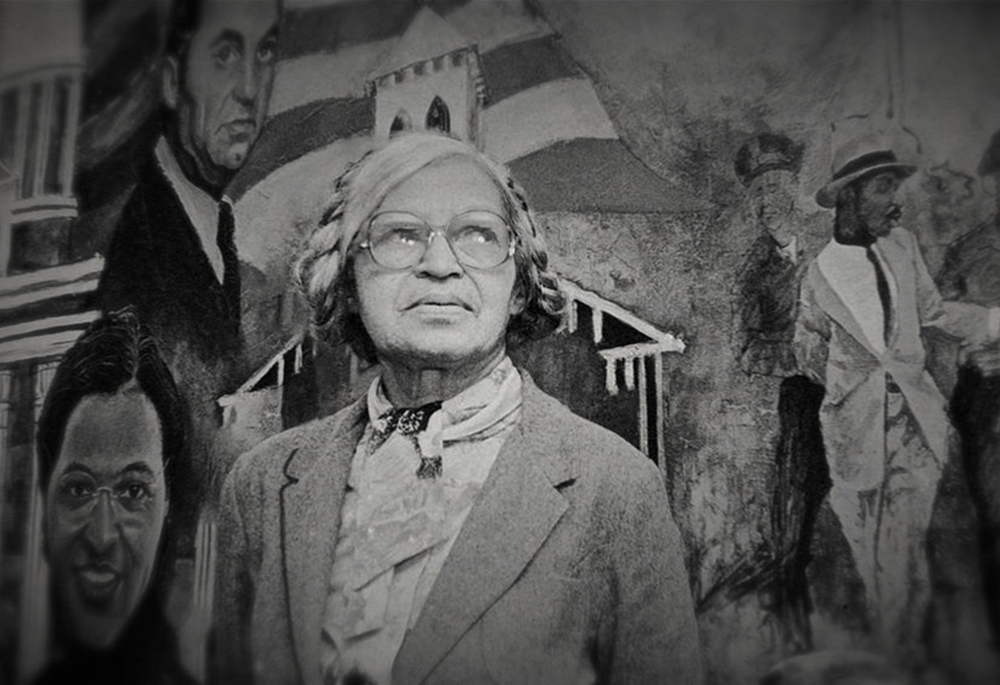

Rosa Parks is pictured in this photo. "The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks" asserts that her refusal to cede her seat to a white man on a city bus in 1955 was not a spontaneous act, but an intentional choice rooted in two decades of activism. (Courtesy of Peacock)

"She was the quietest participant in the workshop but we had high hopes for her," Myles Horton, founder of the Highlander Folk School says in a new documentary about Rosa Parks, who attended a training on desegregation in Monteagle, Tennessee, in the summer of 1955.

"The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks" makes plain: this education prepared Parks not to cede her seat to a white man on a Montgomery, Alabama, city bus on Dec. 1, 1955. It wasn't the spontaneous act of a 42-year-old seamstress tired after a long day. Rather, rooted in two decades of activism, Parks' choice was intentional.

Unfortunately, "The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks" has miscalculations with its narrative and a tendency to regard its subject uncritically, which undermines the documentary's commendable designs.

Johanna Hamilton ("1971," 2014) and Yoruba Richen ("The Sit-In: Harry Belafonte Hosts The Tonight Show," 2020) direct and executive produce the film. Veteran television journalist Soledad O'Brien also executive produces. The documentary shares its tile with Jeanne Theoharis' acclaimed 2013 biography.

The documentarians also take advantage of a trove of Parks' letters, photos and artifacts that were made public in December 2019. The Library of Congress' exhibition: "Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words" is well worth exploring.

Actress LisaGay Hamilton ("The Practice") reads the protagonist's words, enhancing the archival clips of Parks' interviews and speeches.

As Richen did in "The Sit-In," the filmmakers employ a pop culture moment to connect viewers to a social justice narrative and introduce their audience to Parks. In a 1980 "To Tell the Truth" episode, Parks appears alongside two imposters as panelists attempt to ascertain who the real Rosa Parks is.

The late Black comic Nipsey Russell disqualifies himself because he met Parks when they were at the march for voting rights in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965. "Miss Rosa Parks is 10 feet tall," the entertainer said, "and she's a legend and a hero in the democracy in the United States."

But by remembering Parks for one fateful decision 77 years ago, in the filmmakers' proper judgment, we don't serve her legacy well. They remind us Parks was an activist before and after she kept her bus seat.

The filmmakers trace the early influences that shaped the leader's activism. Born Rosa McCauley on Feb. 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Alabama, she recalls her grandfather keeping a gun close during a period of Ku Klux Klan resurgence when they perceived Black soldiers returning home from World War I as threats.

Parks also remembers an incident where a white boy was taunting her and her younger brother Sylvester, and she picked up a brick to hit the white boy but thought better of it. Her great nephew, Lonnie McCauley, says she was "a soldier from birth and she was going to fight you."

The lessons she learned at Miss White's Montgomery Industrial School for Girls in Montgomery, Alabama, also abided with Parks. Her father, James, was absent, and her mother Leona sent her to the private school when she was 11 because public school after sixth grade wasn't an option for Black Alabamians then.

Her teachers were white women who "adhered to the philosophy of industrial education and the domestic arts most prominently espoused by Booker T. Washington," Theoharis writes.

There, the activist discovered she was "a person with dignity and self-respect. I should not set my sights lower than anybody else just because I was Black."

Advertisement

Montgomery barber Raymond Parks was "the first real activist I ever met," Parks said. The couple married in 1932. Raymond's commitment to the Scottsboro Boys — nine Black men falsely accused in 1931 of raping two white women in Scottsboro, Alabama — impressed Parks and informed her involvement with Alabama's NAACP.

This quotation reflects the activist's mindset at the time of her storied protest: "Treading the tight-rope of Jim Crow from birth to death … from the cradle to the grave is a major mental acrobatic feat. It takes a noble soul to plumb this line," she said.

Parks' arrest precipitated the Montgomery bus boycott, which the Women's Political Council chiefly organized. It led to the Montgomery Improvement Association's formation and Dexter Avenue Baptist Church's 26-year-old new pastor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s emergence as a civil rights leader.

Blacks organized a carpool that offered 10,000-15,000 rides daily. White resistance was fierce. Car tires were slashed and the homes of movement leaders King and NAACP leader E.D. Nixon were bombed.

But protesters also received financial donations, which were used to purchase station wagons. Parks was a defendant in the state case seeking to end segregation on the buses. But dropping her as a plaintiff because of her activism, her attorney, Medal of Freedom recipient Fred Gray, filed a federal case. The Supreme Court decision in Browder v. Gayle affirmed the Alabama District Court's decision ending bus segregation.

Ending Dec. 20, 1956, the boycott "was the most successful boycott in U.S. history," Highlander Center co-executive director Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson says in the documentary.

Rosa Parks (Courtesy of Peacock)

The boycott exacted a great toll upon Parks and her family. She lost her lost job as an assistant tailor at Montgomery Fair department store, and Raymond quit his at Maxwell Air Force Base because he couldn't discuss his wife's case. Struggling financially and facing constant death threats, the family moved in 1957 to Detroit where Sylvester lived.

The filmmakers' description of her meeting with Malcolm X in the city the week prior to his Feb. 21, 1965, assassination underscores what the documentarians want us to take away from their film. "Dr. King believed Black people should receive brutality with love," Parks said, "and I believed this was a goal to work for but I could not reach that point in my mind at all. Malcolm wasn't a supporter of nonviolence either."

Parks' embrace of self-defense explains, the filmmakers believe, her support of the revolutionary Black Liberation movement Republic of New Afrika (or RNA). Co-founded in Detroit in 1971 by Imari Obadele, some of the group's aims were relatable: reparations for slavery and Jim Crow, but their desire for a Black state in the South may seem too extreme to some.

The group more controversially was also involved in shootouts with police in Jackson, Mississippi, and Detroit in which police officers died. Those who, like the late John Lewis, still believe "nonviolence is the more excellent way" will be troubled by Parks' dubious association with the RNA.

Viewers will also wonder why this material was introduced early in the film before we have a more complete picture of what motivated the activist and the bus boycott story is told.

"The Rebellious Life" isn't a poorly made film. The directors make good use of archival video and Parks' words to shape the narrative. Their thesis about not limiting their subject to one momentous episode is rock solid, moreover. By emphasizing the peripheral over the central, and not acknowledging the controversial, however, they risk alienating viewers gratuitously.

"The Rebellious Life" would have worked better if the filmmakers trusted us: to balance our criticism with our admiration without losing sight of our profound gratitude for what Rosa Parks did to free us.