Matthew LaBanca was fired from his jobs directing a church choir and teaching music at a Catholic school in 2021, soon after he married his same-sex partner. He is starring in a one-man play he wrote about the experience called "Communion," which premieres off-Broadway Nov. 7. (Courtesy of Rebecca J. Michelson)

When Matthew LaBanca was fired by the Diocese of Brooklyn, New York, in 2021 for marrying his same-sex partner, he lost two jobs, health insurance and a cherished Catholic community.

He also received scores of messages:

"I'm in seminary and gay and don't know if I belong."

"I am in the church and closeted because I'm afraid to say anything."

"This happened to me, too."

"So many people reached out sharing their stories, asking, 'What do I do? I feel for you and I'm scared myself,' " recalled LaBanca in an interview with NCR.

There have been more than 100 instances of workers in Catholic institutions being fired, forced to resign, having offerings rescinded or having jobs threatened for LGBTQ-related reasons since 2007, according to a database managed by the LGBTQ Catholic advocacy group New Ways Ministry.

Francis DeBernardo, executive director of the Maryland-based group, said the list is not exhaustive because not all instances are made public.

The proper place and permitted behavior of LGBTQ people in the Catholic Church — from gay and lesbian employees at parishes to transgender youths in schools to gay men in the seminary — are questions that continue to rouse pain and controversy.

For many years LaBanca's work directing a parish choir and teaching music at a Catholic school had been his primary source of steady income, but he is also a skilled actor and playwright. He thought perhaps he could use storytelling to aid in his own healing and that of others who'd felt rejected by the church.

"If I could contribute to the healing of those excluded in the name of purity instead of accepted in the name of love," LaBanca said, "then it is what I wanted to do."

A new one-man play called "Communion," written and performed by the 49-year-old and premiering off-Broadway in New York City Nov. 7, is that aspiration honored.

Broadway and blackboards

LaBanca is a rarity in the New York City theater world in that he never sought gigs while waiting tables to make ends meet. Instead, he served the church he'd grown up in — teaching young children simple tunes, instructing older students in tonality and musical literacy, and cultivating community among seniors in his choir.

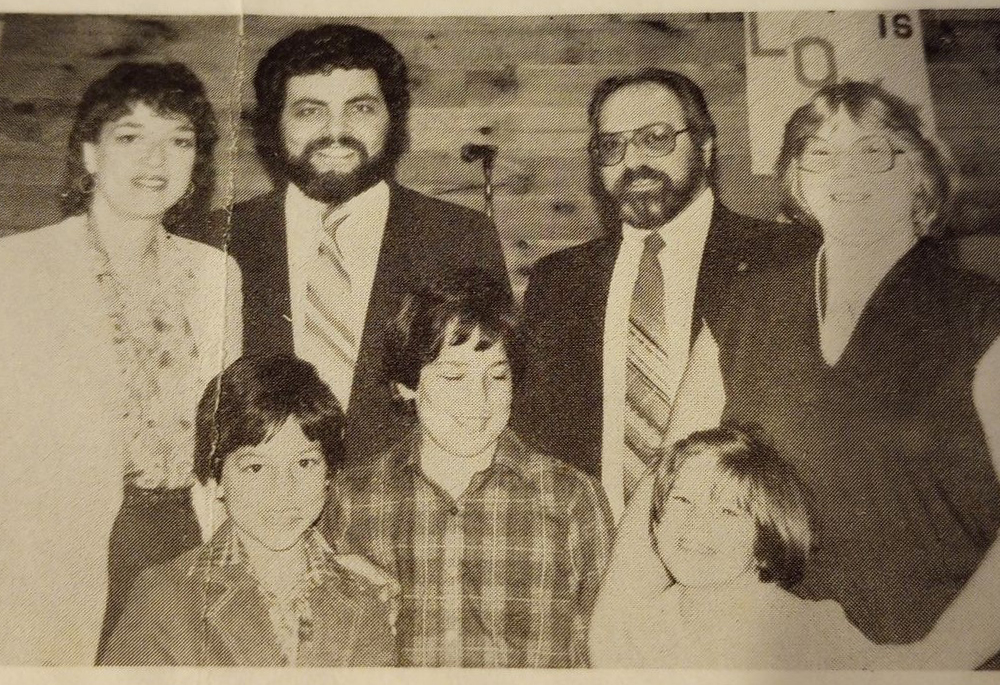

Matthew LaBanca (bottom left) is pictured in 1982 after a Sunday Mass at Sacred Heart Church in Patterson, New York, with his mom, dad, older brother and the Monaco family, all part of a folk family choir. (Courtesy of Matthew LaBanca)

"Being a performer in New York City is a difficult row to hoe, now more than ever," LaBanca said. "But I always had the option of a music educator, something I treasure."

A love and aptitude for music and performance burgeoned early in life within his tight-knit Italian Catholic family. His father was a professional magician, "a real showman," who donned a mustache and "looked just like the Monopoly man," said LaBanca, who sometimes would assist with his acts. The family was part of a folk music group, harmonizing together for "Let There Be Peace on Earth," while LaBanca, the youngest of two boys, would also belt out more traditional tunes on the organ during Mass.

A teenage Matthew LaBanca performs Christmas carols with his father, Frank LaBanca, for a local Lions Club in 1992. (Courtesy of Matthew LaBanca)

As a newly minted college graduate, LaBanca booked a national theater tour and moved to New York City. He made his Broadway debut in 2007 with Mel Brooks' "Young Frankenstein" and later performed in "Irving Berlin's White Christmas" and "A Christmas Carol."

Though his acting resume grew, his main income, insurance and daily community life were tied to a Catholic parish and school. First hired by St. Joseph Church in Queens in 2001, LaBanca served as baritone section leader for a few years. In 2005, he landed a job at Corpus Christi Church, also in Queens, as the music director, holding the post until 2007 when he left for a Broadway production and other theater opportunities. He returned to Corpus Christi in 2012 and in 2015 added the music teacher position at St. Joseph Catholic Academy.

Because LaBanca lives just blocks from the school and the parish, it was not uncommon for him to bump into current or former students.

LaBanca stars in "Backwards in High Heels" with the Arizona Theatre Company in 2010. He made his Broadway debut in 2007. (Courtesy of Matthew LaBanca)

"One of my favorite things about teaching kids, if you're lucky enough like I am, is that you get to see this potential inside them and then you see them grow up and become young adults and grow into that potential," LaBanca said. "It's a special thing to witness."

Sue Landis is a neighbor, fellow musician and friend of LaBanca who has two children at St. Joseph.

"There aren't many male teachers at the school, and Matt is a wonderful person and was a strong male figure for the kids," Landis told NCR. She recalled how he organized a recorder program for students and brought a group to Carnegie Hall to hear the orchestra and play their own recorders in the illustrious auditorium.

LaBanca said he understood he was gay in high school but that the Catholic churches he attended never made him feel that there was something wrong with him. Staff at both St. Joseph and Corpus Christi knew about his sexual orientation, he said, and were aware he was in a longtime relationship. Rowan, now his husband, was invited to choir events and attended the Mardi Gras party, bingo nights and the Christmas show.

"I wasn't overt and draping a pride flag over the piano; it wasn't anything like that for me," said LaBanca. "I wasn't hiding anything but I wasn't waving my relationship in front of people."

On Aug. 1, 2021, "the most beautiful day of my life," as LaBanca describes it in his play "Communion," he and Rowan married.

'Intrinsically disordered'

"Communion" — Scene 7

SISTER JOAN: People can sing your praises all day long, but it's one of these situations where the rules are the rules. OK? And that's it.

Scene 9

MATTHEW: What about the laws that say no one should use birth control? That no one should support abortion or the death penalty? That everyone should go to church on Sunday? Every employee meets these standards? Do you know the answer to that?

A key, given to him by the director of "Communion," dangles on a chain around LaBanca's neck. During the interview with NCR he holds it up to show it is imprinted with the word "faith."

"I think this project can instill and resurrect a sense of faith in people who might otherwise have forsaken it," he said.

Keys appear three times in the one-man play, which draws directly from LaBanca's experience with the Brooklyn Diocese. The first instance is when he receives a set for the choir room, the second is when he is fired and Deacon Tom, "the bishop's right-hand man," asks for them back.

"I gave him a decoy and kept the real ones; I wasn't ready to let go," LaBanca said.

LaBanca and Rowan married on Aug. 1, 2021. On Oct. 13, the longtime music instructor was fired from his two positions by the Diocese of Brooklyn, New York. (Courtesy of Matthew LaBanca)

LaBanca still does not know who reported concerns about his marriage to officials at the Brooklyn Diocese, an episcopate encompassing the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens. But a committee was convened to discuss his employment status, he said, and on Oct. 13, about two and a half months after his wedding, diocesan leaders told him that because he was considered a "minister" of the faith and had violated church teaching on same-sex unions, he would be asked to leave his posts.

"There was a balm during my years of work for the church in thinking that I was doing meaningful work, which I was, and in that I belonged, which I did," said LaBanca, with the final declaration expressed more like a question.

In a statement at the time of the firing, the Brooklyn Diocese said that Catholic school personnel and ministers of the church "share in the responsibility of ministering the faith to students" and must therefore "comply with church teachings."

The Catholic Church holds that LGBTQ people should be treated with respect but that same-sex sexual relationships are "intrinsically disordered."

Under federal as well as New York state and city laws it is illegal for an employer to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Yet the legal argument used by the Brooklyn Diocese and an increasing number of religious employers involves a legal doctrine known as the "ministerial exception."

In 1972 a federal appeals court recognized a constitutional right for religious entities to make employment decisions for their ministers without government regulation. The court required an exception be applied to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits employers from discriminating on the basis of race, sex and other criteria.

For decades the ministerial exception was used by the courts, however in 2012 it was explicitly recognized as a legal doctrine by the U.S. Supreme Court, whose ruling effectively broadened the scope of the exception to include not only ordained religious leaders but those deemed a minister by a church entity.

Advertisement

While there may now be more robust legal protections for firings, there also has been a decline in the annual number of LGBTQ-related employment disputes at Catholic institutions in recent years, according to New Ways Ministry.

DeBernardo, the ministry director, believes there are several reasons for the slowdown, including the papacy of Pope Francis, whose pastoral approach to LGBTQ individuals marks a distinct departure from his predecessors.

Nevertheless, firings are still relatively common. Last December the Diocese of Rockville Centre, New York, fired Michael Califano, a third grade Catholic school teacher who was in a same-sex relationship, and this May a Catholic school educator in a Seattle suburb said she lost her job because she's marrying a woman.

The wounds and division of these cases are often present years later, said DeBernardo.

For Landis, witnessing what occurred to LaBanca triggered her own crisis in faith.

Like many other Catholics, she wrestles with some church doctrines. "But I love the teachings around how we should care for one another and love one another," she said. Firing LaBanca in her view was antithetical to caring for a member of the community.

"Matt is a very good person," she said. "If he's not a good Catholic, there's no way in hell that I'm a good Catholic."

Matthew LaBanca is starring in a one-man play he wrote about his experience called "Communion," which premieres off-Broadway Nov. 7. (Courtesy of Rebecca J. Michelson)

Communion

The Brooklyn Diocese offered LaBanca a $20,000 severance package to sign a confidentiality agreement. He turned it down.

"When an LGBTQ person of faith realizes that the church they've grown up in, that's nurtured them, that's called to them, is not only labeling them as intrinsically disordered but treating them in this way, it is deeply painful," said LaBanca, his voice faltering. "I declined so that I could speak not just for myself but shine a light on what happened and the practice in the church."

With the music and humor and truth-telling in "Communion," he said, "I hope people will take away a sense of hope."

Kira Simring is director of the production and collaborated with LaBanca on his previous one-man play, "Good Enough." In a sense, Simring told NCR, she does view LaBanca as a minister. "He's an exceptional human, and that's what drew me to him," she said. Through his work "he heals, he teaches, he invites people in."

Simring said she believes "Communion" has all the elements to be successful and hopes it will eventually be brought to a wider audience. The one-man play received a developmental production last fall and in February was performed as a fundraiser for Califano, the fired third-grade teacher in Rockville Centre.

Running just over an hour, "Communion" features LaBanca portraying himself, his mother, a gay priest, the principal of St. Joseph and others. It also includes characters such as Sister Joan and Deacon Tom via audio recordings. Most characters are based on real-life individuals; some are amalgamations.

The principal of St. Joseph was an advocate for LaBanca, and there's a monologue in the play devoted to him. "He is wearing his cardigan sweater, talking about buttons the school families made for me and the kids wore on their backpacks," said LaBanca. "Each character lasts a few minutes — you encounter them and then you let them go."

LaBanca also plays the piano and glockenspiel, and the audience is treated as the choir, thereby becoming a part of the performance.

Matthew LaBanca, playing the piano in "Communion," said he thinks one of the reasons the show works well is that it is not preaching repudiation or "a reverse style of fire and brimstone against" the church. "It is a story of what happened through a human lens, through the lens of my experience — the humor and the nuance and the pain," he said. (Courtesy of Rebecca J. Michelson)

Simring said she hopes those in the audience experience a sense of communion with their fellow theatergoers.

"The individualistic priority in our culture is, I think, very harmful," she said. "I want people attending to see themselves as part of a larger whole and not just as an individual out in the world, disconnected from other people and things."

One of the reasons LaBanca said he thinks the show works so well is that it is not preaching repudiation or "a reverse style of fire and brimstone against the church."

"It is a story of what happened through a human lens, through the lens of my experience — the humor and the nuance and the pain," he said.

One acutely painful moment depicted in the play is when LaBanca, a year after being fired, walks past the church where he worked and there is a sign that reads: "Come in! This is a no-judgment zone and place of unconditional love. — Jesus"

LaBanca, who now teaches at a public school, said his faith in God has not been rocked but his faith in the institution has. These days he does not attend Mass regularly but sometimes will help out with music for a liturgy.

"I'll begin to sing and then you plug into the universal truth of it all," he said. "You're always Catholic; you have the beautiful mark on your soul, and it will always be a part of me."

At the end of "Communion," LaBanca relinquishes the key he'd been holding onto.

"I realize in the end the church isn't God; God is in the people," he said. "And they are the ones worth fighting for."

Editor's note: "Communion" premieres off-Broadway Nov. 7 and runs through Dec. 8 at Nancy Manocherian's cell theater, 338 W. 23rd St., New York City. Tickets are available at CommunionThePlay.com.