Panoramic view of the Bogside murals in Derry, Northern Ireland (Mary Ann Cejka)

Across Rossville Street from the once notorious Bogside neighborhood in Derry (Northern Ireland's second largest city — also known as Londonderry) is a new, brightly painted Spaghetti Junction, catering to the expanding palates of the area's residents. Upstairs from the tanning salon in a recently renovated building a few feet away, trendy urban-chic apartments are for rent. Those who can afford them will have views of the now well-touristed Bogside murals.

The murals serve as a reminder of the contrast between past and present. Less sanguinely, they also call attention to the ominous possibility that the past may not be wholly past.

In the latter decades of the 20th century, the "Troubles" — a simmering and sporadically explosive conflict that pitted Irish nationalists against unionists, republicans against loyalists, Catholics against Protestants — ultimately claimed more than 3,600 lives. Masked and gun-wielding paramilitaries, armored cars, tanks, burning tires, petrol bombs, and attacks on funeral-goers kept much of the country in a state of terror. Meanwhile, murals on both sides of the conflict served several purposes: to spread news, record events, instill sectarian or partisan identity (marking out territory in the process), recruit new paramilitary warriors and intimidate.

Unionist murals first appeared in 1908; mural-painting then waned, waxed and waned again over the next several decades. In 1981, a hunger strike that led to the deaths of 10 republican prisoners inspired a resurgence of murals in the prisoners' protesting neighborhoods, eventually followed by a comparable proliferation of murals in loyalist areas.

While both sides favored images of hooded men with guns, the republican side drew on a broader array of themes: Celtic mythology, Irish history (including the Great Famine) and solidarity with contemporary resistance movements in other parts of the world. Some republican murals have depicted Celtic crosses, Catholic cathedrals, notable priests or shamrocks, but murals in the predominantly Catholic neighborhoods were, and still are, more reflective of nationalist, republican and socialist ideals than of religious sensibilities. Unionist murals of the same period frequently depicted the Red Hand of Ulster (the symbo of the province) and the ubiquitous "No surrender!" slogan.

After the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 mandated decommissioning of weapons and early release of prisoners for both factions, republicans limited gun depictions to murals with historical or commemorative themes. Loyalist murals, in contrast, became more belligerent, perhaps because their communities had less to gain from peace than did republicans; or, as sociologist John Brewer observed, because Northern Ireland Protestant "theological positions on the notion of sin and forgiveness" caused loyalists to regard true repentance on the part of republican militants as unlikely.

Advertisement

Trouble after the 'Troubles'

The Good Friday Agreement established structures to enable participation of both unionists and Irish nationalists in the country's governance. But at no point since that agreement has it been possible for the people of Northern Ireland to rest easy in the assurance of an ongoing and sustainable peace. Several factors have conspired to postpone the realization of this goal — simple and obvious in its necessity, yet relentlessly elusive in its attainment — including:

• Parades, bonfires, effigy burnings and occasional eruptions of sectarian violence that keep tensions alive;

• Government failure to investigate some of the killings that occurred during the Troubles, so that many believed to be perpetrators have never been brought to justice;

• The rise of some such perpetrators to positions of power, and a culture of silence enshrouding these developments, leaving many victims and their families to despair of ever receiving compensation or seeing the historical record set straight;

• The decline of traditional industry, and the failure of the "peace dividend" to benefit those whose livelihoods rely upon manufacturing jobs;

• Ongoing social deprivation in these communities, with 16 of the 20 poorest being predominantly Catholic-nationalist;

• Ongoing segregation of schools and neighborhoods, with cross-the-divide friendships still relatively rare;

• The January 2017 collapse of the power-sharing (between both unionists and nationalists) government with the potential for a return to direct British rule;

• The possible loss, due to Brexit, of millions of dollars in peace funding allocated by the European Union in the form of "reconciliation grants";

• Also due to Brexit, the possible reintroduction of a hard border — even, perhaps, a border wall — between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland;

• The $1.3 billion deal reached this summer between embattled British Prime Minister Theresa May with Northern Ireland's most powerful unionist party to bolster her conservative minority government. The agreement could undo any trust the British government had gained among nationalists as an impartial actor in Northern Ireland's peace process.

Yet, even as former British Prime Minister John Major warned of the destabilizing potential of May's deal with the unionists, he also noted the "broad consensus" that Northern Ireland's hard-won peace must continue. Local religious leaders representing the Catholic and mainline Protestant churches, as well as some from other faith traditions, have frequently and often jointly responded to contentious issues by calling for their peaceful resolution.

A sampling of the Bogside murals in Derry, Northern Ireland (Mary Ann Cejka)

In February, the country's Catholic bishops issued a statement reaffirming the church's commitment to serving as a voice for reconciliation and the preservation of peace. That peace, meanwhile, has survived thus far in part by helping to attract billions of dollars in foreign investments to Northern Ireland, largely in technology, filmmaking and tourism.

Belfast, Northern Ireland's capital and its largest city, boasts a thriving culinary scene and glittering waterfront. Taxis take out-of-town vacationers on "bombs and bullets" tours to view the city's republican and loyalist murals. The Titanic Belfast Centre, the shipyard that built the doomed ocean liner, is a major tourist draw. Even as a "we are not amused" statue of Queen Victoria stands at the entrance to City Hall, the city itself is a decidedly bright, non-dour jewel of Victorian architecture.

Take a late afternoon train — clean, efficient, and Wi-Fi-equipped, by the way — from Belfast Central Station to Derry, and upon your arrival, you'll gaze across the River Foyle at the beckoning Peace Bridge and cityscape settling into gentle evening shadows as the sun sinks behind the Donegal hills (located in the Republic of Ireland) on the horizon. Derry is a beautiful and energetic city; new construction seems to be underway everywhere, even as the city's agonized past is well honored. Pedestrians stroll unhurriedly atop Derry's intact 17th-century city wall, descending at intervals to visit ancient churches, stylish shops, cafés and art galleries. In 2013, the United Kingdom recognized Derry as its City of Culture for the year.

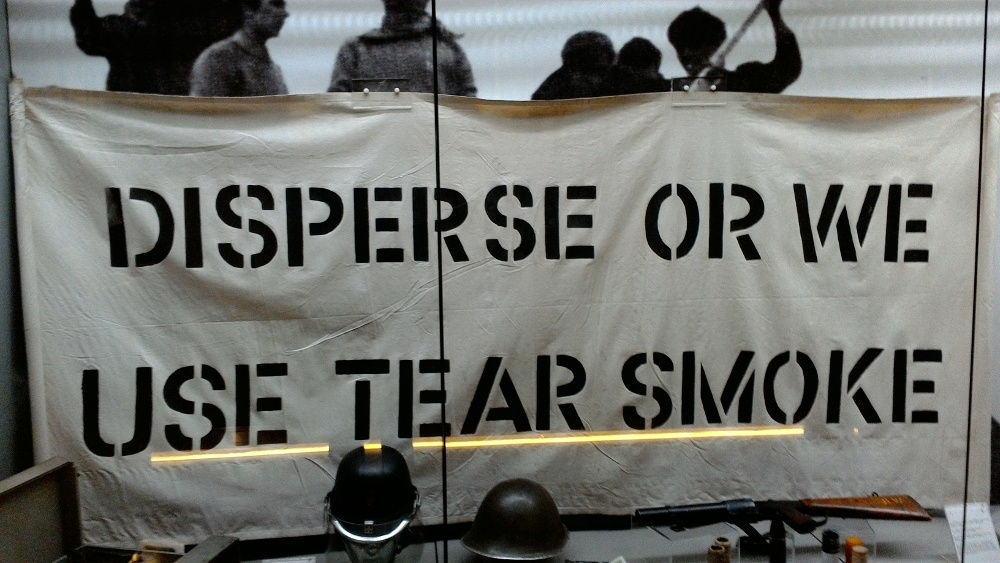

In Bogside, the small but proud Museum of Free Derry, opened in 2007 and recently re-located to a new, state-of-the-art facility, chronicles the history of the neighborhood itself and of the Troubles more broadly. Located near the site of the 1972 Bloody Sunday massacre, when 13 Bogside marchers were killed in a peaceful civil rights demonstration (another died months later), the museum now attracts visitors from both nationalist and unionist communities. Its very existence — as a history museum — suggests the neighborhood's ability to put some psychological distance between past and present, even as the museum promotes an ongoing justice campaign for truth-telling and redress of grievances perpetrated during the Troubles.

Exhibits at the Museum of Free Derry (Mary Ann Cejka)

New faces, new culture?

In the end, though, it may be Northern Ireland's emerging demographics that will relegate its violent past to the archives of history. Catholics are less in the minority than they once were; a 2011 census revealed that they now constitute 45 percent of the population, as compared to the 48 percent Protestant majority.

Catholics' steadily greater representation has translated to gradual, if not universal, gains in their collective access to education, wealth and influence. These gains, in turn, have had the effect of reducing collective frustration and of dampening motivation to engage in provocative acts.

The census also revealed that about 10 percent of the people in Northern Ireland are immigrants. They come from many countries: Romania, South Africa, the Philippines, Morocco, Indonesia, Pakistan, Lithuania, Poland and Portugal among them. The immigrants drive buses, open barber shops and restaurants, and take their children fishing in the abundant loughs. They have little interest in the sectarian divides that have preoccupied the communities. Indeed, those divides and the conflict they can still engender are nothing compared to what many of the immigrants have left behind.

The faces of these newer arrivals are beginning to appear in contemporary murals. The images of gunmen in paramilitary regalia have had to make room for depictions of community pride in diversity and in their local athletes. Schoolchildren are designing and painting murals of scenes promoting tolerance and peace. On Rossville Street, more seasoned artists have added the portraits of Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King Jr. and Mother Teresa of Kolkata, with a bridge (oddly enough, it's that rather famous one connecting Brooklyn with Manhattan in New York City) inserted to symbolize their heroic lives as builders of bridges between disparate groups.

As for the loyalist neighborhoods: Murals in homage to paramilitaries are increasingly giving way to less controversial, historical scenes, such as portraits of William of Orange or depictions of Ulster forces fighting in World War I (a sign of Protestant loyalty to the British crown).

On both sides, a long-standing tradition of not defacing the other's murals, and leaving them graffiti-free, still holds. Some murals have been jointly painted by republican and loyalist artists. Between 2006 and 2015, a "Re-imaging Communities Programme" (later known as "Building Peace through the Arts: Re-imaging Communities"), funded primarily by various mediating organizations, the International Fund for Ireland, and the European Union, supported arts projects promoting "tolerance and understanding" and "a shared future." Murals that were once used to divide communities have instead been helping to connect them. Concerns soon surfaced that the new murals would "whitewash" the Troubles, but in today's mixed economy of mural painting, both history and hope are depicted.

If peace in Northern Ireland has been hard-won, it is now not only showing its worth for the country's established communities, but also opening doors to immigrants. In an unexpectedly blessed cycle of consequences, the newcomers, their cultures and their dreams for the future are, in turn, opening doors to peace. May future murals, if murals there be, help to keep the dreams alive and the doors wide open.

[Mary Ann Cejka directed a Maryknoll-sponsored study of grassroots peacemaking that included Northern Ireland. She teaches graduate courses for Walden University and Global Ministries University.]