"The Cup of the Covenant" by Kateryna Haneychuk (Courtesy of Marcin Sutryk)

This summer, a Polish art critic and historian laid down a challenge to a group of contemporary icon painters from Ukraine and Poland: depict "God's justice."

Katarzyna Jakubowska-Krawczyk, head of the University of Warsaw's Institute of Ukrainian Studies, offered this charge to begin a two-week artists' retreat at a rural monastery. The artists were gathered for the annual International Iconography Workshop, a 17-year-old collaboration between Polish and Ukrainian arts organizations aimed at reviving traditional Catholic icon painting.

But in light of Russia's ongoing invasion, Jakubowska-Krawczyk and other workshop curators expanded the project's purview. They wanted not only to update devotional art but also to spark a society-wide conversation.

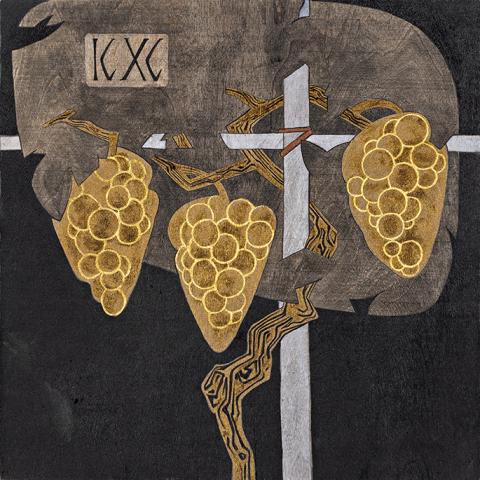

"The Vine is True" by Kateryna Haneychuk (Courtesy of Marcin Sutryk)

"Amid the daily atrocities faced by Ukrainians, questions about justice are inescapable," Jakubowska-Krawczyk told NCR.

The result was a groundbreaking exhibition, also called "God's Justice," featuring over 50 new sacred artworks. After opening in September at Lviv's Museum of Folk Architecture and Life named after Klymentiy Sheptytsky, the collection has traveled to Poland and next year will be in Germany.

Western Ukraine's tradition of icon painting is a testament to the region's role as a cultural and religious crossroads. Western Ukraine's Greek Catholics, who use Eastern Orthodox-style worship but also belong to the global Catholic Church, often use icons in worship and prayer. Lviv's connections to the Latin-rite Catholic Church date back to the period before World War II when the city was part of Poland.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Ukraine experienced a religious revival. In 2005, Lviv's Ukrainian Catholic University founded a sacred arts program, the Radruzh Iconography School, to train artists to restore church buildings that had been abandoned or used for secular purposes under communism.

"Protection" by Natalya Satsyk (Courtesy of Marcin Sutryk)

Today, the International Iconography Workshop helps the broader church learn about Ukraine's Greek Catholic traditions. Graduates of the Radruzh Iconography School also exhibit their work at ICONART Gallery, a contemporary art space in Lviv whose owners are also workshop curators. ICONART continues to show work by participants in this year's "God's Justice" exhibition, including young icon artists Olya Kravchenko (37, from Lviv), Albina Yaloza (46, from Kharkiv), and Roman Zilinko (45, from Ternopil).

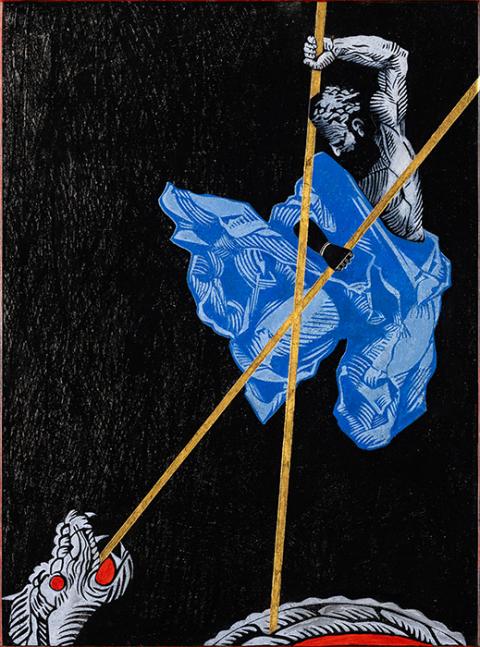

"Warrior" by Albina Yaloza (Courtesy of Marcin Sutryk)

Contemporary icon painters, according to theologian Fr. Grzegorz Michalczyk's essay in the exhibition catalogue, intervene at the limits of the church's liturgy. Michalczyk, a diocesan priest in Warsaw and chaplain to the artistic community, says that Psalm 109, for example, gives voice to a powerful but natural desire for vengeance. However, the version used in the liturgy does not include these images. When the liturgy does not have the courage to confront ugly yet natural human impulses, Michalczyk writes, art can provide a cultural space for people to ponder how we should respond ethically to our own suffering.

Many artists responded to the workshop prompt by portraying the Archangel Michael with scales in one hand and sword in another. Others also portrayed St. George slaying the dragon, showing how Christian heroes defended themselves against an alien and seemingly undefeatable occupier.

"Who is like God" by Albina Yaloza (Courtesy of Marcin Sutryk)

Yaloza's "Who is Like God," is a linocut print produced in black-and-white, except for the flaming ochre of the central figure's hair. This man's over-the-top brawn and his impossibly sharp forehead and nose are hallmarks of Yaloza's comic book-inspired aesthetic. Like Archangel Michael, the man grasps a sword and seems ready to plunge it downward into an unknown, unseen foe outside the icon's frame.

For Yaloza, the question "Who is Like God" recalls the Deuteronomistic injunction, "Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord." The eternally other God has claimed revenge as God's own. The etched feather design framing the central figure suggests he's an angel. But this avenging figure could still be human? We don't actually see if the feathers are attached to his shoulders.

Advertisement

Many of the artists in "God's Justice" use natural media and "naive" imagery. Kateryna Haneychuk used acrylic on a rough-hewn board to portray a full chalice. Straight lines cut across the vessel in the foreground. There are items associated with the crucifixion: thorns, nails, even a ladder. But they also look like missiles, bullets and the other tools of industrialized warfare. The perspective is flat, evoking not only the traditional aesthetic of Eastern iconography but also how violence erases psychological depth from human experience.

Many artists were preoccupied by the horror of Russia's July 2024 missile attack on a Kyiv children's hospital. Images of Mary with child are repeated throughout the exhibit, but the portrayals refuse sentimentality. Natalya Satsyk's "Solicitude," plants a pregnant Mary's legs into a flat landscape, but the soil is dry and barren like charcoal.

"Incarnation of God" by Natalya Satsyk (Courtesy of Marcin Sutryk)

The icons testify to the unfolding tragedy in Ukraine, as well as losses both personal and collective. Artists in Ukraine's historical Catholic heartland are confronting the rising anger in their own society not only by healing the psychic wounds of war, but also by calling the faithful to a deeper conversation about how to sustain faith amid widespread suffering.

But the International Iconography Workshop also testifies to the friendships and institutional partnerships that tie Ukrainians with their neighbors in Poland. The exhibitions, according to Jakubowska-Krawczyk, are merely the final fruits of friendship as well as mutual empathy and support that transcends denominational and national boundaries.