catholics were required to take "the Pledge," condemning indecent films.

The Legion consisted of a panel of religious censors who had the power to control Hollywood (which had thus far failed to regulate itself) through its scripts, story lines and subject matter. Married couples could not sleep in the same bed. Once, a shot of a woman spraying perfume behind her ears was deleted.

The Pledge was also antisemitic, aimed at hurting the Jewish major studio heads.

"The heart of the issue was money," Gregory Black, a retired communications professor and author of The Catholic Crusade Against the Movies, 1940-1975, told NCR in an interview. "The Legion said to Hollywood, 'If you let us control the content, we'll let Catholics go to the movies.' The studios said to themselves, 'That's a guaranteed audience.' "

The Legion graded films, either A (morally permissible), B (objectionable in part) or C (morally unacceptable). "The Legion could take out anything they found objectionable," Black added. Hundreds of scripts were passed around and edited, with dialogue removed and scenes cut. "It was a mess."

Dougherty never receded his declaration. He did, however, eventually have a private screening room installed in his Philadelphia home.

These days, Hollywood is finding the Catholic church to be a font of source material, even aside from the redundant nunsploitation horror movies. (The latest of which is "Immaculate," a nightmarish story starring Sydney Sweeney as a young nun in an Italian convent who becomes pregnant without sex and then strangles a cardinal with her rosary beads.)

Advertisement

"Conclave," the fictional story of a cardinal tasked with leading the selection of a new pope, garnered rave reviews. Academy Award winning actor Cillian Murphy's new release, "Small Things Like These," about a man who discovers disturbing secrets kept by the local convent, was nominated for Best Film of 2024 at the Berlin International Film Festival.

Streaming now on Prime Video and Apple+ is "Cabrini," the biopic of Frances Xavier Cabrini, the Italian nun who arrived in New York City in 1889 and founded the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in response to overwhelming poverty and crime. She was canonized in 1946.

Next up? Martin Scorsese is prepping an 80-minute film about Jesus based on the 1973 novel A Life of Jesus by Shusaku Endo (author of Silence). The famed Catholic director waded into similar waters in 1988 with "The Last Temptation of Christ," which was banned in some countries and prompted fundamentalist Catholics to torch several cinemas in France. Due to death threats against him from religious groups, Scorsese was accompanied by bodyguards during public appearances surrounding the film's release.

Scorsese's adaptation of A Life of Jesus will explore the teachings of Jesus without proselytizing, according to a Jan. 8 article in Variety. Scorsese, who is financing the project independently, said he was "trying to take away the negative onus of what has been associated with organized religion. You may reject it. But it might make a difference in how you live your life — even in rejecting it."

During Dougherty's era, plenty of Catholics rejected the Pledge. For many, the idea of attending "condemned movies" was irresistible. (I can relate: I remember standing in front of a theater in Atlantic City when I was 14 and deciding — despite the certainty that I would burn in hell — to buy a ticket to "Rosemary's Baby.")

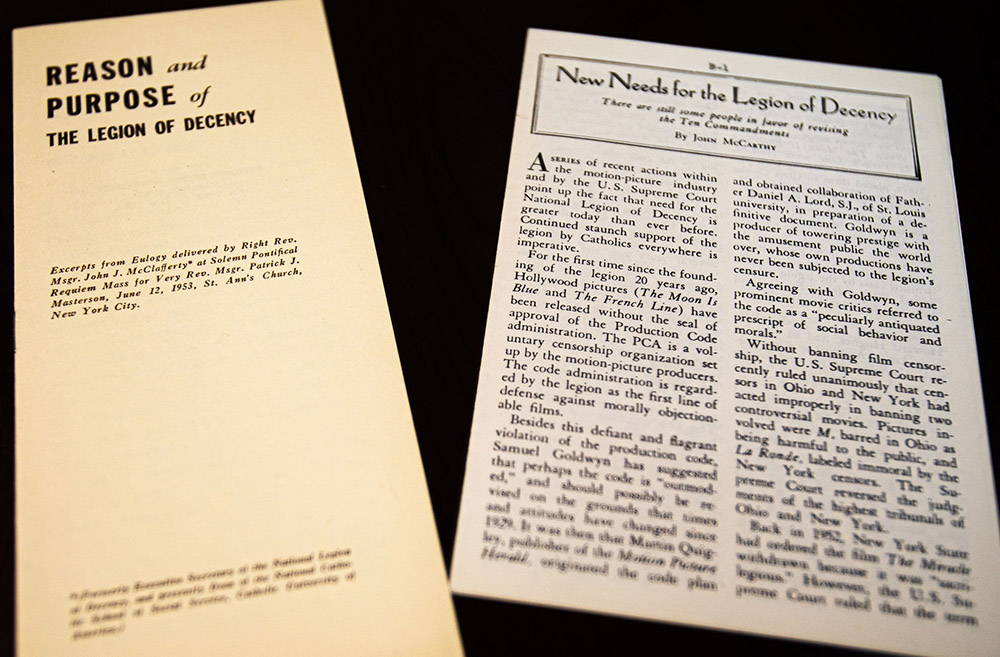

1950s-era pamphlets detail the mission of the National Legion of Decency and its role in rating films produced by the motion picture industry. (CNS/Chaz Muth)

Tony Bill is a veteran Hollywood actor, director and producer of Academy Award Best Picture "The Sting," and is also a former member of the Board of Governors of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences. Bill attended Catholic schools all his life, graduating from the University of Notre Dame.

In an interview with NCR, Bill notes that after his teen years in San Diego watching Disney flicks, "I discovered real movies ... whether Mother Church's Legion of Decency hated them or not. In fact, the opprobrium may have sweetened the experience, although frankly, I didn't pay enough attention to the sin to savor the offense."

He added: "I noted with more than normal pride and pleasure that even toward the top of several lists was one of my own productions, 'Taxi Driver.' "

Among the many condemned films are classics: "A Streetcar Named Desire," "Bonnie and Clyde" and "Midnight Cowboy" among them. Foreign films were disproportionately regarded as morally offensive, including Jean-Luc Godard's "Breathless," François Truffaut's "Jules et Jim," and Michelangelo Antonioni's first English-language film "Blowup."

Some directors did cave to the pressure from the Catholic church. President of 20th Century Fox Spyros Skouras fought the C rating over "Forever Amber" in 1947 and convinced the Legion to call off its pickets and boycott campaign by making cuts to the film. He then offered a public apology to the Legion. The new rating resulted in the movie becoming the highest grossing film of the year.

Elia Kazan cut four minutes of dialogue from "A Streetcar Named Desire" to avoid a C rating. Billy Wilder deleted scenes from the original script of "The Seven Year Itch" for the same reason.

The rating system was revised in 1978, and the designation "condemned" has not been assigned to films since. But Dougherty never revoked the ban in Philadelphia, so technically it's still a sin to go to the movies. Maybe just a venial one.