Matthew Goode as C.S. Lewis (left) and Anthony Hopkins as Sigmund Freud in the film "Freud’s Last Session" (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics/Sabrina Lantos)

Conversation is a gift. Or it can be, if we approach it with the right disposition. After all, what is a conversation? We're saying to another, "I want to hear you. I want to give you my attention, my time. I want to accompany you in this moment. And I want you to accompany me."

But for me, at least, conversation often falls far short of such a lofty ideal. I rush to offer my thoughts, to move onto the next idea, next person, next shiny object. My attention wanders and rather than accompany the other, I suddenly find that I've left them all alone in the proverbial wilderness. I imagine I'm not the only one.

"Freud's Last Session," the 2023 film directed by Matthew Brown, is a meditation on conversation, and a difficult one at that. The movie is based on Mark St. Germain's 2009 play by the same name, which in turn was influenced by Armand Nicholi's 2003 book, The Question of God: C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Debate God, Love, Sex, and the Meaning of Life.

In the film, Anthony Hopkins stars as the legendary psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud alongside Matthew Goode as the renowned writer and Christian apologist C.S. Lewis. The two meet in Freud's London home to discuss God, humanity and the intermingling of the two.

It's a conversation with existential stakes, only further highlighted by the fact that this fictional story takes place in the earliest days of World War II. What role could an all-loving God possibly play in a world torn asunder?

Advertisement

I'm drawn to films like this one, stories that center on conversation. I'm reminded of "The Journey" (2016), in which Northern Irish leaders Martin McGuinness (Colm Meaney) and Ian Paisley (Timothy Spall) are forced into uncomfortable conversation about the future of peace in their land. I'm brought back to "The Two Popes" (2019), in which Pope Benedict XVI (Anthony Hopkins) and then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio (Jonathan Pryce) discuss different possibilities for the future of the Catholic Church.

In these two films, as in "Freud's Last Session," the viewer sits as a silent observer, witnessing larger-than-life characters from history and culture collide by way of opposing ideologies. And since these figures are already so well enmeshed in the cultural zeitgeist, the filmmaker can spend less time on character development and more on dialogue. We're here for the conversation; we already know upon which side of the debate Freud and Lewis fall.

But here, too, is a storytelling temptation: How to avoid reducing Freud and Lewis to mere caricatures of themselves? In this way, "Freud's Last Session" struggles.

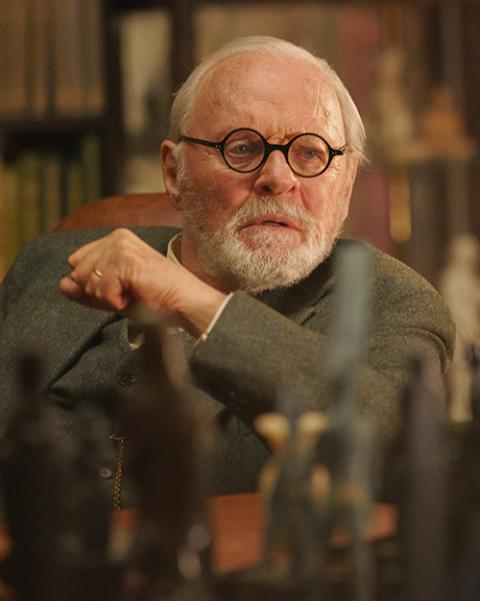

Anthony Hopkins as Sigmund Freud in "Freud’s Last Session" (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics/Sabrina Lantos)

We get glimpses of backstory for both Freud and Lewis, insights into important relationships in their lives, but these are no more than glimmers. I found myself too often googling details of both men's biographies in an effort to separate fact from fiction.

These brief images of their pasts did little more than reinforce what we already know: Both men are flawed and struggling and yet still persist along their decided paths.

Their conversation persists, too, though in starts and stops. Lewis arrives at Freud's home late, having given up his place on the train in order to accommodate children fleeing the war. And Freud is unhappy with Lewis' tardiness. The great Dr. Freud, after all, doesn't have all day!

And yet, he seems to. I found myself distracted by the fact that Lewis lingers around Freud's home well past the socially acceptable hour, even though both men seem resolute in cutting their conversation short. As a result, the conversation never really picks up.

Each man lobs at the other talking points that seem obvious: How can you believe in a loving God when we suffer as we do? How can you not believe in a God when so many of our human desires seem to have no natural fulfillment? And so on.

Still. Hopkins and Goode give masterful performances that transcend the conversation at hand. Because while they banter back and forth about morality and sex and relationships and disorders, what they're really talking about is fear — fear of the unknown, fear of their own necessary limitations, fear of the impending darkness. And while the dialogue may fall flat at times, the heart of their conversation pulls us in.

While they banter back and forth about morality and sex and relationships and disorders, what they're really talking about is fear.

Early on in the film, sirens blare, warning of impending bombs. The younger Lewis — still hardly acquainted with his host — helps the old and ailing Freud hobble to the shelter, pulling on his gas mask along the way. Lewis refuses to leave him behind, though Freud insists he should.

Once in the shelter, Lewis begins to have flashbacks to his time in World War I, evidence of his post-traumatic stress disorder. He begins to hyperventilate. Dr. Freud grabs the younger man, looks him in the eye and tells him to breathe, reminding him where he is, that he's OK. And it works.

This scene struck me because, at that point in the film, the two men are little more than caricatures to even each other. They knew one another no more than they knew the other souls trapped in that shelter with them. But Lewis, true to his Christian beliefs, refused to leave a vulnerable person behind, and Freud, the doctor that he was, used his skill for the good of the man in front of him — even if he didn't share that person's beliefs.

Matthew Goode as C.S. Lewis in "Freud’s Last Session" (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics/Sabrina Lantos)

And so, as Lewis lingers in Freud's home, witnessing the doctor's slow decline from oral cancer, he can't help but care for him. He walks his dog and retrieves fresh handkerchiefs. He accompanies the doctor — and Freud allows it. Despite the clear defenses around so much of his life, in this simple, quiet moment when the world was at war, Freud allows Lewis in.

A true conversation. A turning to the other. A poignant sense of accompaniment. Neither man was convinced of the other's point of view, but that didn't really matter.

The film succeeded in reminding us of our shared humanity, that no matter how many degrees we might possess or how many books we've published, we all grapple with that impending darkness, with fear of our necessary limitations and decline.

The world of "Freud's Last Session" is not so different from the world in which we find ourselves, one marked by war, conflict, chaos.

In such a world, it's tempting to think that our own little problems, little questions, little conversations have no place, that they don't matter against such a catastrophic backdrop. But the lesson of "Freud's Last Session" is that they do — it is precisely in these moments when such conversations are most important.

They might lead us to another — a friend, a companion — who can accompany us along the way. And for those of us who happen to fall on Professor Lewis' side of the argument, we might even say that it is through those conversations, through those people who dare to walk with us in our own darkness, that we glimpse that all-loving, if at times elusive, God.